According to The New York Times,

According to The New York Times,

The Environmental Protection Agency has concluded that hydraulic fracturing, the oil and gas extraction technique also known as fracking, has contaminated drinking water in some circumstances, according to the final version of a comprehensive study first issued in 2015. The new version is far more worrying than the first, which found “no evidence that fracking systemically contaminates water” supplies. In a significant change, that conclusion was deleted from the final study.

So why the change? Is there new evidence demonstrating that fracking is in fact a danger to water sources? Not really. CBS reports,

The government report notes concerns over well leaks and waste water spilling above ground. The agency didn’t pinpoint any damage related to the fracking deep underground itself. “What we found is that although the overall incidents of impacts is low, that there are vulnerabilities,” said EPA science adviser Thomas Burke. The EPA is taking a tougher stance than ever before. Language in an earlier draft of the report downplaying fracking concerns was removed. It said: “We did not find evidence that these mechanisms have led to widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources.” Burke explained why they omitted the lighter language. “The gaps in information unfortunately do not allow us to say how much, what is the rate of the impact. And so that sentence was removed,” Burke said.

Elsewhere, Burke told reporters, “While the number of identified cases of drinking water contamination is small, the scientific evidence is insufficient to support estimates of the frequency of contamination…Scientists involved with finalising the assessment specifically identified this uncertainty in the report.”

The above can hardly be interpreted as a seismic, anti-fracking change. Science writer Ronald Bailey observes,

First, most of the instances and speculations cited in the EPA report are applicable to all oil and gas wells, not just to wells created by means of fracking. These include harms caused by spills, leaks due to faulty well casings, and inadequate treatment and disposal of fluids and water that flow from wells.

Focusing chiefly on the process of fracking itself—creating cracks by injecting pressurized fluids into shale rocks as a way to release trapped oil and natural gas—the EPA report looks at four pathways by which fracking specifically could contaminate drinking water supplies. Most of the agency’s findings are couched in conditional language. They include the possibility that fluids and natural gas could migrate via fracked cracks that might extend directly into drinking water aquifers; because well casings for horizontal drilling might be less able to withstand the high fracking pressures they may be more likely to leak allowing contaminants to migrate; migration might occur when a fracked well “communicates” with a nearby previously drilled well that is not able to withstand the additional pressures from newly released natural gas; and fracked cracks might intersect with natural faults allowing contaminants to migrate into drinking water supplies.

The EPA cites the results of lots of computer models that find that migration of fluids and natural gas by these four pathways is possible. However, given the fact that by some estimates as many as 35,000 fracked oil and gas wells are drilled each year in the United States, it is astonishing how few examples of actual contamination and other harms are identified in the EPA report…Given even the limited quantitative findings in the EPA’s final report, the agency should have reaffirmed its original more qualitative statement that there is little “evidence that these mechanisms have led to widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources.”[ref]Bailey has more to say about global environmental trends.[/ref]

Read the report for yourself: “However, significant data gaps and uncertainties in the available data prevented us from calculating or estimating the national frequency of impacts on drinking water resources from activities in the hydraulic fracturing water cycle” (pg. 2). The 2015 draft report read, “We did not find evidence that these mechanisms have led to widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources in the United States” (pg. 6). These two reports communicate virtually the same thing. The newest report still, to quote the draft, “did not find evidence that these mechanisms have led to widespread, systemic impact on drinking water resources in the United States.” The language is simply massaged to emphasize “data gaps and uncertainties.” Both the draft and final reports acknowledge that fracking can impact drinking water sources under certain circumstances. That’s not a revelation. What the draft highlighted was the infrequency of these incidents. What the new report highlights is a lack of good data to quantify the frequency. However, the takeaway for the scientifically minded is nearly identical: there is no evidence that fracking has “led to widespread, systemic impact on drinking water resources.” Nonetheless, better data and continual research is needed (absence of evidence is not evidence of absence and whatnot).

Future evidence may indeed condemn fracking mechanisms or at least call for better regulations. For now, that evidence is sorely lacking. Natural gas is both economically and environmentally beneficial. We need to be careful not to squash it due to faulty interpretations of government reports.

Historically, U.S. economic growth has gone hand-in-hand with the regional reallocation of labor and capital. The pace of resource reallocation, however, has slowed considerably. This decline has roughly coincided with lower productivity and output growth, as well as growing home price premia in high income states, including California and New York.

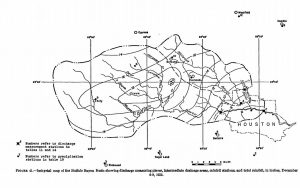

Historically, U.S. economic growth has gone hand-in-hand with the regional reallocation of labor and capital. The pace of resource reallocation, however, has slowed considerably. This decline has roughly coincided with lower productivity and output growth, as well as growing home price premia in high income states, including California and New York. the following map of the Houston storm’s effects, showing unsettling similarities to what we just witnessed (note that this map does not include the areas to the north of town, where rainfall in 1935 was significantly higher. These are the suburbs that flooded along Cypress and Spring Creeks last weekend and the farmland that similarly flooded in 1935)

the following map of the Houston storm’s effects, showing unsettling similarities to what we just witnessed (note that this map does not include the areas to the north of town, where rainfall in 1935 was significantly higher. These are the suburbs that flooded along Cypress and Spring Creeks last weekend and the farmland that similarly flooded in 1935)

According to

According to

Most people are in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar, yet many supporters tend to look at natural gas with disdain.[ref]Arguably due to the means of its extraction (fracking). For example, there’s been

Most people are in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar, yet many supporters tend to look at natural gas with disdain.[ref]Arguably due to the means of its extraction (fracking). For example, there’s been