There’s an absolutely fascinating article on crowd psychology in aeon that I’ve been meaning to share for several weeks now. The article questions and rejects the conventional wisdom on crowds, which focuses on violent mobs and on the idea that, once they had joined, individuals had “surrendered their self-awareness and rationality to the mentality of the crowd.” In contrast to a kind of brute mob mentality, modern research supports the conception of crowds in which “crowds behave not with mindlessness or madness, but by co-operating with those around them. They do not lose their heads but instead act with full rational intent.”

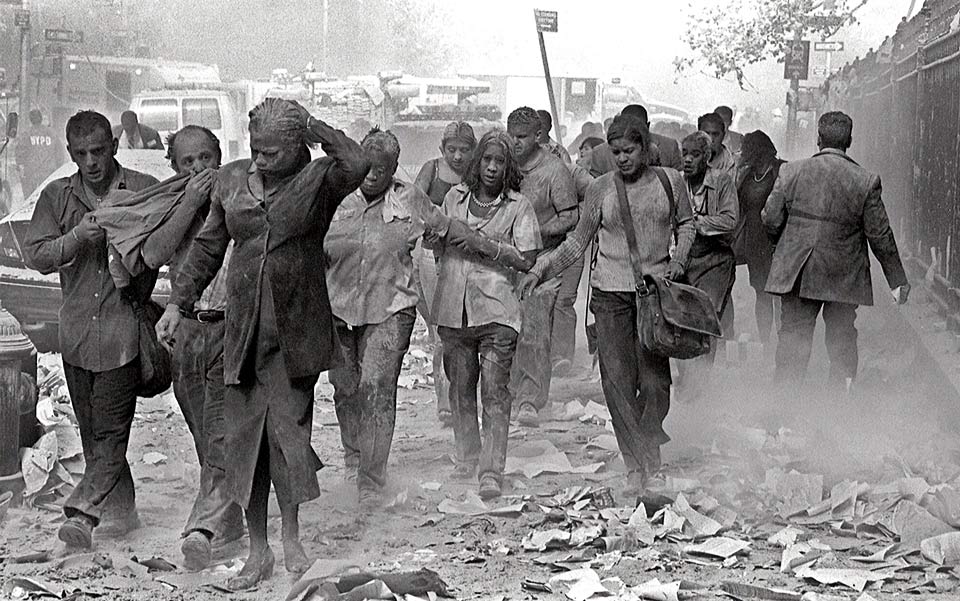

That approach might sound counterintuitive, but that makes sense because in reality crowds don’t actually behave the way they are supposed to in popular imagination. And so, “the model also explains why crowds in emergency situations are disinclined to panic, putting them at higher risk.” The article cites many people who milled around in the Two Towers 13 years ago instead of immediately fleeing, which is something they might have been much more prone to do if they’d been alone, and also cites several other disturbing historical accounts such as “the aircraft fire at Manchester airport in the UK on 22 August 1985, when 55 people died because they stayed in their seats amid the flames.”

This isn’t the first I’ve read of this research. Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist who invented moral foundations theory, has done a lot of work on crowds and his theories are closely related to the idea of a “superorganism“. A superorganism is “an organism consisting of many organisms,” and the textbook example is a beehive. A beehive is not just a collection of bees. It can be thought of as a creature in its own right that happens to be made up of bees in the same kind of way (although not exactly, obviously) that we human beings are made up of many cells. The human capacity for “groupish behavior,” which is to say behavior that doesn’t make sense from a strictly individualistic standpoint, is a major differentiator and perhaps the essential differentiator between humans and all other primates. This gets into group-level selection, which is something that Darwin believed in but which has only been rigorously outlined and defended very recently. Group-level adaptation is the idea that not just individuals are evolving as they compete for resources, but groups of individuals, too. Like beehives. Human capacity to function as individuals or, when circumstances are right, to lose themselves in part of a larger collective are the reason Haidt describes us as “90% chimp, 10% honeybee.”

Keep that in mind when you read this next sentence about crowd behavior:

Contrary to popular belief that crowds always panic in emergencies, large groups mill around longer than small groups since it takes them more time to come up with a plan.

In a real sense, it’s not that the individuals within the group take longer to come up with a plan. it’s that the group itself takes longer to come up with a plan when it’s a bigger group.

There isn’t just one pithy practical or political implication of this research. It’s the kind of fundamental change in how we look at the world that can end up taking you in any one of thousands of different directions. To me, it’s just another part of the major advances in understanding human nature that are becoming possible now that we’re developing some rudimentary tools for analyzing complex systems.