One letter makes a load of difference in this case. (Or does it?)

I had another dream, I had another life

That was the question a self-described “white, male poet—a white, male poet who is aware of his privilege and sensitive to inequalities facing women, POC, and LGBTQ individuals in and out of the writing community” asked at The Blunt Instrument (“a monthly advice column for writers”). Well, more specifically, he said:

It feels like a Catch-22. Write what you know and risk denying voices whose stories are more urgent; write to learn what you don’t know and risk colonizing someone else’s story. I genuinely am troubled by this. I want to listen but I also want to write—yet at times these impulses feel at odds with one another. How can I reconcile the two?

The response took a long, convoluted, and circuitous route to get where it was going, but the basic answer was simple: Yes, stop writing. Or, more specifically, you can go ahead and write all you like, but you should stop trying to get your works published.

Don’t be a problem submitter. When I edited a magazine, we got far more submissions from men, and men were far more likely to submit work that was sloppy and/or inappropriate for the magazine; they were also far more likely to submit more work immediately after being rejected. When you submit writing, you’re taking up other people’s time. Be respectful of that. I said in my last column that getting published takes a lot of work, which is true—but most of that work should take the form of writing, and revising, and engaging with people in the writing world, not just constantly sending out new work, which starts to look like boredom and entitlement.

Think of this as something like carbon offsets. You are not going to solve the greater problem this way, on your own, but you might mitigate the damage.

It’s vague enough for plausible deniability, but the logic is clear. The only way to “mitigate the damage” is to submit fewer works. Publish less.

This is the logic behind the social justice movement. It’s not always as clear cut as this, but it’s always there. For a fantastic article documenting just how long this mentality has been around, I recommend Privilege and the working class. I don’t agree with all of it (obviously, as it is printed in The Socialist Worker), but the analysis of nascent social justice warrior ideology (aka “privilege theory”) is spot on:

Third, white workers were blamed for systemic racism because their “privileges” came, purportedly, at the expense of Blacks: white workers got more because Blacks got less, and vice versa. This assumption bought into the liberal capitalist idea that the size of the share of the economic pie available to workers is fixed and highly limited, and that different sub-groups of workers must fight against each other to expand their shares. Privilege theory focused on workers battling each other for the same shares, rather than on their fighting together for a just division of the share appropriated by the bosses–that fight, in the form of shop floor and union struggles for class demands, was explicitly opposed.

The analysis of capitalism is tragically and catastrophically off-base, but the insight that the essentially divisive nature of SJW ideology is itself a statist (and therefore elitist) tool is entirely valid. Once you accept the premise that we are fundamentally divisible into racial, sexual, and other categories, the possibility for cooperation and synergy disappears and all that is left is fighting over scraps.

The full quote from this anonymous professor is:

I’m a liberal professor, and my liberal students terrify me.

Through the rest of this Vox article he does his best to maintain his left-wing creds while at the same time arguing vociferously that social justice warriors have taken over college campuses and implemented an Orwellian regime of a very, very, very emotionally sensitive Big Brother.

In 2015… a complaint would not be delivered in such a fashion [as in 2009]. Instead of focusing on the rightness or wrongness (or even acceptability) of the materials we reviewed in class, the complaint would center solely on how my teaching affected the student’s emotional state. As I cannot speak to the emotions of my students, I could not mount a defense about the acceptability of my instruction. And if I responded in any way other than apologizing and changing the materials we reviewed in class, professional consequences would likely follow.

This is the elevation of subjective perception–call it post-modernism, relativism or whatever you like–over objectivity and realism. And it’s dangerous. Here’s another example (which I alluded to yesterday) from the Vox piece:

This sort of misplaced extremism is not confined to Twitter and the comments sections of liberal blogs. It was born in the more extreme and nihilistic corners of academic theory, and its watered-down manifestations on social media have severe real-world implications. In another instance, two female professors of library science publically outed and shamed a male colleague they accused of being creepy at conferences, going so far as to openly celebrate the prospect of ruining his career. I don’t doubt that some men are creepy at conferences — they are. And for all I know, this guy might be an A-level creep. But part of the female professors’ shtick was the strong insistence that harassment victims should never be asked for proof, that an enunciation of an accusation is all it should ever take to secure a guilty verdict. The identity of the victims overrides the identity of the harasser, and that’s all the proof they need.

The anonymous professor goes on to say “This is terrifying. No one will ever accept that.” And yet, as he knows too well, in at least one part of our society they already have.

Don’t get me wrong, I highly doubt that this particular brand of ideological insanity is about to take over the entire country. On a broad scale, it probably will be rejected, and soon. There’s been a steady drumbeat of articles from the left side of the American political spectrum over the last six months attempting to dismantle and/or disarm this particular section of their coalition. And it will likely succeed. Eventually. The question becomes: how much damage will be done in the interim? And also: how extensive will the rollback be? Because anyone who thinks the victory of reason is inevitable in the short run hasn’t read a lot of history. Think about the most silly, stereotypical caricature of scholasticism (the medieval philosophy known for asking questions about how many angels could dance on the head of a pin). If, at least in the minds of anti-religious progressives, that absurd and irrational philosophy could dominate the elite universities of Europe for centuries, what is their guaranty that an equally absurd and irrational philosophy will not begin its own reign in our day?

I’ve got serious misgivings with the way “privilege” is often used in political discourse these days, where the assumption is always that it’s racial, gender, or other forms of privilege that matter most. It’s not in any way that I deny that these forms of privilege exist, but the discussion is too simplistic and too myopic. Privilege is not absolute. It’s contextual. And race and gender and sexuality and other identity-based forms of privilege aren’t the only forms that exist. They aren’t even the most important. More important? The privilege of coming from a stable, two-parent, biological family, for one, and the privilege of a low ACE-score for another.

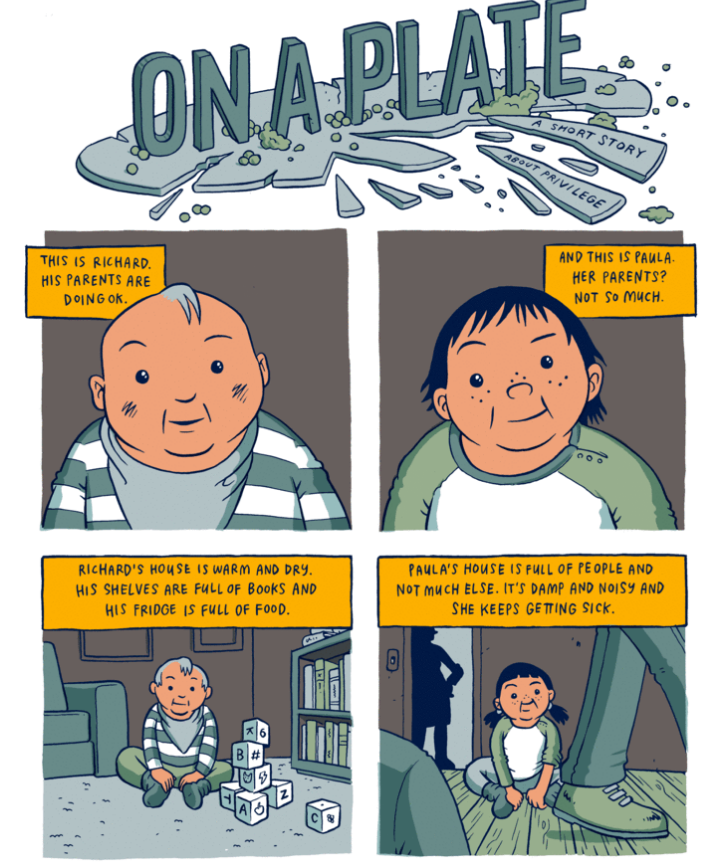

So, although most of the folks who share this comic (and possibly the author, too) would probably disagree vehemently with me over the topic, I share it because it’s actually a very, very good example of how privilege really works:

What’s really good about the comic is that it actually illustrates specific examples of privilege and, in this case, the privilege of class. The two children both have strong families, are both white, and gender doesn’t focus prominently in the storyline. Instead, it’s all about who can afford to study while in college vs. who has to shoehorn studies and menial work into the same schedule.[ref]Been there, done that.[/ref] It’s also about who has family connections that can smooth the transition into a competitive job environment, and who has to figure things out on their own.

Class is a better framework for discussing privilege than race or gender (although race-based and gender-based privilege do exist) because it gets closer to the heart of the matter: power. The trouble is that Americans don’t really like class. We’re not sure what it means and we kind of like to pretend it doesn’t exist. No one is more keen to pretend that class is not an issue then the upper-class, of course. This is one reason for the fascinating relationship of brand prominence to price.

Today, anyone can own a purse, a watch, or a pair of shoes, but specific brands of purses, watches, and shoes are a distinguishing feature for certain classes of consumers. A woman who sports a Gucci “new britt” hobo bag ($695) signals something much different about her social standing than a woman carrying a Coach “ali signature” hobo ($268). The brand, displayed prominently on both, says it all. Coach, known for introducing “accessible luxury” to the masses, does not compare in most people’s minds in price and prestige with Italian fashion house Gucci. But what inferences are made regarding a woman seen carrying a Bottega Veneta hobo bag ($2,450)? Bottega Veneta’s explicit “no logo” strategy (bags have the brand badge on the inside) makes the purse unrecognizable to the casual observer and identifiable only to those “in the know.”

One function of this kind of invisible prestige (although not the only consideration) is that it allows the most privileged to avoid attracting attention from those who are less privileged. Only their fellow elites can recognize their subtle status cues. This is also the reason that identity-based privilege is so appealing to middle- and upper-class Americans: it obscures more privilege than it reveals by quietly taking class off the table. Identity-based privilege is loud and boisterous, but it poses a negligible threat to existing socio-economic power structures. It’s about as revolutionary as a Che Guevara t-shirt.

Jonathan Chait just wrote an article about the new political correctness that is absolutely required reading for anyone with any interest in modern American politics: Not a Very P.C. Thing to Say. The hardest part of me writing about it is that there are just too many quotes that I wanted to include! I’ll try to hit the highlights, but this is really an article you’ve got to read for yourself all the way through.

So, note on the subtitle “How the language police are perverting liberalism.” Chait is here referring to the old-school definition of liberalism as being concerned with individualism and civil liberties. He notes that this is actually distinct from the political left (a statement that veers between accurate and quaint). True liberals don’t buy into PC, but the left has been influenced by Marxist ideas that discount the notion of free speech entirely:

The Marxist left has always dismissed liberalism’s commitment to protecting the rights of its political opponents… as hopelessly naïve… Why respect the rights of the class whose power you’re trying to smash? And so, according to Marxist thinking, your political rights depend entirely on what class you belong to… The modern far left has borrowed the Marxist critique of liberalism and substituted race and gender identities for economic ones.

He absolutely gets that the fundamental, driving motivator behind political correctness is not actually a concern with fairness or social justice, but a love of a particularly vicious approach to politics in the 21st century. He writes that “political correctness is not a rigorous commitment to social equality so much as a system of left-wing ideological repression” and also:

Political correctness is a style of politics in which the more radical members of the left attempt to regulate political discourse by defining opposing views as bigoted and illegitimate. Two decades ago, the only communities where the left could exert such hegemonic control lay within academia, which gave it an influence on intellectual life far out of proportion to its numeric size. Today’s political correctness flourishes most consequentially on social media, where it enjoys a frisson of cool and vast new cultural reach. And since social media is also now the milieu that hosts most political debate, the new p.c. has attained an influence over mainstream journalism and commentary beyond that of the old.

Chait also makes a simple but profound observation about the new political correctness: “It also makes money.” It does this (to summarize) as a near-endless supply of tantalizing clickbait. The effects of this new political correctness–far more virulent than the old version that peaked in 1991–is truly disturbing, and this is where Chait makes some of his strongest arguments as he describes thinkers on the left who have been cowed into silence by the new regime. Here are some snippets without context to give you some sentiment for how people react to living under the constant threat of being ostracized and publicly humiliated for thought crimes:

Just to be clear, these are all quotes from people on the left of American politics. They are feminist academics and liberal journalists, and they are afraid they will be turned on by their own. As events like Gamergate show, they should be afraid.

Chait tries to leave us with a happy note, sort of, but it’s not much to go on. He says that “the p.c. style of politics has one serious, possibly fatal drawback: It is exhausting.” The hope, as far as I can tell, is that the tyrants will just get tired of all the effort of maintaining their intellectual tyranny. And there have definitely been moments in recent news when it seemed as though the entire social justice movement was about to dissolve into a round of catastrophic cannibalism.[ref]The biggest one was the chaotic death-spiral / victim olympics after a feminist video about cat-calling went viral. Examples of conservative glee here and here.[/ref]

It would be nice if the social justice movement self-destructed. There are definitely some deep tensions within the movement, for example between cis- and trans-women. When the Vagina Monologues gets shut down not by annoyed social conservatives but by trans-advocates who feel that it discriminates against women who lack a vagina, you start to realize the potential for a major civil war.

So yeah: it would be nice if social justice warriors just got exhausted with the labor involved or if the coalition fragmented into warring sub-tribes, but if that’s the best plan to protect democracy and civil liberties and the culture of open inquiry then we’re already in a very, very dark place.

But hey, if you want to end on a less grim note, there’s this: Army Deletes Tweet About ‘Chinks In Armor’ After People Cry Racism. Anyone with a large vocabulary can enjoy the fireworks when someone inadvertantly uses a word that sounds offensive but (if you are suitably literate) isn’t. Like when a student in my high school English class complained that heroin was a sexist name for a drug because it put female heroes in a bad light. She didn’t realize that they aren’t the same word: heroin vs. heroine.[ref]And I went to a school for the gifted![/ref] Of course, it’s less funny if you’re the guy who inadvertently uses an unusual word in the correct way and gets fired for it,[ref]like those sad saps who used the word “niggardly” in the 1990s.[/ref] but we’ve got to find some humor in the situation or we’re all going to go insane.

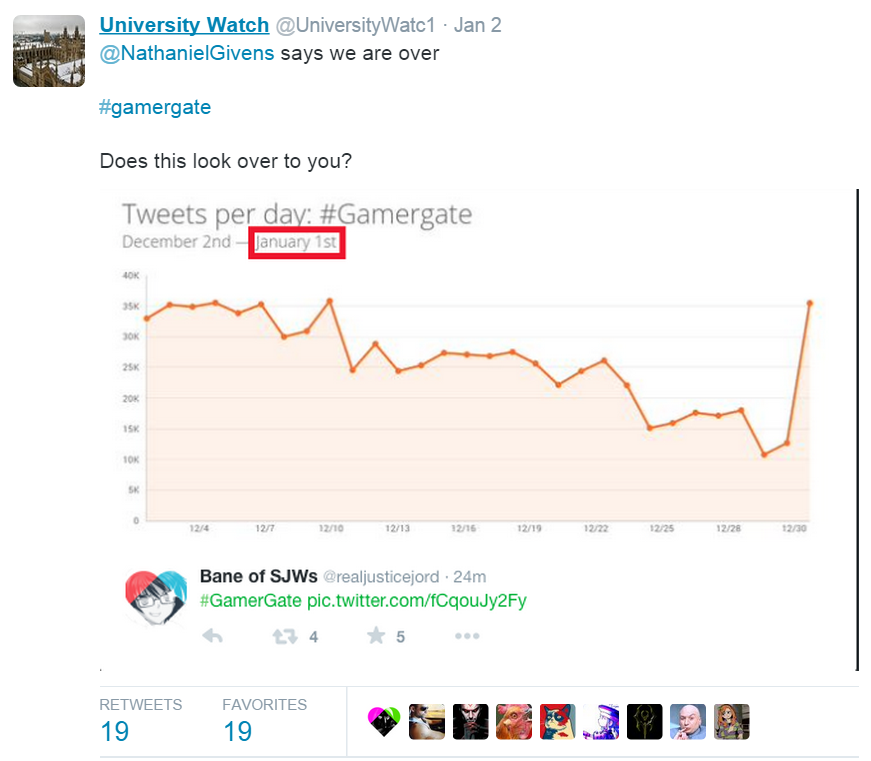

I forgot to mention that First Things ran a piece I wrote on Gamergate last Friday: Gamergate at the Beginning of 2015. I was pretty proud of the twin analyses I did for that piece, one explaining the reason for the radicalism of the social justice movement and the other explaining the tensions in the gaming community as it reacts to being mainstreamed. The loudest response to the piece so far, however, has been from Gamergate supporters who really don’t like that I wrote the phrase “Gamergate is dead” in the article.

I can understand their anger and, based on the Topsy charts they provided, they might have a point. It’s possible that I (and the folks I talked to) were premature in writing the movement off entirely. That would not be a bad thing at all in my book. There are times when you hope that you’re wrong. This is one of those times.