From a new working paper:

The empirical evidence comes down decidedly on the side of immigrants being less likely to commit crimes. A large body of empirical research concludes that immigrants are less likely than similar US natives to commit crimes, and the incarceration rate is lower among the foreign-born than among the native-born (see, for example, Butcher and Piehl 1998a, 1998b, 2007; Hagan and Palloni 1999; Rumbaut et al. 2006). Among men ages 18 to 39—prime ages for engaging in criminal behavior—the incarceration rate among immigrants is one-fourth the rate among US natives (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2015).

…There is some evidence that the lower propensity of immigrants to commit crimes does not carry over to immigrants’ children. The US-born children of immigrants—often called the “second generation”— appear to engage in criminal behavior at rates similar to other US natives (Bersani 2014a, 2014b). This 4 “downward assimilation” may be surprising, since the second generation tends to considerably outperform their immigrant parents in terms of education and labor-market outcomes and therefore might be expected to have even lower rates of criminal behavior (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2015). Instead, immigrants’ children are much like their peers in terms of criminal behavior. This evidence mirrors findings that the immigrant advantage over US natives in terms of health tends to not carry over to the second generation (e.g., Acevedo-Garcia et al. 2010).

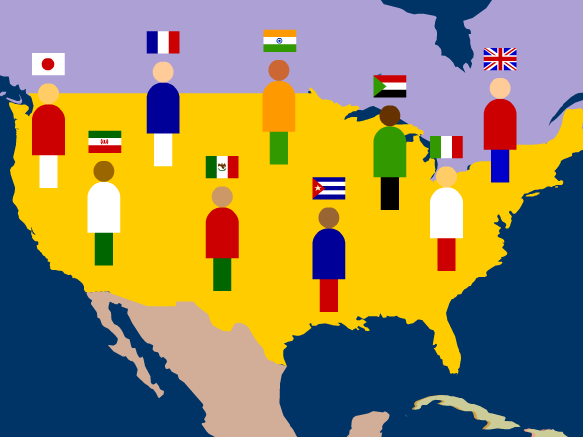

Although immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than similar US natives, they are disproportionately male and relatively young—characteristics associated with crime. Does this difference in demographic composition mean that the average immigrant is more likely than the average US native to commit crimes? Studies comparing immigrants’ and US natives’ criminal behavior and incarceration rates tend to focus on relatively young men, leaving the broader question unanswered. However, indirect evidence is available from looking at the relationship between immigration and crime rates. If the average immigrant is more likely than the average US native to commit crimes, areas with more immigrants should have higher crime rates than areas with fewer immigrants. The evidence here is clear: crime rates are no higher, and are perhaps lower, in areas with more immigrants. An extensive body of research examines how changes in the foreign-born share of the population affect changes in crime rates. Focusing on changes allows researchers to control for unobservable differences across areas. The finding of either a null relationship or a small negative relationship holds in raw comparisons, in studies that control for other variables that could underlie the results from raw comparisons, and in studies that use instrumental variables to identify immigrant inflows that are independent of factors that also affect crime rates, such as underlying economic conditions (see, for example, Butcher and Piehl 1998b; Lee, Martinez, and Rosenfeld 2001; Reid et al. 2005; Graif and Sampson 2009; Ousey and Kubrin 2009; Stowell et al. 2009; Wadsworth 2010; MacDonald, Hipp, and Gill 2013; Adelman et al. 2017). The lack of a positive relationship is generally robust to using different measures of immigration, looking at different types of crimes, and examining different geographic levels.2 Further, the lack of a positive relationship suggests that immigration does not cause US natives to commit more crimes. This might occur if immigration worsens natives’ labor market opportunities, for example.

The few studies that examine crime among unauthorized immigrants have findings that are consistent with the broader pattern among immigrants—namely, unauthorized immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than similar US natives (apart from immigration-related offenses).4 Likewise, studies that examine the link between the estimated number of unauthorized immigrants as a share of an area’s population and crime rates in that area typically find evidence of null or negative effects (pg. 3-5).

Comparatively, the effects of border control on crime is mixed. The authors conclude,

A crucial fact seems to have been forgotten by some policy makers as they have ramped up immigration enforcement over the last two decades: immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than similar US natives. This is not to say that immigrants never commit crimes. But the evidence is clear that they are not more likely to do so than US natives. The comprehensive 2015 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on immigration integration concludes that the finding that immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than US natives “seems to apply to all racial and ethnic groups of immigrants, as well as applying over different decades and across varying historical contexts” (328). Unauthorized immigrants may be slightly more likely than legal immigrants to commit crimes, but they are still less likely than their US-born peers to do so. Further, areas with more immigrants tend to have lower rates of violent and property crimes. In the face of such evidence, policies aimed at reducing the number of immigrants, including unauthorized immigrants, seem unlikely to reduce crime and increase public safety (pg. 11).