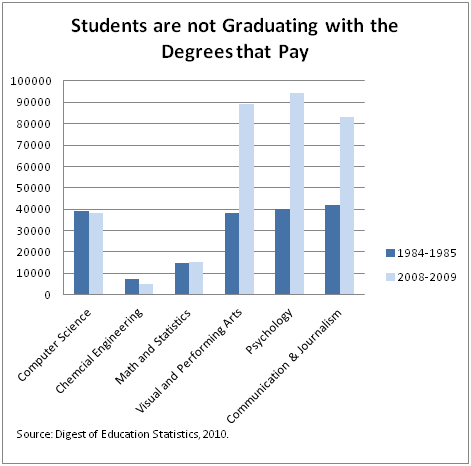

Take a look at the chart, folks.

It’s an old chart from a Marginal Revolution post back in 2011, but WalkerW (who comments here at DR) just showed it to me the other day. And I mean, come on. We’ve got less comp sci grads, but we’re doubling down on Visual and Performing Arts, Psychology, and Communications & Journalism? Who are these people, and what do they think college is for? The idea of a liberal arts education–that you go spend four years living the life of the mind–is quaintly romantic I suppose, but it’s also (in no particular order):

- Dangerous

- Elitist

- Deceptive

It’s dangerous because, with easy availability of loans, everyone wants to go. And as quantity demanded increases, so does the price. This means that all those folks going to get a legitimate degree have to pay more because their tuition is chained to the tuition of all those lemmings who think of college as a rite of passage rather than an investment in human capital. And, to forestall the horde of unemployed humanities majors with nothing better to do than staunchly defend the virtue of Art and the Noble Human Spirit on dar Interwebs, let’s get to #2: elitism. Spending 4 years reading Proust or Joyce before you go to law school sounds very romantic, but for a lot of kids college isn’t a way to maintain the status they were born in, but to claw their way up the social ladder. Waxing poetic about the glorious idealism of liberal arts education is well and good for the upper-middle class, but it’s the same kind of patronizing cluelessness that likes to bemoan the loss of manufacturing jobs that you would never in a million years consider working yourself. For some college might be an affectation, but you’re making it more expensive for those who actually need the degree and the skills so that they can have an alternative to driving a forklift if they so desire.

Which brings us to #3: deception. First of all, most of those humanities majors aren’t actually reading Proust or Joyce and we all know it even if no one will admit it. The real reason upper- and middle-class Americans go to college is to get wasted early and often. Which makes college something like the world’s most expensive and least exciting amusement park.

To be perfectly clear: I think there actually is great practical value in the humanities (I know I wish more business people knew how to write) and I also firmly believe that art doesn’t need to be practical to be valuable. But I also think that it’s a little bit silly to get a degree in something that’s not practical if you’re borrowing money to do it. And, as tuition prices are linked, that silliness has extreme negative externalities. I had to pay more for my education–which I picked with an eye towards ROI–because of all the folks rushing to get a 4-year degree in, like whatever because they can.

(Alternate title for this post: In which I rant at humanities majors. It’s OK, folks. It’s out of my system now.)

If we want to boost our economy with education, we need to provide incentives to get people to study subjects that will be good for our economic growth and for their standard of living. You could argue that it’s not all about money, damnit, and that helping kids get degrees in visual and performing arts has intangible benefits for society. Even if that’s right, however, the current structure of our program is such that government doesn’t actually pay for people to go to college. It just guarantees their debt, in part by making it impossible to discharge student loan debt in bankruptcy. What part of suckering a teenager into wracking up $100,000 in student loans to master method acting fulfills this romantic vision of a liberally educated society, again?

Personally, I abhor the very thought of college-as-job-training. Higher education does not exist to prepare you for a job. Higher education exists for precisely the elitist, navel-gazing purposes liberal arts majors list: personal development, the furthering of the human pursuit of knowledge, enlightenment, etc. It exists for people who enjoy learning for learning’s sake, and those are the only sort of people who should go to college .

I have no idea why employers would higher someone with a college degree over someone without one. The current arms-race escalation with education is going to keep going until you need a Ph.D., three post-doc positions, and at least 20 citations in the academic literature before you can expect to be a manager at Starbucks. It’s stupid and a waste of human potential, for all those years that people who just want to get a job and raise a family like normal people are wasting in useless education that means nothing besides building a resume.

So I disagree with your post for presenting the very idea that the purpose of college is to prepare people for the work place. The purpose of college is to educate people, and if people don’t want education after high school then they shouldn’t go to college. People who want to get ahead in life should be able to do so through hard work, certification training, or vocational schools. Keep college for elitist pricks like me who want to learn for the sake of learning, and don’t want the clutter and reduced standards that comes with the universal requirement of college attendance.

Thats my vehement opinion, anyway. The current attitude of college-as-job-training is ruining our lives and needs to be stopped, not further supported.

Given that hard sciences side looks for be fairly static, relative to the humanities, is it plausible that the increase in the humanities is driven by classes of people who traditionally weren’t statistically likely to go to college and not upper class naval gazers? It’d be interesting to see this broken down by other factors like income, class, 1st generation college students etc.

I kind of agree with both the post and with Reece. I think we need to reconsider a) why we go to college and b) the cost and find a better way. I do think wracking up six figures in debt for a degree in sociology (the norm for our society) is just irresponsible for most (the exception, of course, being those truly meant to be sociologists). We need to teach kids to really think about what they want to do as a career. And not just “what interests you most?” but also, “What kind of lifestyle do you want to lead? Do you want to have a flexible schedule? Have time for kids and a family? Do you need to make a certain amount of money? What hours do you think you’d like to work? Do you want to be a hard-driving, long-hours type career person?” I feel like high school grads are woefully unprepared for the realities of the working world and often even worse off after attending college where responsibilities are at an all-time low and partying is at an all-time high for 4 long years. The fact that this is the NORM in our society is just messed up (and the fact that it wracks up the price for serious students is unjust).

But I also agree that we need to revisit the days when a 4-year college degree wasn’t a requirement for most professions. So much can be learned on the job or through apprenticeships and certifications… often times MORE can be learned this way. And one aspect of our 4-year-useless-liberal-arts-degree system that drives me mad is that it bleeds into these more technical professions in irrational ways. For example, often times even IF a person gets a 4-year degree (a practical one!), if they want to change directions in their practical career a few years down the road, well, employers shut them down because they don’t have the 4-year-degree in THAT area… so they need to either go back to school for another 4-year-degree (ridiculous), try to get an unnecessary master’s (which typically requires another set of hoops to jump through and some extra undergrad coursework), or give up or try to find a rare opportunity to gain experience that will be viewed as equivalent to the “right” 4-year-degree.

Another issue I see is that it’s not just that the students aren’t studying Joyce in their liberal arts degrees… it’s that a lot of the classes offered today just aren’t bothering to teach much Joyce. There are so many throw-away courses at Universities. We’ve lost sight of higher education as being a truly “high” endeavor because the schools themselves have lost a lot of credibility. Lib arts classes are more political and shallow than steeped in classical liberal arts education. So even if engineers could benefit from a class in Shakespeare or Grammar to broaden their horizons, chances are, they are only required to take electives like “Vampires in Literature” or “Psychology of Food.”

“I have no idea why employers would higher someone with a college degree over someone without one.”

Because they’re lazy, ignorant, incurious and shortsighted. What’s worse, it’s probably a lose-lose proposition for both the employee AND the employer: http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/06/why-is-it-so-hard-to-hire-great-people/277122/#disqus_thread

Wharton’s Peter Capelli has done some excellent work on the topic: http://www.forbes.com/sites/knowledgewharton/2012/06/22/242012/

I’m afraid Nathaniel will disagree with me here on principle, and maybe such a system already exists, but I’d like to see experimentation with federal aid/grants/research dollars being tied to repayment outcomes.

I’m not entirely sure about the mechanism, but perhaps, as a stick, an institution takes a share in the underlying loan portfolio of its loan/grant-receiving students. Or, as a carrot, it’s given some portion of the interest from government-backed/funded loans if (and only if) certain cyclically adjusted debt-to-earnings targets are reached.

Consider that from the Ivies to the land-grants, Wall Street is no longer the most revered destination of choice. Rather, it’s Google, Apple etc. I personally know a number of people who studied art as undergrads at VCU and now work as designers for Google, Apple, Nike etc. I also know a number of people who majored in maths and econ and went to Parsons for a masters or professional degree because they wanted to build apps instead.

I suspect a large portion of the rise in Visual and Performing Arts/Communications & Journalism is driven by an increase in subcategory degrees such as graphic design, web design, “instruction in computer and telecommunications technologies and processes; design and development of digital communications” etc….

http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/cipdetail.aspx?y=55&cipid=89300

http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/cipdetail.aspx?y=55&cipid=87221

What’s interesting is that undergraduate lifetime earnings for Communications Visual and Performing Arts don’t differ all that much from generic Liberal Arts or even Business: http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/acs/infographics/index.html

I like both of these ideas:

“A serious student-loan fix would change this incentive. First, federal aid could be capped, perhaps at a national average, or simply indexed to the consumer-price index, making it harder for schools to raise tuition willy-nilly. Second, schools that receive subsidized loan money could be left on the hook for a percentage of the loan balance if students default. I would favor allowing students who can’t pay to discharge their loan balances in bankruptcy after a reasonable time—say, five to seven years, maybe even 10—with the institutions that got the money being liable to the guarantors (i.e., the taxpayers) for, say, 10% or 20% of the balance.”

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324688404578541372861440606.html?mod=wsj_share_tweet

I also like Noah Smith’s idea for scaled, cheap federal universities, but I see you’ve already commented on his post so I won’t waste time linking! :)

Reece-

That’s a really loaded way of phrasing it.

Something that people who pine for the days when college wasn’t required don’t seem to understand is that our world is changing. We’re becoming a knowledge-based economy, and that’s not just some buzz-word. We’re also becoming hyper-specialized.

The real value of college is not necessarily that you learn some skill which you then perform in your job. That’s what trade-schools are for, and I’d like to seem more of them and more respect for them.

No, what college really teaches people is how to learn. And there is no more valuable skill for the 21st century than the ability to quickly master new and difficult material. And that is something you learn much, much better in a STEM class than in a humanities class for the simple reason that humanities are easy to BS. There’s no objective standard of right/wrong, and so the level of rigor is just really pathetically low.

I guess another way of phrasing this is that a humanities major might be worth something in today’s economy if it wasn’t so damn easy to get. Between politics, grade inflation, and the subjective nature of the discipline the bar is just way too low on anything that doesn’t have an objective basis.

That’s a Luddite opinion. With every passing year, it takes more and more to be able to contribute to the economy. You could be a serf with zero education. You could be an independent farmer with only basic literacy and arithmetic. You could be a salesman with a high school education. To get a legit job in the 21st century? To be a manager in a complex organization with serious financial operations and almost invariably some connection to high-growth tech? You need to know how to learn, learn fast, and learn hard things. You really do need college.

And yes: by this argument in the 24th century everyone will need to have PhD. The trend gets worrisome at some point, but it makes sense. The more complex our world becomes, the more training we need to be able to add something to it.

Pining for the days when a 4-year degree was optional makes as much sense as pining for the days when anything past elementary school was optional.

Sarah-

I think you make a good point: right now we’re sort of shoehorning a 4-year liberal arts tradition to meet a need for greater training, but it would make more sense in a lot of cases to rehabilitate trade schools. I think a lot of really important jobs–like software development and high-skilled manufacturing–would benefit from shorter, more concentrated curriculum.

bazzagazzer-

You raise a really good point. Let me know if you find anything along those lines, I’d be curious.

thegalen-

That’s another really great perspective. Either of these two insights could really change the meaning of this data, but I just don’t know if that’s what’s really going on or not.

I think this post sticks it to undergraduates a little too harshly. How about the adults, the professors, the career counselors – the people with actual real-world experience- who could have guided these kids toward more successful paths? I’ll admit I am one of those naïfs who picked a squishy major (history – following the “do what you love” advice dispensed universally) (anecdotally I was also a first generation college grad, from a low income household, FWIW) but I was reassured many times that there were lots of prospects for people with my major since employers appreciate someone who can write. I fully expected my degree to be less lucrative than a business degree, for example, and that the prospects would be fewer – I didnt expect my degree to be essentially worthless and my prospects non-existent. I’m not so romantic that I wouldn’t have listened if someone had sat me down back then and said as much. (I did graduate before the economy went to pot in 08, so no one was saying that though.) One last observation – these are all 08/09 grads, who again would have chosen their majors back in the halcyon pre-crash days. I would be more interested in tallies of humanities majors among 2012/13 grads.

A little on business majors:

http://theslowhunch.blogspot.com/2011/08/moderately-intelligent-man-of-business.html

“That’s another really great perspective. Either of these two insights could really change the meaning of this data, but I just don’t know if that’s what’s really going on or not.”

This is indeed the case, at least in regard to the coding. The underlying data used by Tabarrok can be found here: http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2011015

He relies on the 2-digit CIP which lumps Industrial Design in with Dance:

http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2002/cip2000/ciplist.asp?CIP2=50

This is, obviously, deeply problematic for institutions like Parsons or Cincinnati or even VCU. The majority of my friends who graduated with art or design degrees from these institutions work for places like Google, Tumblr, Apple, Nike, Disney and various and sundry startups between Richmond, DC, NYC, SFO and LA. Very few are artistes in the traditional sense.

Another thought: maybe you can explain why I’m wrong on the economics, but intuitively it seems that if humanities and arts degrees are worth less, and STEM degrees are worth more, then students paying current rates for the former are subsidizing the latter where credit hours cost the same across degrees.

Thanks to the legion of marginally employed humanities and arts degree holders, these courses are cheaper to teach and to TA (STEM professors get grant-funded RAs). It’s also obviously cheaper to physically equip a university to teach creative writing than it is to run a proper Chem or Computer Science Lab.

It’s true that a lot of STEM departmental money comes from grants, but STEM students take plenty of non-grant funded Gen Ed courses, and with more people attending college cuts to *total* university funding are necessarily unpopular (http://www.people-press.org/files/2011/02/702-41.png)

Then there’s reduced unit cost of things like physical plant operation, grounds maintenance, etc., that’s made cheaper via scaling thanks to all the non-STEM attendees.

Lastly, there are the agglomerative benefits of STEM students being surrounded by non-STEM material and students (e.g. Zuckerberg meets the Winklevii). I suspect that STEM material is less accessible to non-STEM students as compared to STEM students and non-STEM material.

Maybe you paid more for you degree than you otherwise would have, or maybe not!

“And that is something you learn much, much better in a STEM class than in a humanities class for the simple reason that humanities are easy to BS. There’s no objective standard of right/wrong, and so the level of rigor is just really pathetically low.”

I’m rather sick of the “anything goes” approach to literature which is invading spheres such as history. A big tragedy is that reading, actually reading the text and engaging with it, is a lost art.

I agree with the post and with everything everyone has posted (well, you know, for all intents and purposes). And also this:

The problem with graduating a lot of psychology and music majors isn’t that the world doesn’t need psychologists and musicians, it’s that the world doesn’t need THAT many of them. The US tends to import chemical engineers (and chemical engineering students) from other countries. That has a lot to do with poor math and science education in the US. There are steep barriers to entry in most STEM degree programs, and the most obvious one is required advanced math classes. So for the washouts, the kids who don’t cut it in college calculus, etc., what then? Well, a degree in something is better than a degree in nothing, right? And so schools just keep growing their humanities and art and social science departments and graduate many many times more theater technicians than there will ever be theater technician jobs, and then they hit the street to protest that their dreams were stolen, that they should be given a job to pay off all the debt they’ve been burdened with, because they should make more money as college graduates than, say, Edward Snowden with his GED.

And people DO expect to make more money as college graduates. They constantly hear that people with college degrees earn more money than those with only a high school diploma. This line is repeated to school children and their parents. Education (more than entrepeneurship, hard work, or anything else) is held up as the means of upward mobility. “I was the first in my family to go to college” is a statement heavy in significance. It is significant to the individual family and often to a larger community the individual comes from (immigrant, inner city, rural, minority, etc.). And it is true that people with college degrees earn more money, on average, than people without college degrees. Of course, correlation is not causation, and there are several nuances and caveats at play. For example:

1) Timing the market — boom times are better. If I hadn’t served a 2-year mission, I would’ve entered the job force at least 2 years earlier (in fact, more than three years, since I worked for a year and a half to pay for it). I would’ve been looking for a job at the height of the dot-com bubble instead of the end of it. College grads will be better off when the job market is tighter. How to hedge that? Get a more valuable set of skills (like you say).

2) Some jobs require a degree. Some high-paying jobs (or at least better-than-average-paying jobs) require a degree because of professionalization. Doctors, nurses, accountants, architects, lawyers, pharmacists, etc. cannot legally practice in most states without professional education, training, and certification. Some professions (e.g. cosmetologists) do not require a four-year degree in most states, but many professions require at least a four-year degree. Also, many public-sector jobs (teachers, public administrators, etc.) not only require degrees, but pay more based on education.

3) Some jobs don’t require a degree. Software developers do not require a degree to legally work in this country. Neither do system administrators, or web designers, or sales executives, or comedy writers. Experience, expertise, portfolio, etc. Those things matter most for these jobs. So Snowden gets paid the big bucks cuz he can do things that a schlub with a Master’s in history who’s working at Barnes and Noble doesn’t know how to do. Tada!

4) College is a class marker. For undergrads, college is one of the most expensive yet effective ways to be marked as a certain kind of person/employee. A high school diploma does not guarantee a person can read and write and speak and reason at an acceptable level of competency, but a college degree (at least from many schools, pick your favorite) does. By requiring a degree for a position (any degree, even an unrelated one), employers can find a “certain kind of person.” The Ivy League is one of the biggest filters. Wall Street hired humanities majors from Harvard at the peak of the bubble not because the grads had special skills, but because they could speak and act and think better — otherwise Harvard wouldn’t have let them in, never mind graduate them. Could someone from a school in, say, Virginia do just as well? Sure, but Harvard and Yale — that’s seen as a safe filter. Why does Teach for America hit those schools so hard? Same reason. They’re buying the brand.

So who is to blame for this sorry state of affairs? In my opinion, it is:

1) The federal government, for subsidizing a bubble in higher education debt

2) Universities and colleges and their guidance/financial counselors for ignoring the ramifications of graduating too many students (often with a lot of debt) in fields with few prospects

3) Secondary educators and their focus on education as the only means of upward mobility (As a side note, the Black middle class is disproportionately focused on the public sector, where educational attainment is more clearly tied to pay, than the private sector, where pay is tied more to value-add activity – sales, etc.)

4) Parents who don’t know any better

5) Kids who won’t listen to their parents who do know any better

More data from AEI: http://www.aei-ideas.org/2013/06/how-your-college-major-affects-your-employment-and-wages-in-2-charts/

Over at Business Insider, some argue that humanities lovers should just go for it: http://www.businessinsider.com/11-reasons-to-major-in-the-humanities-2013-6

And apparently the grade inflation in the humanities attracts would-be science majors: http://au.businessinsider.com/science-majors-and-grade-inflation-2013-7

“So who is to blame for this sorry state of affairs? In my opinion, it is:

1) The federal government, for subsidizing a bubble in higher education debt”

That’s not as interesting a question as what the costs would be otherwise. If we know that just SOME college (not even graduating) has better ROI than everything from real estate to stock holdings, increased lifetime earnings less decreased lifetime social safety net outlays makes the federal backing (even if it’s responsible for 100% of the blame on inflation) a pretty good deal on balance.

thegalen-

You realize that if government backing is increasing the price then rather than / in addition to providing expanded access to a high-return investment, government is actually decreasing the return, right?

Sure. There’s obviously a point (either through price inflation and/or degree devaluation) at which the collective return on backing goes negative. But so far it’s been a great deal!

The cost accountability problems ARE worrisome, so I’m happy to see policy innovation that doesn’t take a fire axe to an important channel for social mobility.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323823004578595803296798048.html

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323823004578595803296798048.html

— I’m reposting this. It’s not quite what this thread’s about I think, but it’s a phenomenal point, and really underlines the fact that college (the academy) has become all things to all people in many good and bad ways. But the main theme of this essay: that literature doesn’t need to be studied, it needs to be read, is beautiful and true.