From my paper in Economic Affairs:

The…act of seeking out mutually beneficial exchanges with others expands what Michael Shermer (2015) calls the ‘moral sphere’. As this sphere diversifies, our attitudes regarding the vulnerable and disenfranchised tend to alter for the better. This moral expansion is likely why economic globalisation has been linked to fewer governmental violations of human rights, namely torture, extrajudicial killings, political imprisonment, and disappearances (De Soysa and Vadlammanati 2011). An analysis of 117 countries between 1981 and 2006 also found ‘positive effects of market-economic policy reforms on government respect for human rights’ (De Soysa and Vadlammanati 2013, p. 180) as defined above. While these studies seem to imply the market’s influence on human rights, there is also evidence that human rights boost market liberalisation. Utilising the CIRI Human Rights Data Project (which reports on extrajudicial killings, disappearances, torture, political imprisonment, freedom of speech and government censorship, freedom of religion, freedom of movement and migration, freedom of assembly and association, free and fair elections, workers’ rights, and women’s rights), a 2010 study finds that human rights abuses ‘actually reduce the pace of economic liberalization’ (Carden and Lawson 2010, p. 12). These studies seem to confirm that morals and markets create a positive feedback loop regarding human rights.

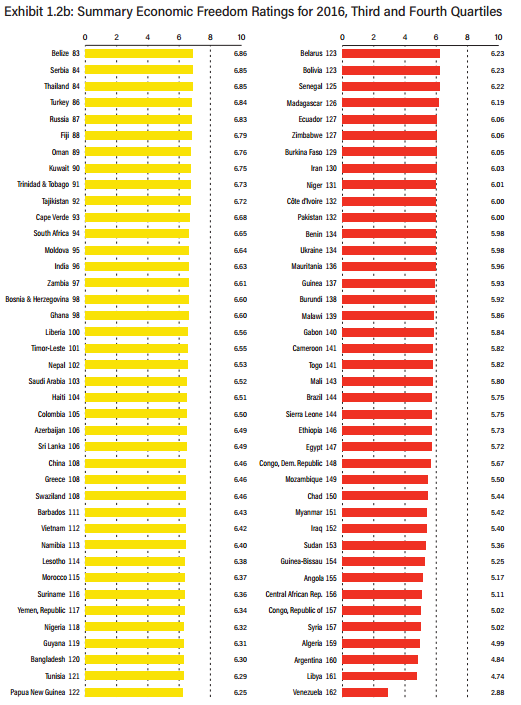

…[T]rade and business openness largely reduces the incentives of war and brutalisation. People become more valuable alive and able as potential partners, lenders, investors, and customers…After analysing data spanning from 1970 to 2005, De Soysa and Fjelde (2010) find that higher economic freedom lowers the risk of civil war, more so even than democracy and good governance. This remains true after variables such as income per capita, growth rates, total population, ethnic fractionalisation, and oil exportation are controlled for. Yet these results likely underestimate the total impact of economic freedom on civil war. ‘In reality’, write De Soysa and Fjelde (2010, p. 293), ‘the effect of economic freedom on peace is likely to be larger if we also take into account the indirect effect of economic freedom through its impact on income growth’. These findings correspond with a later study by De Soysa and Flaten (2012), which controls for the same variables and finds that higher levels of globalisation (particularly economic globalisation) reduce the risk of civil war as well as state violations of human rights. Other research finds that free-market conditions and economic liberalisation are associated with lower levels of various societal insecurities, including open armed conflict, violent crime, murder, societal militarisation and political instability (Stringham and Levendis 2010; De Soysa 2011, 2016; Bjornskov 2015). Various organisations from the World Economic Forum (2016) to the UN Global Compact (2014) are recognising the power commerce has to decrease conflict and establish peace (pg. 426-429).

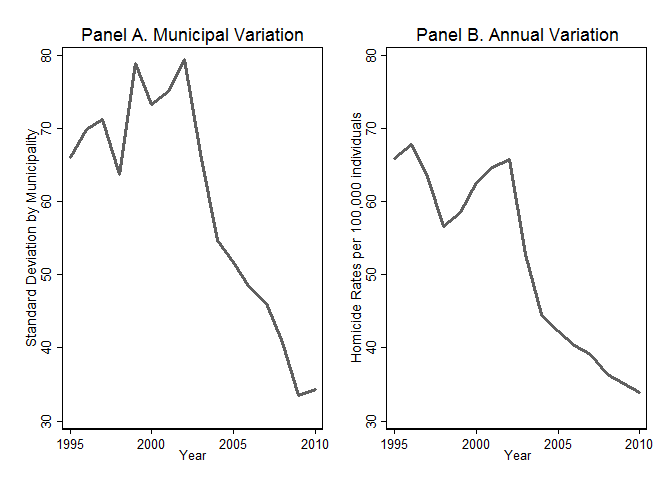

A brand new study looks at the relationship between violence and business by examining Columbia’s reduction in violence between 1995 and 2010.

The author explains,

To precisely measure the effects of violent crime on firm behaviour, I use the large reductions in violence caused by increased security expenditures of the Democratic Security programme under Uribe’s administration. According to the Uribe’splan published in 2003, the Democratic Security programme aimed at restoring police presence in all municipalities; dismantling terrorist organisations; reducing kidnappings, extortion, and homicides; preventing forced displacement; and fighting the illegal drug trade (Ministerio de Defensa 2003). Uribe’s government intended to achieve these goals by increasing spending on military infrastructure, personnel, and intelligence. High spending on security led to decreased violence in municipalities that voted for Uribe in the presidential elections of 2002 (when he was elected for the first time) as he was looking for re-election in 2006 (he was re-elected).

…I combine unique plant-level and rich consumer pricing data with homicide rates and electoral results in Colombia. Using these data, I compare the prices and market size of Colombian municipalities that showed higher and lower support for Alvaro Uribe in the presidential election of 2002. These correlations were subsequently reflected in larger or lower changes in homicide rates.

I find large effects due to changes in violent crime:

– When violence decreases by 1%, firm aggregate production increases by approximately 0.4%. This is partly explained by higher production per firm but also explained by the entrance of new firms into the market.

– Real income increases in areas with less violence. These changes are explained by higher nominal wages, which are larger in size than the documented increases in the general price levels.

– Consequently, areas with lower violent crime have higher incomes. This condition may further reduce social unrest and violence.

In conclusion, a “48% decline in homicide rates between 1995 and 2010 in Colombia increased aggregate production by 19.6%. My estimates, however, are a lower bound of the total social costs of violent crime, as they are do not include the costs of mortality or the long-run impacts of violent crime reductions. The benefits of reducing violence, consequently, are even higher. Investments in security improvements are thus an effective way to boost economic development.”

Violence, it seems, is antithetical to business. As I note in my paper, “findings that ‘merely’ demonstrate positive correlations [between markets and morality] should be interpreted in light of the feedback loops: even if moral behaviours are foundational and give rise to market systems (instead of vice versa), market systems in turn reinforce these virtues by imbuing them with value” (pg. 423).