From a recent St. Louis Fed study:

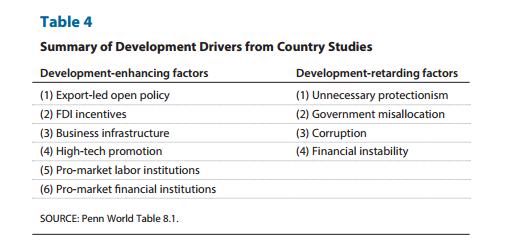

Using cross-country analysis, we find that a key factor for fast-growing countries to grow faster than the United States and for trapped economies to grow slower than the United States is the relative TFP, which may be technology driven and not related to institutional barriers. Yet more-severe institutional barriers in the lag-behind countries actually hinder the process of structural transformation and economic development, causing these countries to fall behind the fast-growing economies despite having similar or even better initial states five decades ago. Overall, we find that institutional barriers have played the most important role, accounting for more than half the economic growth in fast-growing and trapped economies and for more than 100 percent of the economic growth in the lag-behind countries. By conducting country studies, we identify that unnecessary protectionism, government misallocation, corruption, and financial instability have been key institutional barriers causing countries to either fall into the poverty trap or lag behind without a sustainable growth engine. Such barriers have created frictions or distortions to capital markets, trade, and industrialization, subsequently preventing these countries from advancing (pg. 260-261).

Economist Linda Yueh explains why institutions are important for economic growth:

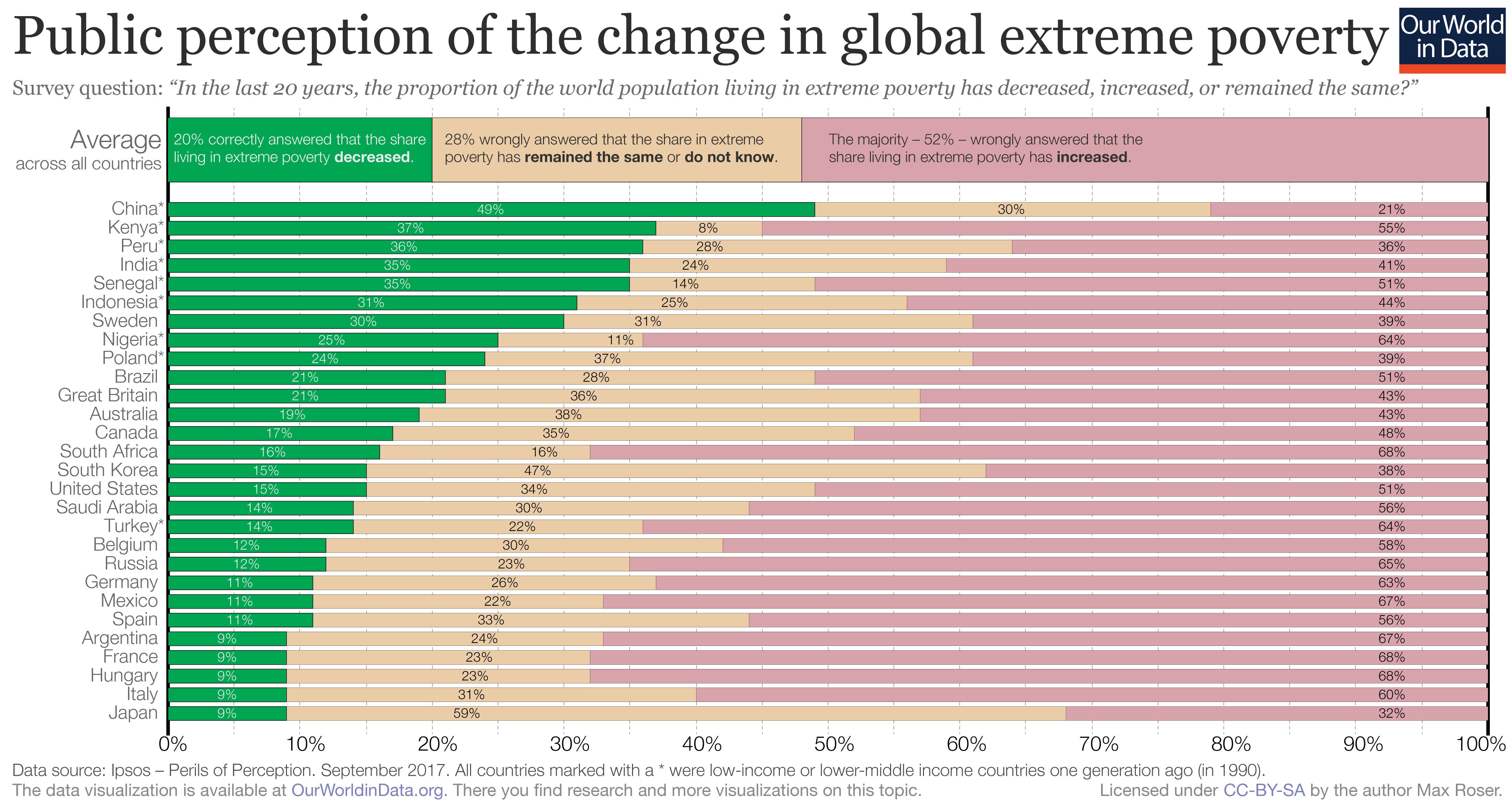

Research by the OECD estimates that by 2030, for the first time in history, more than half of the world’s population will be middle class (OECD 2012). That’s 4.9 billion out of an estimated 8.6 billion people. In 2009 1.8 billion (out of around 7 billion) people earned between $10 and $100 per day, a measure of the income that defines the new global middle class. That’s enough to buy a refrigerator, adjusted for what a dollar buys in their countries.

Based on current trends, in 2030 around two-thirds of the middle classes worldwide – nearly 3 billion people – will be in Asia. The UN describes it as a historic shift not seen for 150 years (Yueh 2018). The European and North American middle classes will fall from more than half of that class’s world total to one-third.

How has this been achieved? Possessing good institutions is what economists have come to focus on and the spread of such institutions seems to have been key, as the father of New Institutional Economics predicted. The seminal work in this area was by Douglass North who was frustrated by neoclassical economic models that focused on measurable factors like workers and investment, with attempts to measuring technological progress, even though they could not fully explain why some economies grow well and others do not.

So, North took economics out of its comfort zone, which consisted of examining more easily measured inputs like labour and capital, and instead brought in politics, psychology, and strategy, as well as history, in order to understand why some countries succeed and others fail. He stressed that there was no reason why countries could not learn from more successful economies to better their own institutions. That finally happened in the 1990s.

In the early 1990s, China, India, and Eastern Europe changed course. China and India re-oriented their economies outward to integrate with the world economy, while Eastern Europe shed the old communist institutions and adopted market economies. In other words, having tried central planning (in China and the former Soviet Union) and import substitution industrialisation (in India), these economies abandoned their old approaches and adopted as well as adapted the economic policies of more successful economies. For instance, China, which has accounted for the bulk of poverty reduction since 1990, undertook an ‘open door’ policy that sought to integrate into global production chains which increased competition into its economy that had been dominated by state-owned enterprises. India likewise abandoned its previous protectionist policies and embraced exports to a greater extent. The wholesale transformation of the economic system was of course in Central and Eastern Europe. Communism gave way to capitalism, with these nations adopting entirely new institutions that re-geared their economies toward the market and many joining the EU.

Thus, the 1990s witnessed the rapid growth of emerging economies whose growth via industrialisation eventually led to an extraordinary commodity super-cycle due to their voracious demand for raw materials to fuel their development. As many of these economies, especially China, have become middle-income countries, their economic growth is slowing down. And they may slow down so far that they never become rich. But, their collective growth has lifted a billion people of out of extreme poverty, and the UN hopes that their continued growth will lead to the end of abject poverty in the next decade or so, which would be a historic achievement. That would realise the first of the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by every nation around the world to end extreme poverty – i.e. those earning less than $1.90 per day adjusted for what a dollar buys in their country – by 2030.

Institutions matter.