Last week I wrote a couple of posts about the Hardy Boys and magical ponies, although actually they were about marginal vs. average and statutory vs. effective taxation. Today, we get to the good stuff: how much more should the rich pay? It makes sense to start, however, with how much they already do pay.

What I learned in grad school, and what you can also read about on Wikipedia, is that in the US we already have a mildly progressive effective income tax system. So, when measured in average, effective taxes, the rich pay a bigger percentage of their income in taxes than the poor do.

This is actually a ridiculously hard question to answer definitively, and so it remains controversial. It starts with the fact that the rich have higher marginal rates, but they also have accountants who are good at finding deductions. Then you can go crazy trying to account for all kinds of tricky issues like double taxation or the value of the public services consumed or illegal tax evasion. In the US, where we have very rigorous privacy laws for income tax data, it will always be something of a mystery. (As an interesting aside, Nordic countries actually pay income taxation publicly–so that you can know exactly how much your neighbor made–and I sort of like that idea.)

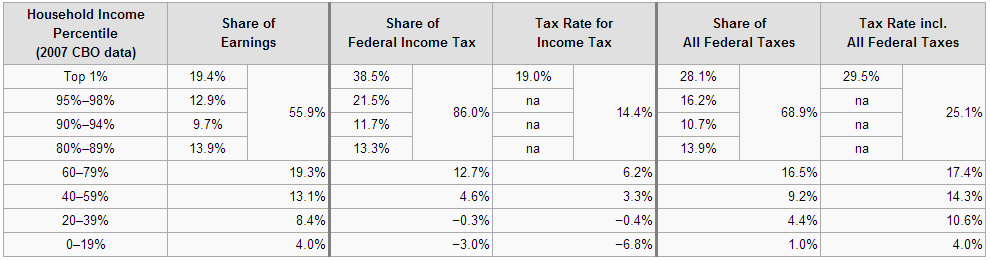

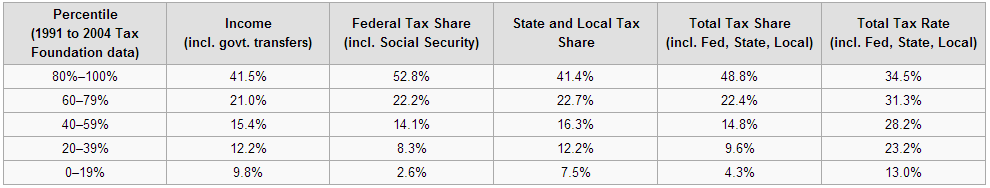

So if you checked out that Wikipedia link, the last two tables are the ones that are the most relevant. The first one, from the Congressional Budget Office, estimates the tax rate of the poorest 20% of Americans at 4% and the richest 20% at 25.1%.

The Tax Foundation (also non-partisan, but not a government agency like the CBO) did their own research and came to different numbers that tell the same story.

Because it’s such a complicated question (which may itself surprise people), I have met lots of folks who insist that the rich pay less in taxes than the poor anyways. This is a lesser-known variant of “mind over matter” known as “mind over facts”:

All the serious research I’m aware of boils down to variations on the theme of the rich paying more as a percent of their income, however, and so any serious conversation has to at a minimum start with the accepted fact that the rich pay at least as much as the poor and go from there.

Of course there are some outliers: Mitt Romney’s a rich American and his tax rate was about 14% in recent years. Slate did a pretty good job of explaining this in an article about capital gains taxation with the headline: Why Mitt Romney’s Effective Tax Rate Is So Low And Why It Probably Should Be. The short version is that if you tax capital gains like you tax income, our economic growth would take a serious hit. It’s also worth noting that folks like Romney or Buffet who make the living on capital gains (as opposed to salary and bonuses) are in a tiny minority even among the very rich, which is why the overall tax rate for the top 1% is still so high. Back in the early 1900s we had a genuine class of fat cats, but heavy taxation starting with the First World War eroded that social class until very little remains. The rich of today are “working rich”, which means their income is from work they do (salary and bonuses) rather than merely from living off of a huge pile of assets.

So the groundwork has been laid: we understand the basics of taxation and we know the rich already pay more. However, our economy is in trouble, our country is in the Great Recession, our debt has skyrocketed, and we’re running major deficits. Should the rich pay more? Yes or no?

This answer may seem like a bit of a cop-out, but stick with me: I really don’t care. Why? Because it’s a futile question that misses the point.

First of all, it’s futile because there’s no objective basis for an answer. Theoretical tax research uses models that are so simplified they have very little to do with the real world, and yet are still so complicated that there’s no consensus among economists as to what the rates should look like. Way back in the 1960s the Beatles were quite irate about their taxes, and they wrote a song about it:

You might have thought the lyrics (“Let me tell you how it will be / There’s one for you, nineteen for me”) were just poetic license, but in fact, that’s the actual top marginal rate the Beatles were paying at the time: 95%. Not to be outdone by anyone, for a while in California the top marginal rate was more than 100% (combined federal and state). During this time period an economist named James Mirrlees more or less invented the field of “optimal taxation theory” and concluded (to his surprise, he was a socialist at the time) that the optimal tax rate was about 35%. I’m a little rusty, but the gist of it was that any tax rate over 35% would do more harm than good. (The Laffer Curve is the same idea.) It was in the wake of that research that Thatcher and Reagan began their major overhauls of their respective tax regimes. (In the US the reforms culminated in the Tax Reform Act of 1986.) By playing with the assumptions, folks in more recent years were able to get the top rate back up to about 40-50% (in their theoretical models), and conservative economist Greg Mankiw linked to a debate just a couple of weeks ago about a new paper that pegs the top rate at 73%. In other words: no one knows that they’re talking about.

And yet you wouldn’t guess that from the way that President Obama and Speaker Boehner are going at it tooth-and-nail again, just like they did before the election. President Obama believes the rich should pay their fair share (whatever that means), but he doesn’t actually care so much about the money. If he did, he’d be willing to compromise with Speaker Boehner’s plan (formerly Mitt Romney’s plan, formerly every economist everywhere’s plan) to increase tax revenue by getting rid of loopholes or limiting deductions. This would increase the effective rate of taxation, bring in more revenue, and make our tax code a little simpler. So why doesn’t President Obama go for it? Because he’s trying to score political points, not balance the budget. (While we’re at it, no amount of taxation can compete with rising entitlement spending due to medical costs in the long run. Taxation is a sideshow comapred to the real financtial threat this country faces.)

Don’t let these harsh words persuade you that I’m in Grover Norquist‘s camp, however. He of the infamous “Taxpayer Protection Pledge” is a discredited anachronism. In the 1980s Republicans believed that if you restricted government spending you could achieve libertarian/conservative goals of limited government. The strategy, called “starve the beast,” was a failure. Instead of reducing government spending, the reduced tax revenues just converted the federal diet from tax revenue to borrowed (or, in the Great Recession, printed) money and the beast grew as never before. Norquist is coasting along on the momentum of a failed experiment that died three decades ago, and it’s a horrible condemnation of the GOP that they haven’t come up with a new plan since then. The GOP’s staunch anti-tax rhetoric boils down to nothing but empty posturing. Just like the Democrats.

Both the Democrats and Republicans seem to be playing the American taxpayer for fools. If you want to know the best way to collect a given amount of revenue: just ask an economist. This is not a hard question, and they will tell you. The consistent mantra is “lower the rates, broaden the base” which means to put an end to loopholes and deductions instead of playing with the rates more. Unfortunately the most recent proponent of this realsitic, sensible plan was Mitt Romney and, as Democrats will happily remind you, he lost.

But that only tells you how to tax. If you want to know how much to tax, don’t ask an economist. It’s not that it’s a hard question, it’s just not a scientific one. It’s a values-based question. “How much money should the government spend?” is a proxy for “What’s the proper role of government?” Good luck solving that one with a committee or a panel of experts.

And that is the second point that the question “How much (more) should the rich pay?” misses. Not only is there no way to objectively answer this philosophical question, but there’s also no sensible way to separate how much the government should raise from the question of how much the government should spend. They are two halves of the same coin.

Maybe in the end it’s actually not fair to berate the two political parties for their total failure to compromise and behave like adults. What we’re dealing with is deeper than just self-serving politicians. It’s more than just a frightening level of ignorance among the electorate. There’s a total impasse between two competing visions for America. One says “We, through government, can do more to help those in need” and the other says “Government already does too much”.

The crucial observation is that both sides are correct. The real crisis is that blind partisanship has got the two parties locked into a death-spiral that threatens to take the country with it. The us-vs-them mentality of Americans rooting for “their guys” is preventing the kind of genuine innovation that could help us break through the deadlock. It’s not going to happen based on some clever re-arrangement of the Republican or Democratic pieces currently on the board: we need to change the game.

And that’s one of the things I’m going to be writing about here quite a bit in coming weeks and months. There are solutions to these problems, but the current political players are incapable of reaching them.

Good post. Your writing seems pretty objective. I like that. Also you explain things very clearly for us laymen who don’t know much about taxes.

>There are solutions to these problems, but the current political players are incapable of reaching them.

Hey, something we agree on!