When David Hume said that “reason is…the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.”[ref]I have intentionally edited out the phrase “and ought only to be” where those ellipses go. I agree with that claim, too, but what ought to be is separate from what already is, and I want to focus on the is in this post.[/ref], he thought it would “appear somewhat extraordinary.” Maybe it did in the mid-18th century, but a 21st century audience takes this assertion in stride. It’s not that human nature has changed. Humans have always held opinions and they’ve always been held for non-rational reasons. What’s changed is that we’re more aware of the extent of our opinions and of their frequently irrational nature.

We’re more aware of this for two reasons. First, the narcissism of social media and the tribally partisan nature of our society make us painful aware of everybody else’s opinions. As a group, we can’t shut up about the things we think are obviously true, even though things that really are obviously true (like the sky being blue) don’t generally require frequent reminders in the form of snarky memes.

Second, there’s a growing body of research into the reasons and mechanisms by which humans acquire and maintain their beliefs. It’s become so trendy to talk about cognitive biases, for example, that the Wikipedia list of them is becoming a bit of a joke. Still, the underlying premise–that human reason is about convenience and utility rather than about truth–is increasingly undeniable and books like Thinking, Fast and Slow or Predictably Irrational[ref]There are many, many more along this vein.[/ref] make that undeniable reality common knowledge.

In fact, we can now go farther than Hume and say that not only is reason the slave of the passions, but that it is only thanks to the passions that humans evolved the capacity for reason at all. This is known as the Argumentative Theory, which researchers Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber summarized like this:

Reasoning is generally seen as a means to improve knowledge and make better decisions. However, much evidence shows that reasoning often leads to epistemic distortions and poor decisions. This suggests that the function of reasoning should be rethought. Our hypothesis is that the function of reasoning is argumentative. It is to devise and evaluate arguments intended to persuade. Reasoning so conceived is adaptive given the exceptional dependence of humans on communication and their vulnerability to misinformation.[ref]From “Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory” by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber. Full text.[/ref]

Oddly enough, I can’t find a Wikipedia article to summarize this theory, but it’s been cited approvingly by researchers I respect like Frans de Waal[ref]In The Bonobo and the Atheist, page 89[/ref] and Jonathan Haidt, who summarized it this way: “Reasoning was not designed to pursue the truth. Reasoning was designed by evolution to help us win arguments.”[ref]In “The New Science of Morality,” excerpted here.[/ref]

If the theory is right, then the human tendency to believe what is useful and then to express those beliefs in ways that are farther useful is part of the story of how humanity came to be. This might have been deniable in Hume’s day, requiring an iconoclastic genius to spot it, but it’s becoming a humdrum fact of life in our day.

Our beliefs are instrumental. That is, we believe things because of the usefulness of holding that belief, and that usefulness is only occasionally related to truth. If the belief is about something that’s going to have a frequent and direct effect on our lives–like whether cars go or stop when the light is red–then it is very useful to have accurate beliefs and so our beliefs rapidly converge to reality. But if the belief is about something that is going to have a vague or indeterminate effect on our lives–and almost all political beliefs fall into this category–then there is no longer any powerful, external incentive to corral our beliefs to match reality. What’s more, in many cases it would be impossible to reconcile our beliefs with reality even if we really wanted to because the questions at play are too complicated for anyone to answer with certainty. In those cases, there is nothing to stop us from believing whatever is convenient.

And it’s not just privately-held beliefs that are instrumental. Opinions–the expression of these beliefs–add an additional layer of instrumentality. Not only do we believe what we find convenient to believe, but we also express those beliefs in ways that are convenient. We choose how, when, and where to express our opinions so as to derive the most benefit for the least amount of effort. Benefits of opinions include:

- maintaining positive self-image: “I have such smart, benevolent political opinions. I’m such a good person!”

- reinforcing community ties: “Look at these smart, benevolent political opinions we have in common!”

- defining community boundaries: “These are the smart, benevolent political opinions you have affirm if you want to be one of us!”

- the buzz of moral superiority: “We have such smart, benevolent political opinions. Not like those reprehensible morons over there!”

Opinions aren’t just tools, however. They are also weapons. If you want to understand what I’m talking about, just think of all the political memes you see on your Facebook or Twitter feeds. They are almost always focused on ridiculing and delegitimizing other people. This is about reinforcing community ties and getting high off of moral superiority, but it is also about intimidating the targets of our (ever so righteous) contempt and disdain. We live in an age of weaponized opinion.

Which brings me to the idea of a demilitarized zone.

A demilitarized zone is an “is an area in which treaties or agreements between nations, military powers or contending groups forbid military installations, activities or personnel.”[ref]Wikipedia[/ref] The term is also used in the context of computers and networking. In that case, a DMZ is a part of a private network that is publicly accessible to other networks, usually the Internet. It’s a tradeoff between accessibility and security, allowing interaction with anonymous, untrusted computers but restricting that access to only specially designated computers in your network that are placed in the DMZ, while the rest of your computers are stored behind a defensive firewall.

The same concepts make sense in an ideological framework.

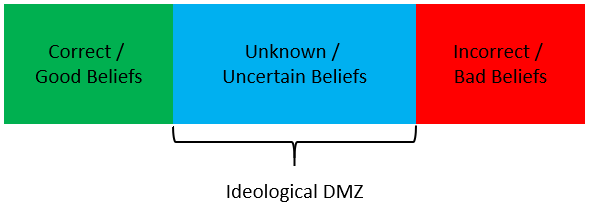

A typical partisan might have a range of beliefs that looks something like this:

The green section doesn’t represent what is actually good / correct. It represents what a person asserts to be correct / good. The same applies for the red portion. So, these will be different for different people. If you are, for example, someone who is pro-life then the green category will include beliefs like “all living human beings deserve equal rights” and the red portion will include beliefs like “consciousness and self-awareness are required for personhood”. If you are pro-choice, then the chart will look the same but the beliefs will be located in the opposite regions.

And here’s what it looks like if you introduce an ideological DMZ:

The difference here is that we have this whole new region where we are refusing to categorize something as correct / good or incorrect / bad. This may seem like an obvious thing to do. If, for example, you hear a new fact for the first time and you don’t know anything about it, then naturally you should not have an opinion about it until you find out more, right? Well, if humans were rational that would be right. But humans are not rational. We use rationality as a tool when we want to, but we’re just as happy to set it aside when it’s convenient to do so.

And so what actually happens is that when you hear a new proposition, you (automatically and without thinking about it consciously) determine if the new proposition is relevant to any of your strongly-held political opinions. If it is, you identify if it helps or hurts. If it helps, then you accept it as true. Maybe you use the same “fact” in your next debate, or share the article on your timeline, or forward it to your friends. In other words, you stick it into the green bucket. If it hurts, you reject it as false. You attack the credibility of the person who shared the fact or thrust the burden of proof on them or even jump straight to attacking their motives for sharing it in the first place. You stick it in the red bucket.

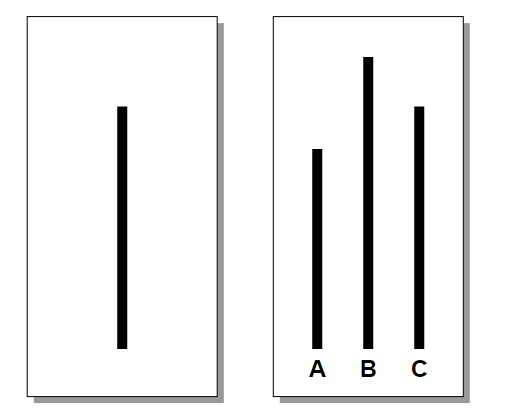

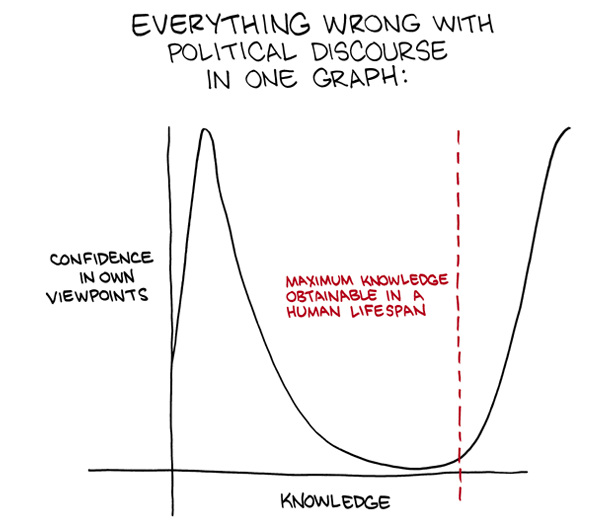

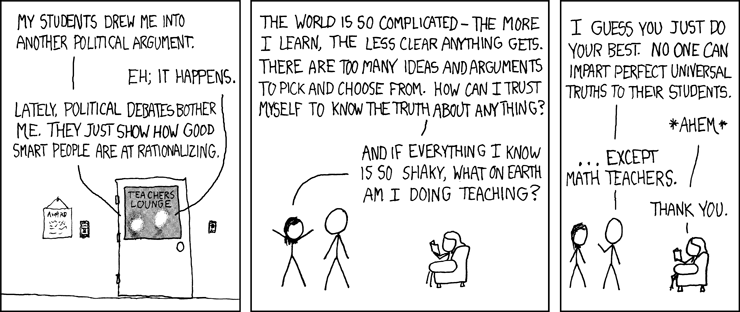

If you’re following along so far, you might notice that what we’re talking about is certainty. One of the popular and increasingly well-known facts about human beings and certainty is that certainty and ignorance go hand in hand. The technical term for this is the Dunning-Kruger effect, “a cognitive bias in which people of low ability have illusory superiority and mistakenly assess their cognitive ability as greater than it is.”[ref]Wikipedia[/ref] Even if you’ve never heard that term, however, you’ve probably seen webcomics like this one from Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal:

Or maybe this one from xkcd:

The idea of a DMZ is related to these concepts, but it’s not the same. These comics are about the vertical ignorance/certainty problem. Lack of knowledge combined with instrumental beliefs cause people to double-down on convenient beliefs they already have. That’s a real problem, but it’s not the one I’m tackling. I’m talking about a horizontal ignorance/certainty problem. Instead of pouring more and more certainty into (ignorant, but convenient) beliefs that we already have, this problem is about spreading certainty around to different, neighboring beliefs that are new to us.

How does that play out in practice? Well, as a famous study revealed recently, “people who are otherwise very good at math may totally flunk a problem that they would otherwise probably be able to solve, simply because giving the right answer goes against their political beliefs.” [ref]Mother Jones[/ref] That’s because–without a consciously defined and maintained DMZ–they immediately categorize new information into the red or green region even if it means magically becoming bad at math. That’s how strong the temptation is to sort all new information into friend/foe categories is, and it’s the reason we need a DMZ.

So what does having a DMZ mean? It means, as I mentioned earlier, that you can easily list of several arguments or propositions which might work against your beliefs, but that you don’t reject out of hand because you simply don’t know enough about them. It doesn’t mean you have to accept them. It doesn’t mean you have to reject the belief that they threaten. It doesn’t even mean you have investigate them right away.[ref]Obviously that’s a good idea, but in practice none of us have infinite research time.[/ref]. It just means you refrain from categorizing them in the red bucket. And you do the same with new information that helps your cause. If it is about a topic you know little about, then you go ahead and put it in that blue bucket. You say, “That sounds good. I hope it’s true. But i’m not sure yet.”

There’s another aspect to this as well. So far I’ve been talking about salient propositions, that is: propositions that directly relate to some of your political beliefs. I’ve been leaving aside irrelevant facts. That’s because–although it’s easy for anyone to stick irrelevant facts in the blue bucket–the distinction between relevant and irrelevant facts is not actually stable or clear cut.

One of the problems with our increasingly political world is that more and more apparently unrelated facts are being incorporated into political paradigms. There’s a cottage industry for journalists to fill quotas by describing apparently innocuous things as racist. A list of Things college professors called ‘racist’ in 2017 includes math, Jingle Bells (the song), and punctuality. This is a controversial topic. Sometimes, articles like this really do reveal incisive critiques of racial inequality that’s not obvious at first. Sometimes conservatives misrepresent or dumb-down these arguments just to make fun of them. But sometimes–like when a kid in my high school class complained that it was sexist to use the term for a female hero (heroine) as the name for a drug (heroin)–the contention really is silly.[ref]Our teacher gently explained that they aren’t even the same words.[/ref] And so part of the DMZ is also just being a little slower to see new information in a political light. Everything can be political–with a little bit of rhetorical ingenuity–but there’s a big difference between “can” and “should”.

If you don’t have an ideological DMZ yet, I encourage you to start building one today. In networking, a DMZ is a useful way to allow new information to come into your network. An ideological DMZ can fill the same function. It’s a great way to start to start to dig your way out of an echo chamber or avoid getting trapped in one in the first place. In geopolitics, a DMZ is a great way to deescalate conflict. Once again, an ideological DMZ can fill a similar role. It’s a useful habit to reduce the number of and lower the stakes in the political disagreements that you have.

Even after all these years, North and South Korea are technically still at war. A DMZ is not nearly as good as a nice, long, non-militarized border (like between the US and Canada). And so I have to admit that calling for an ideological DMZ feels a little bit like aiming low. It’s not asking for mutual understanding or a peace treaty, let alone an alliance.

But it’s a start.

I’m sure most of you have heard about the

I’m sure most of you have heard about the