So this article popped up in my Facebook news feed. It’s a post written by a young man who lives in my home town, is a dad to young kids, and is the sort of fellow who would go to a sci-fi book club. In other words: someone not unlike myself.

The similarities are deeper than that, however. He talks about the way he self-consciously parents to teach his children the meaning of consent with rules like:

While they are little, I’m trying to be the man who stops. If I am tickling my girls and they say the words “stop” or “no,” I stop. If they want me to start again, they have to tell me to. If they ask me to not hug or kiss them, I don’t. As they grow into teenagers, I want them to have an ingrained sense of what consent is and how people express it.

That’s almost an exact mirror image of decisions that I’ve made–probably for slightly but not entirely different reasons–as a father myself. I also stop tickling my kids whenever they say “Stop, please” and when my kids don’t want to give me a hug or a kiss I usually ask them very nicely, but don’t take one without their consent. I mean, I’m not weird about it, but I like them to have a balance of obedience (which I also emphasize) and autonomy.

So my setup is simple: this guy is a lot like me in a lot of ways. But when it comes to “the patriarchy”, everything goes completely off the rails. Here’s his story:

Recently, I was invited to join a science fiction book club that meets monthly at a pub about a mile from my house. Most of the folks in the group are parents, so we meet at 8:00 PM, allowing for family time after work. The night of the club, I helped put our youngest to bed and then told my wife, Kat, I was ready to walk over. She paused, clearly surprised that I would be walking–not because I rarely exercise,1 but because it was dark outside.

So, he gets to walk a mile on a dark city street. His wife doesn’t. That seems unfair, and it makes him mad. It makes me mad, too. It makes him mad at “the patriarchy.” It makes me mad at rapists. That discrepancy might not seem like such a problem at first glance, but it is a problem for me for two reasons.

First, I don’t like blaming some impersonal abstraction. It feels like a defense mechanism for guilt-avoidance.

Let me explain what I mean. The author states that “One in six American women have been the victim of rape or attempted rape.” and then asks his readers to: “Think of six women in your life.” The clear implication is that A – he doesn’t actually know which women in his life have been victimized and B – he doesn’t expect his readers to, either.

I don’t want to judge this author individually, but I think this fits a very, very widespread trend. You see it in movies (especially comedies) all the time: some dude spends his teenage years and/or 20s having sex with as many women as possible, then one day he has this revelation (usually because he discovers he has a daughter or something) that–gasp!–women are people, too. All those sexual conquests? Those were actually human beings!

What’s really revealing about this trope is what happens next, however. There’s always some stunningly attractive women ready to accept the boy-turned-man without any reservation. And all those women that he mistreated in the past? They either disappear entirely from the narrative or get one last cameo where they are depicted as either the butt of a joke or as being perfectly, totally, absolutely fine. (Sometimes both at once.) The surface message is supposed to make people laugh, but the deeper message is supposed to comfort and assuage the guilt of men who spent years objectifying women by telling them that decades of dehumanizing the ladies in their lives didn’t have any real consequences. The template for males in our society is to treat women like objects until you have a daughter, then laugh about it. Or, you know, blame the patriarchy, I guess.

The reality is that the time to start caring about the health and safety of the women in your life is (at the latest) your own teenage years. I have a hard time believing that anyone who was sincerely concerned for the girls in their social circle could go through high school and college without witnessing the awful toll of sexual violence for themselves. I don’t like repeating the stories (even anonymized) from my own past and hate the feeling that I’m in some sense bragging from what I’ve witnessed. But I’m also tired of remaining silent and thereby contributing to the overall notion that it’s OK for guys to objectify women until they grow up. It’s not. I just want to say that if you have to imagine the victims of sexual violence in your 30s WTF were you up to in your teens and 20s? Were you blind? And was it because you didn’t see the women around you as people?

That’s why I don’t like blaming “the patriarchy”. What is the patriarchy, anyway? It’s some nebulous academic abstraction or socio-political construct. Whatever it is: it doesn’t have anything to do with concrete reality. Along with the whole “imagine women who may have been assaulted”, it just makes me think of selfish man-boys who cared only about sating their own desires until one day they looked into the eyes of their newborn daughter and felt the immense weight of holding another human being and were suddenly forced to recognize the humanity of the women they had objectified for all those years. Rather than really face the reality of their past behavior directly, however, it’s a lot easier to blame some abstraction like “the patriarchy.” That’s much easier than, you know, blaming actual men. Young fathers who suddenly realize that women are people might not have raped or sexually assaulted any women in their lives, but deep down they know that the kind of objectification they engaged in was the first step down that path. And, more often than not, they have done shameful things themselves that they’d rather not think about. Keeping matters abstract helps them keep their guilt buried. “I didn’t know,” I imagine them saying. “Well, you should have,” is the only acceptable response.

Second, I really object to the fact that blaming the patriarchy can often end up enabling predators. He writes:

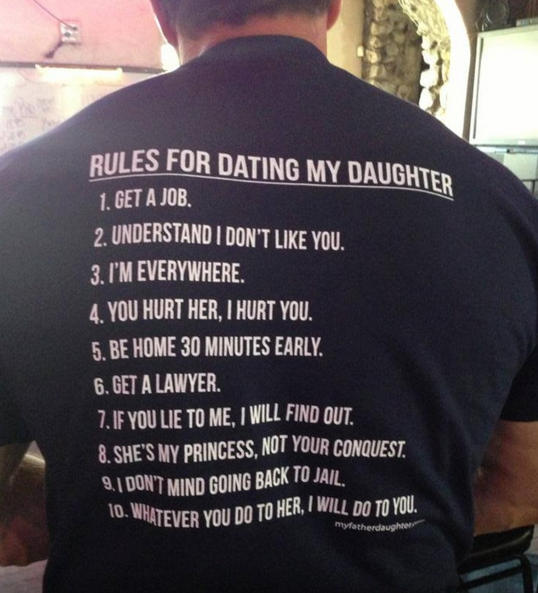

I am offended by “shotgun and shovel” dad jokes. I am offended by t-shirts like this one. I’m not afraid that my girls will have sex lives; I’m worried about the world that makes it an uphill battle for them to have a good one.

The clear implications here are that the only motivation anyone could have for trying to protect women is a deep-seated desire to control their sexuality. That may cut it as a thesis for an undergraduate essay, but it’s a pretty pathetic response to the actuality of violence against women. Men are overwhelmingly the aggressors against women (not “universally” but “overwhelmingly”) and you can try and blame “the patriarchy” but the likelier explanation is “the biology”. Men are bigger, heavier, stronger, and more motivated to have frequent sexual partners. Given this predisposition, one simple way to influence the number of sexual assaults is to mess with the degree of opportunity men have to exploit women. This means that things like a culture of sexual promiscuity (which makes sexual predators more or less impervious to legal or social repercussions) directly enables predators.

Even if only a tiny fraction of men are willing to abuse those facts to gratify their lusts (for sex, power, or both) staunchly attacking the other men who try to intimidate the predators strikes me as idiotic. I’m not saying that jokes about killing boyfriends are supposed to literally scare boyfriends into not raping girls, but they are supposed to uphold an expectation for decent behavior out of men. The idea is that men have to behave in certain ways if they want to enjoy the presence of women. It says, fundamentally, that men have to earn a shot at companionship. Note that I’m talking about duty not entitlement. I’m saying that there’s an expectation that men work hard to be worthy to ask a girl to go on a date (a request she can freely decline). I’m not saying that men who work any amount are entitled to sex. The two ideas–duty and entitlement–don’t go hand-in-hand. They are opposites.

When dads wear shirts like the one the author complained about (see above), it’s not because they want to oppress women. It’s because they want to protect women. The behavior he finds “offensive” is in fact designed to empower women by intentionally subjugating the superior physical power of men for the benefit of women. I’m not going to say that this has never been used as an excuse to control and dominate women or that we should just try to re-animate the corpse of imagined 1950’s society. But I am really tired of the idea that chivalry is exclusively or even primarily about dominating women as opposed to serving women, and of the idea that there’s nothing from the past that might be worth preserving and even strengthening in the future.

I also flatly reject the idea that believing women deserve protection amounts to believing they are weaker. The protection I’m describing is limited to physical protection from physical danger, and it implies only that women are (again, not without exception) physically weaker. If that implication bothers you: tough. You can also be bothered by the fact that the sky is blue.

Even more, if you think that “physically weaker” implies “less valuable” or “less human” or “weaker in some general, all-encompassing sense” than the problem is with you. If you think that we have to pretend women aren’t physically weaker then it’s too late: you’re already sexist. You already believe that a cluster of male-dominated traits (physical power) are in some sense superior. That’s what your denial really shows: your preference for physical power as a dominant trait. Denying that such traits are unequally distributed just makes you sexist and foolish. On the other hand, if you really sincerely believe that women aren’t physically weaker than I suppose we should just shut down the WNBA and all other female-only versions of sports and just see how many women make it in the NBA? No? Then you already know that women deserve special treatment to reach equality so stop pretending otherwise.

I’ll go even farther, however, and say that the notion that we can rank humanity on any metric at all is intrinsically offensive to me. I believe that the value of a human being is independent of the things they can and cannot do. All human lives are equally valuable. Period. Male, female, old, young, gay, straight, whatever.

I feel like the author of that post would probably like that last sentence. I believe that his heart is in the right place. But it takes more than good intentions to make good decisions. How did we get so apart, this fellow sci-fi aficionado and I? I don’t know, but I feel like we’ve got to start to bridge the gap or things are just going to keep getting worse for the women in both our lives.

Some extra thoughts since I first wrote this post.

First, I came across a seemingly unrelated post by one of the little people who danced with Miley Cyrus for her infamous VMA performance and regretted it. The post is called On Being A Little Person. In describing how her friends and family protected her from bullying throughout her life, she recounts this story:

Now, the majority of the people who I know that call themselves feminist would conclude this story by giving Chris, Mark, and James a tongue-lashing for trying to protect her. After all: the implication of protection is weakness, right? And the implication of weakness is lack of value, right? Wrong. The problem with that logic is that it relies on the idea that physical strength = value. Which seems like a pretty warped perspective, In any case, the post’s author draws a very different conclusion from this experience:

Having men jump to her physical defense didn’t make her feel disrespected. It made her feel respected. This is the essence of chivalry.

Second, one of my Facebook friends brought the Maryville rape case to my attention. He’s a father himself, and one of those “shovel and grave”-joking dads that the author of the original post I responded to (above), and this is a status he just posted:

The argument that this is really just a father’s expression of fear that his daughters will have sex lives is, quite frankly, disgusting. There’s something seriously wrong with a world that has lost the ability to understand that protecting the vulnerable is an honorable pursuit. And also that there’s nothing wrong with being vulnerable.

Thanks for this post! I hope not all chivalry is dead. My kids go to a school where the boys are expected to open doors for the girls. A different boy every week is assigned “door holder” for each class in the elementary years. The boys always line up behind the girls and must wait for them to go first. They are taught appropriate boy-girl behavior via Proverbs, stories, fables, etc.

Girls also have responsibilities within the classroom. They are not permitted to flaunt their special status. For example, they learn it is inappropriate to tease the boys about going first. They basically foster mutual respect between the sexes. I have heard my daughter complain that her older brother is “not being a gentleman” more than once :). I love this formation. Maybe we’re setting up our boys for some failure in a more feminist world, to be slapped for holding a door open, called sexist, or something. But I don’t care — Our kids should learn that boys and girls are different, but equally valuable, that there are appropriate ways to treat each other, and politeness and respect even extend into conversations among just boys or just girls. Thanks for trying to be an example too, Nathaniel!

Nathaniel, I’d be interested to know what you’d make of this idea–that “benevolent sexism” is appealing to some relatively unattractive characteristics of (some) women: http://www.rawstory.com/rs/2013/10/16/women-who-feel-entitled-more-likely-to-endorse-benevolent-sexism-study-finds/

Kristine-

My first reaction is that I’m not sure if that consideration is really actionable. I think it’s clear that any time a duty exists it not only can but will appeal to a sense of entitlement at the receiving end of the duty. Does that mean we should just eradicate the entire concept of duty lest we foster entitlement?

My second reaction is that I’m concerned with the specific construction of “benevolent sexism” in that article:

They way I read that is that any generalization about the sexes must be sexism of one form or the other. This strikes me as tantamount to defining gender essentialism as intrinsically sexist. I think that’s problematic.