It sure looks that way. According to a recent study,

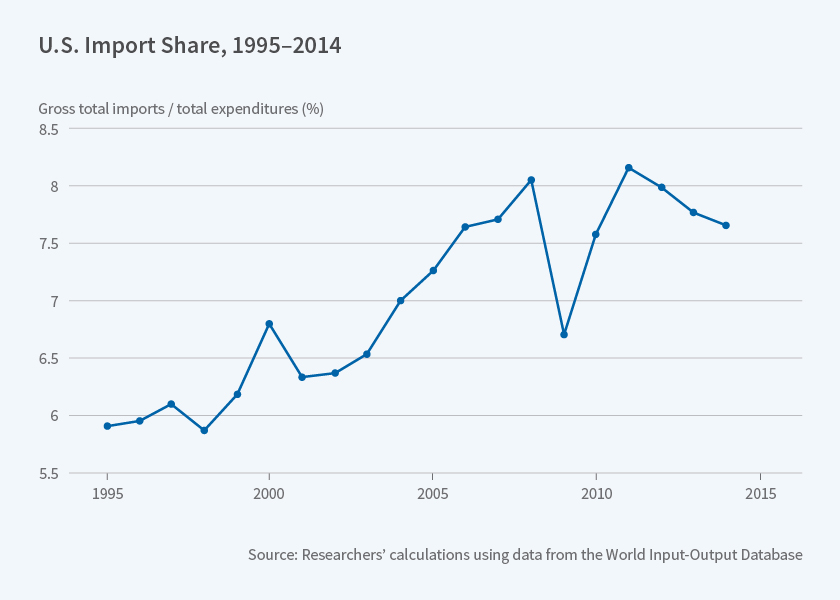

Assessing the size and identifying the sources of gains from trade is a long-standing challenge for economists. Theoretical and quantitative studies have mostly focused on static economies where changes in international market integration have only one-off effects on the levels of income and consumption but do not affect the long-run dynamics of these key economic variables (Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare, 2014). Since innovation and technological change are key drivers of income growth in the long-run (Aghion and Howitt, 2009, Akcigit et al. 2017), in a recent paper (Impullitti and Licandro 2018) we explore the sources and assess the size of the gains from trade in an economy where growth spurs from technological progress.

Building a quantitative model for policy analysis requires a theory sufficiently grounded on a (large enough) set of relevant empirical facts. We focus on the following facts, each corresponding to a particular channel of gains from trade.

- First, there is strong evidence documenting competition effects of trade (Feenstra and Weinstein 2017). Increasing foreign competition is often found to reduce firm prices thereby shrinking their profit margins. Lower prices benefit consumer by increasing their purchasing power, this is the so-called pro-competitive effect of trade.

- Second, the reduction in profits forces some of the less-profitable and less-productive firms out of the market, thereby reallocating market shares toward the most productive firms (Bernard et al. 2012). This selection effect generates an additional channel of gains from trade, as more productive firms charge lower prices.

- Finally, foreign competitive pressure and selection, along with access to foreign markets induce firms to increase their investment in innovation to improve productivity and stay ahead of competitors (Bloom et al. 2015, Aghion et al. 2017). This innovation effect leads to dynamic gains from trade, as higher productivity growth produces not just one-off price reductions but a sequence of reductions across time, thereby increasingly benefiting present and future consumers.

We construct a model embedding all three key channels through which trade can potentially increase average income and consumption and calibrate it to replicate key aggregate and firm level trade and innovation statistics of the US economy. Frontier quantitative trade models embed only the first two channels in static economies where the effects of a policy change take place through timeless reallocations of market shares across firms and sectors but each firm’s productivity is kept constant. The selection and competition effects of trade reallocates resources toward the most productive firms, thereby increasing the average level of productivity and reducing prices. In our dynamic economy, trade-induced reallocations increase the size of the most productive firms and raise their incentives to innovate, thereby pushing up the growth rate of productivity. Hence, the model is able to separately measure the static gains form competition and selection and the dynamic gains produced by the interaction of these forces with innovation-driven productivity growth.

The authors’ findings

suggest that policy evaluation with static trade models is likely to largely underestimate the gains from globalisation. We have shown that innovation can be a key driver of dynamic gains from trade. Other recent papers have suggested that dynamic gains from trade can also come via technology diffusion (Sampson, 2016, Perla and Tonetti, 2016), and also stressed the importance of quantifying both the short and long-run effects of trade by exploring the full transitional dynamics generated by trade shocks (Akcigit, et al. 2018). This new class of macro-trade models have laid the basis for future quantitative frameworks to measure the effects of globalisation on per-capita income and consumption.

Immigration policy is controversial topic in 2018. In response to refugee crises and legal situations that can break up families, the LDS Church announced its “I Was a Stranger” relief effort and released a statement encouraging solutions that strengthens families, keeps them together, and extends compassion to those seeking a better life. This article seeks to shed light on a correct understanding of immigration and its effects. Walker Wright gives a brief scriptural overview of migration, explores the public’s attitudes toward immigration, and reviews the empirical economic literature, which shows that (1) fears about immigration are often overblown or fueled by misinformation and (2) liberalizing immigration restrictions would have positive economic effects.

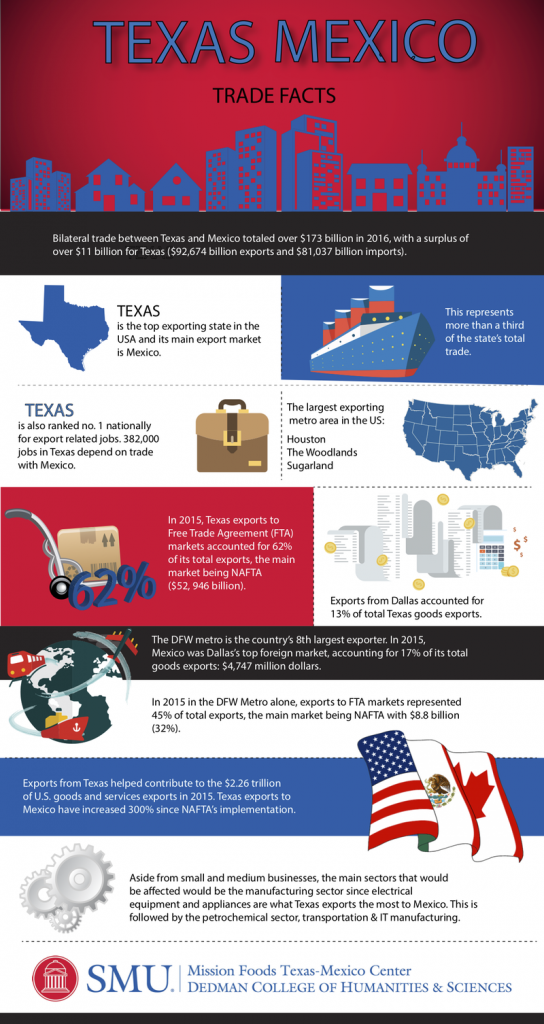

Immigration policy is controversial topic in 2018. In response to refugee crises and legal situations that can break up families, the LDS Church announced its “I Was a Stranger” relief effort and released a statement encouraging solutions that strengthens families, keeps them together, and extends compassion to those seeking a better life. This article seeks to shed light on a correct understanding of immigration and its effects. Walker Wright gives a brief scriptural overview of migration, explores the public’s attitudes toward immigration, and reviews the empirical economic literature, which shows that (1) fears about immigration are often overblown or fueled by misinformation and (2) liberalizing immigration restrictions would have positive economic effects. There is surprisingly little direct quantitative evidence on how the U.S. economy would react if the door were shut on trade. To find a precedent, the researchers point out that one could go back to the Embargo Act of 1807, when the United States banned trade with Great Britain and France in retaliation for their repeated violations of U.S. neutrality. GDP declined sharply, but the agrarian world during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson bears little resemblance to today’s high-tech, service-oriented economy.

There is surprisingly little direct quantitative evidence on how the U.S. economy would react if the door were shut on trade. To find a precedent, the researchers point out that one could go back to the Embargo Act of 1807, when the United States banned trade with Great Britain and France in retaliation for their repeated violations of U.S. neutrality. GDP declined sharply, but the agrarian world during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson bears little resemblance to today’s high-tech, service-oriented economy.

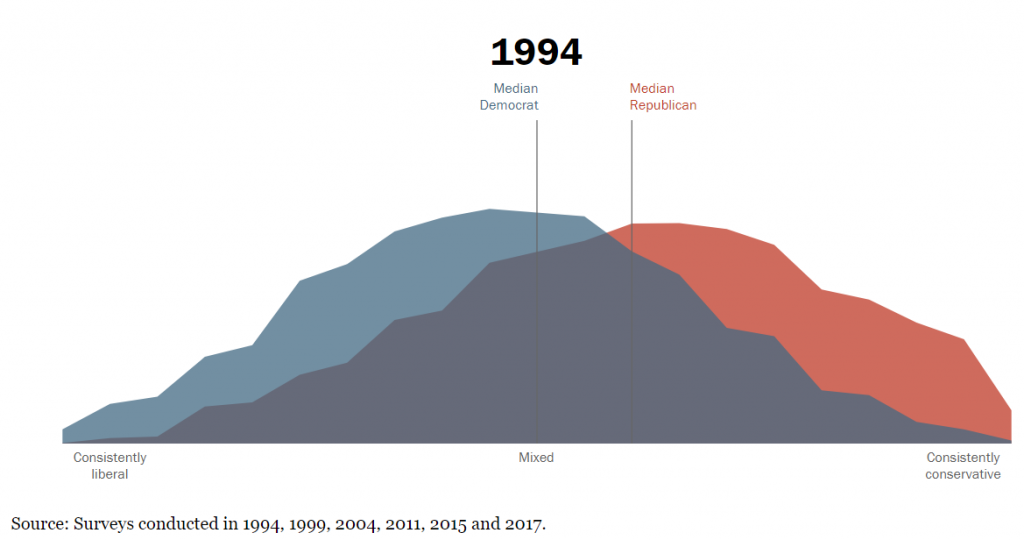

You might think that politics is an area where being analytical is especially useful. If you do, well, I have news for you: Libertarians measure as being the most analytical political group. That’s according to something called the

You might think that politics is an area where being analytical is especially useful. If you do, well, I have news for you: Libertarians measure as being the most analytical political group. That’s according to something called the