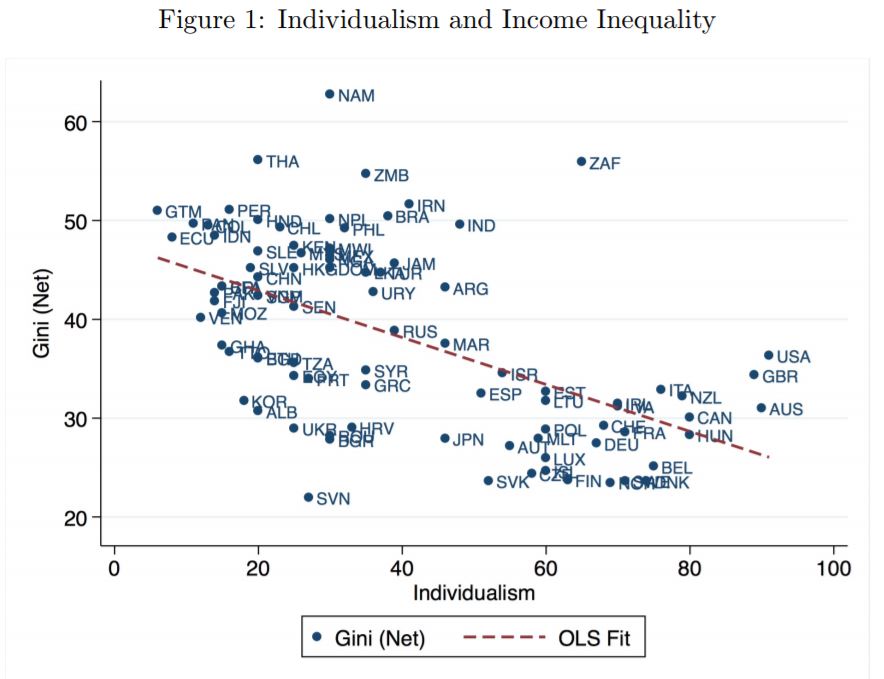

That appears to be the case, according to a 2017 paper. From a working paper version,

Our results challenge the conventional view that individualistic societies are more prone to higher levels of income inequality. On the contrary, we find that even if people in more individualistic cultures are more likely to accept and encourage greater individual differences, they end up living in far more equal societies at the end of the day. In our 2SLS analysis, we find that the historical prevalence of infectious diseases is strongly and negatively correlated with individualistic values, which then, in the next stage, are a strong determinant of economic inequality, measured by the net GINI coefficient from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID). These results hold even when we control for a number of confounding factors including the level of economic development, social capital, formal institutions, local factor endowments, geographic dummies, and other cultural values. The results are furthermore robust to different sub-samples of countries and alternative measures of income inequality and individualism.

One possible explanation for these findings is that citizens in individualistic cultures favor more inclusive institutions that are characterized by respect for the rights, liberties, and well-being of all members of society, not just their immediate circle. This is consistent with recent empirical findings which show that more individualistic societies are far more likely to develop high quality political and economic institutions including respect for the rule of law, protection of private property and strong democratic institutions (Greif, 1994; Nikolaev and Salahodjaev, 2017; Kyriacou, 2016; Nikolaev and Salahodjaev, 2016; Gorodnichenko and Roland, 2015; Licht et al., 2007; Inglehart and Oyserman, 2004). People in more individualistic cultures are also more likely to tolerate minorities and have higher levels of interpersonal trust and lower levels of corruption (Thornhill and Fincher, 2014; Allik and Realo, 2004), which can further reduce transaction costs and facilitate market exchange leading to higher rates of human and physical capital investment, technological innovation and long-run economic growth (Oyserman et al., 2002; Gorodnichenko and Roland, 2012) and encouraging people to put more effort and get a fairer share of the economic pie (Alesina and Angeletos, 2005). When citizens perceive state institutions to be fair, less corrupt, and more efficient, they are far more likely to tolerate higher taxes and government spending on welfare programs (Dimitrova-Grajzl et al., 2012; Svallfors, 2013; Pitlik and Kouba, 2015; Daniele and Geys, 2015; Pitlik and Rode, 2016). When they trust and care about the wellbeing of their fellow citizens, they will be more inclined to support welfare programs that benefit others. Finally, when people earn higher incomes, they are more likely to be able to bear the burden of higher taxation while still maximizing their own talents through their free choices (pgs. 3-4).

America should abolish prisons. Perhaps not all of them, but very close to it.

America should abolish prisons. Perhaps not all of them, but very close to it.

Women worldwide tend to be more religious than men

Women worldwide tend to be more religious than men