A new working paper confirms what economists have been saying about tariffs all along:

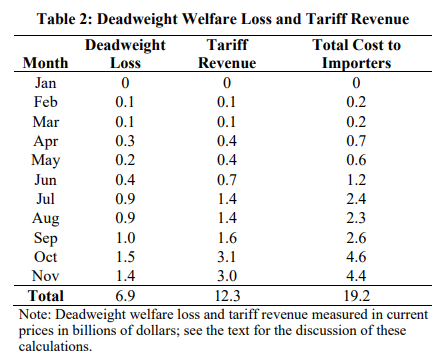

Economists have long argued that there are real income losses from import protection. Using the evidence to date from the 2018 trade war, we find empirical support for these arguments. We estimate the cumulative deadweight welfare cost (reduction in real income) from the U.S. tariffs to be around $6.9 billion during the first 11 months of 2018, with an additional cost of $12.3 billion to domestic consumers and importers in the form of tariff revenue transferred to the government. The deadweight welfare costs alone reached $1.4 billion per month by November of 2018. The trade war also caused dramatic adjustments in international supply chains, as approximately $165 billion dollars of trade ($136 billion of imports and $29 billion of exports) is lost or redirected in order to avoid the tariffs. We find that the U.S. tariffs were almost completely passed through into U.S. domestic prices, so that the entire incidence of the tariffs fell on domestic consumers and importers up to now, with no impact so far on the prices received by foreign exporters. We also find that U.S. producers responded to reduced import competition by raising their prices.

Our estimates, while concerning, omit other potentially large costs such as policy uncertainty as emphasized by Handley and Limão (2017) and Pierce and Schott (2016). While these effects of greater trade policy uncertainty are beyond the scope of this study, they are likely to be considerable, and may be reflected in the substantial falls in U.S. and Chinese equity markets around the time of some of the most important trade policy announcements (pg. 22-23).