Update: I wrote a follow-up to this piece: Further Thoughts on World Building

I just finished reading Brandon Sanderson’s monstrous tome: Words of Radiance. It’s his second book in the Stormlight Archives and, like the first, clocks in at over 1,000 pages. The expression on the clerk’s face in Barnes and Nobles when she picked up the book to hand it to me was priceless: “Wow,” she said as she nearly dropped the book, “This is a commitment!”

I’ve never liked high fantasy taken as a genre, but I did love The Lord of the Rings (which launched the genre) and I am enjoying Sanderson’s Stormlight Archives. Despite the fact that I’m enjoying them, however, they display the systematic problems that have plagued the genre ever since (but not including) Tolkien.

High fantasy, if you’re not familiar with the term, refers to the kinds of fantasy books that have maps in them. Not to mention a glossary, pronunciation guide, appendices, and maybe an index, too. This is because high fantasy is defined largely by its setting: an imaginary world with its own history, cultures, religions, languages, and—of course—magic.[ref]Close relatives of high fantasy include medieval fantasy and epic fantasy. The antithesis (within the fantasy genre) is urban fantasy like the Dresden Files because those books are located primarily within a recognizable version of the world.[/ref]

For all practical purposes, Tolkien invented high fantasy. Of course all the pieces came from Saxon and Norse myths and folklore, but what he created when The Lord of the Rings was first published in the 1950’s was something new. The books were very successful from the early years and have gone on to sell more copies than any other novel (150 million thus far) except A Tale of Two Cities.[ref]Tolkien proves he’s still the king[/ref] The corpus of high fantasy has been and continues to this day to be a long line of Tolkien imitators.[ref]This is starting to change with recent blockbusters like George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire and Patrick Rothfuss’s Kingkiller Chronicles

that emphasize created worlds but also depart from high fantasy conventions. Tolkien remains the paramount figure in the genre, however.[/ref]

The problem is that they have all learned the wrong lesson. They understand that setting defines high fantasy, and they understand that Tolkien’s mastery of world-building fueled his artistic and commercial success, but they fundamentally mistake the product (The Lord of the Rings as a narrative text) with the process (Tolkien’s actual beliefs and practices for world-building).

To correct this confusion we must start with the realization that Tolkien’s world-building was inextricable from his religious faith. He was a devout Roman Catholic and what we call world-building he called sub-creation, which is a term with obvious and deliberate religious connotations. As the Tolkien Gateway puts it:

‘Sub-creation’ was also used by J.R.R. Tolkien to refer [to the] process of world-building and creating myths. In this context, a human author is a ‘little maker’ creating his own world as a sub-set within God’s primary creation. Like the beings of Middle-earth, Tolkien saw his works as mere emulation of the true creation performed by God.

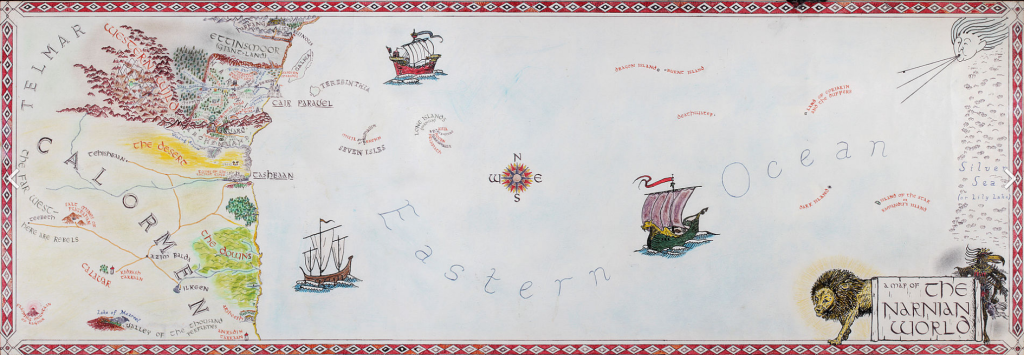

As we delve deeper into Tolkien’s theory of sub-creation, it is useful to contrast his view with that of his friend C. S. Lewis, as Professor Downing has done in a paper called “Sub-Creation or Smuggled Theology: Tolkien contra Lewis on Christian Fantasy” at the C. S. Lewis Institute. C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia certainly deserves mention as co-founding the subgenre of high fantasy and, for the most part, his reverence for the work of sub-creation paralleled Tolkien’s. But there were important differences, and those differences are very clear in the different tones and styles of the works and also in the supremacy of The Lord of the Rings over Chronicles of Narnia in historical and literary impact.

Downing points out that, for Tolkien, “engaging one’s creativity is an imitation of God and a form of worship.” For Lewis, by contrast, a work of art had to have a higher purpose than the creative impulse itself. In his famous essay “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to be Said,” Lewis propounded a dualistic account of artistic creation. The Author writes for the sake of writing, but The Man harnesses this impulse towards some external end. As Downing summarizes Lewis: “[A] writer can’t even begin without the Author’s urge to create, but… he shouldn’t begin without the Man’s desire to communicate his deepest sense of himself and his world.”

The Lewis-Tolkien dialogue on sub-creation is a particularly interesting one for a Mormon to enter because of theological differences over the term “creation.” As Downing notes, C. S. Lewis referred back to the orthodox Christian theology of creation ex nihilo in his discussion of artistic creativity. Lewis wrote in a letter to Sister Penelope:

‘Creation’ [as] applied to human authorship seems to me entirely misleading term. We rearrange elements He has provided. There is not a vestige of real creativity de novo in us. Try to imagine a new primary colour, a third sex, a fourth dimension, or even a monster which does not consist of bits and parts of existing animals stuck together. Nothing happens. And that surely is why our works (as you said) never mean to others quite what we intended: because we are recombining elements made by Him and already containing His meanings.

For Downing, this is a point against Tolkien. Tolkien stressed the independence of sub-created worlds but—as Downing and Lewis point out—there is no such thing as independent creation. Humans create by dividing or combining elements that are already available, not by making new elements. From a strictly orthodox Christian theological perspective, this is a fairly serious indictment of Tolkien’s theory of sub-creation because it draws a deep chasm between the kind of creation in which God engages and the kind of sub-creation in which we may participate. How can we be worshipfully imitating our Father when it turns out that the process in which we are engaged is actually a totally distinct process that only happens to share the same label by linguistic happenstance?

As it turns out, however, a rejection of creation ex nihilo is one of the defining aspects of Mormon theology. As many non-Mormon Christian theologians have also observed the Creation (as depicted in Genesis) is almost exclusively a depiction of creation the way that Tolkien and Lewis and all other writers create: by re-arranging pre-existing materials. After “let there be light,” God’s work is all about separation: light from dark, sea from dry land, and so forth. He doesn’t seem to create the earth, moon, stars, sun, or anything else by calling them into being out of the void, but rather by molding unformed materials. For a Mormon like me, at least, sub-creation is more akin to the Creation of God, not less.

In any case, however, what really matters is that Tolkien viewed sub-creation not merely as just another tool in the writer’s tool belt (along with plotting and characterization, say) but rather as a stand-alone activity that had merit in and of itself. This belief is what allowed Tolkien to be such a profligate world builder. He created vastly more material than ever made it into his books. He called this trove of linguistics, geography, history, myth, culture and genealogy the Legendarium, defined by the Tokien Gateway as “the entirety of J.R.R. Tolkien’s works concerning his imagined world of Arda.”

The relationship between The Legendarium and his literary works (like The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings) an important one in two ways. First, as noted, the Legendarium is far larger. According to Downing, for example, “Quenya, the elvish tongue… had a vocabulary of several hundred words, with consistent declensions and etymologies” by the time he completed The Lord of The Rings, but only a sparse handful of those words appear in the text. The second is that they are, to a large degree, independent. The Legendarium was not completed for the purpose of writing The Lord of the Rings but as an independent exercise undertaken for its own merits. The stories came later, not as an afterthought, but as a distinct labor with their own objectives and process.

Of course in practice the two activities—the world-building and the story-telling—were intertwined. The point is simply that there were two activities, and Tolkien loved them both.

His reckless and extravagant acts of creation are what, to a large extent, made his fiction seems to vibrant and real. Early in The Lord of the Rings, Frodo is nearly killed by a barrow-wight. If you consult Appendix A you will learn that he had been trapped in the cairn of the last prince of Cardolan. Who was that prince? What was Cardolan? I have no idea, but I also have no doubt that Tolkien’s Legendarium contains the answers to both questions. This is just one example of many—to many to count!—where the characters in The Lord of the Rings came across an abandoned place that was steeped in history and drama not directly related to the story.

Argonath is, among these many examples, the one that has haunted me for the longest. Here’s the passage, which comes from the chapter “The Great River” near the very end of The Two Towers, that has haunted me since I first read it in a pop-up camper in Tennessee on a summer vacation when I was only 11 or 12 years old:

Upon great pedestals founded in the deep waters stood two great kings of stone: still with blurred eyes and crannied brows they frowned upon the North. The left hand of each was raised palm outwards in gesture of warning; in each right hand there was an axe; upon each head there was a crumbling helm and crown. Great power and majesty they still wore, the silent wardens of a long-vanished kingdom.

What impressed me then and has remained with me ever since is that Arganoth has basically nothing to do with the rest of the story. Sure, it marks the historic northern boundary of Gondor, but by the time we get to The Lord of the Rings, Gondor has already shrunk far from those boundaries. And sure, Strider / Aragorn is a descendent of the antecedents of Gondor, but does that really matter for the story? No, it doesn’t, and that’s why it makes Middle Earth beautiful. It is creation for creation’s sake. I knew, even as a kid, that Tolkien understood perfectly who had built these strange, forgotten pillars and why and the knowledge that he knew things that weren’t in the book is what made the book seem so real. Just like the real world: there’s always more history in Tolkien’s work than you can take in at once. [ref]My confidence was not misplaced, as it turns out. “It was originally constructed about TA 1340 at the order of Rómendacil II to mark the northern border of Gondor,” according to The Lord of the Rings Wiki.[/ref]

So Tolkien loved sub-creation for its own sake, which caused him to do quite a lot of it, which in turn made the setting of The Lord of the Rings vivid beyond compare, which in turn led to the widespread popular love of those books, which in turn helped found the genre of high fantasy. Now, over a half century later, high fantasy is a genre cluttered with books full of maps of fantasy countries and continents, but none of them have remotely captured the grandeur of Tolkien’s original because they have tried to imitate his product without understanding the process that led to it. And Brandon Sanderson’s Words of Radiance (despite being a very fine book) is the perfect example of how it has all gone sideways since Tolkien.

High fantasy writers since Tolkien have created less and showed off more. The bigger problem is not that they have created less in total but rather that the ratio of what they have created for the setting to what they show you on the pages of their novels has diminished substantially. Sanderson’s Stormlight Archives are a great example of this problem because I get the feeling that he very well might, by the time he’s done, eclipse Tolkien in terms of sheer creative output, but he also seems bound and determined to shoehorn every last thought he has ever had about his creations directly into the text. [ref]I’m sure he’s leaving lots out by his own estimation, but compared to Tolkien there’s pretty much nothing left to the imagination at all.[/ref] This has three bad consequences.

First: it makes the stories bloated. Sanderson seems preoccupied with making sure you know exactly how the magical system he has created works. How does that help the story? Did Tolkien need to tell us how Gandalf’s magic worked in excruciating detail? And even if you argue that Sanderson’s strong suit is magical systems where Tolkien’s was language, the metaphor still holds: no one reads The Lord of the Rings and feels like someone tried to sneak a lecture on linguistics into their fantasy novel. The linguistics are there, of course, but Tolkien doesn’t feel the need to beat you over the head with them, whereas large portions of Words of Radiance revolve around nothing other than frog-marching the reader through a tour of Sanderson’s fabricated lore. [ref]Come hell or high water, anyone who finishes the novel will understand the difference between an Honorblade and a Shardblade.[/ref]

Second: it makes the worlds seem flimsy. Far from having an abundance of lost cities and forgotten heroes to populate the fringes of the story, Words of Radiance is rife with extra characters and stories (in the Interludes sections especially) that over-explain the universe. You rapidly get the impression that nothing—no religion, concept, magical power, artifact, civilization, or anything else—is going to be introduced in this book without being explained to death. Reading The Lord of the Rings feels like visiting another world because you know that there is a story underneath every stone, far more than you will actually experience in the text. Reading Words of Radiance feels like visiting a theme park ride by comparison: you have the impression that if you take even one step off the beaten path you’d see the 2×4’s holding up the painted backdrops. No matter how much you create, you have to hold something back or the reader is going to see through your creation.[ref]You can always publish it later in The Silmarillion if you need to.[/ref]

Third: it requires a very specific scope. Because high fantasy authors feel the need to cram every part of their sub-creation into the stories they write and because they often invent their worlds from the very moment of first creation, they trap themselves into writing only cosmic stories. This is bad because Big Questions are easy to raise but hard to answer, and so right off the bat high fantasy writers are painting themselves into a difficult corner. But even if they can pull it off, the fact remains that they are only capable of writing mega-epics. Which, to be clear, is a category that excludes the founding high fantasy story: The Lord of the Rings. Did you notice that the definition of Legendarium included the “world of Arda.” What, exactly, is that? You wouldn’t know, based on reading The Lord of the Rings, just as you would never have heard of Eru Ilúvatar (“the supreme God of Elves and Men” and “the single omnipotent creator”) nor of the Ainur (“divine spirits, the ‘Holy Ones’” who actually shaped Middle Earth).

Tolkien did all the work of sub-creation back to the Big Bang of Middle Earth, and you can read all about it in The Silmarillion, but none of truly foundational lore shows up in The Lord of the Rings at all. It’s true that Sauron is a pretty epic bad guy, but the scope of the The Lord of the Rings is actually quite limited. It’s the story of one particular time that one particular bad guy threatened the peace of one particular region of the world. Gandalf is clear that this isn’t some ultimate final battle or anything like it. He calls the last military campaign “The great battle of our time.” (emphasis added) and when Frodo says “I wish the ring had never come to me. I wish none of this had happened,” Gandalf replies: “So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us” (emphasis added). Eru never shows up. Neither do the Ainur. The story of The Lord of the Rings is, compared to the majestic backstory Tolkien had available, mundane. It is almost an anti-epic. It’s emphatically not a story that tries to be about everything all at once and it’s in that specificity that it becomes singular and glorious. I generally dislike high fantasy as a genre precisely because it has lost sight of imperative of specificity that underlies the very definition of narrative.

It’s worth noting at this point an important fact: Tolkien originally tried to include The Silmarillion for publication in the same book as The Lord of the Rings.[ref]According to Wikipedia, but with citations.[/ref] It wasn’t his foresight that saw The Lord of the Rings published as a standalone text, but rather the imposition of editors and publishers who viewed the former work as uninteresting to the public. And they were right: The Silmarillion (which I have read and very much enjoyed) is only good because The Lord of the Rings is great.

The point of this essay is therefore not that Tolkien was an omniscient genius who is the only one to do high fantasy the right way, but simply that his theory of sub-creation is deeply important to the success—both artistically and commercially—of The Lord of the Rings and that anyone who wants to emulate that aspect of his success should study it, understand it, and emulate it.

Tolkien believed in sub-creation as an independently worthy action and engaged in it as a form of worship, and that explains the creation of the vast Legendarium. This was the well from which he dipped to draw out works like The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and it makes sense to think of them as two separate kinds of projects: the world-building vs. the narrative itself.

Subsequent high fantasy authors have failed to fully appreciate this distinction and especially the worthwhile endeavor of sub-creation for its own sake. This is understandable. Writers get in the business to tell stories, not to write thousands of pages of backstory and setting that no one will ever see. They see world-building as necessary to telling fantasy stories, and they see Tolkien praised for the central place his world-building played in The Lord of the Rings, but they end up emulating the final product without fully understanding the process that went into it. They build the world for the story instead of for itself.

What’s more, the process is daunting. It requires an extraordinary amount of work that, in a way, seems wasteful. Why create an entire language—grammar, vocabulary, etymology and all—when just a few fun-sounding syllables here and there will do? The temptation to short-change the world-building and to only build what you need is overwhelming for authors who are not generally flush with cash and are often working on deadlines. How is it possible to justify the kind of exorbitant labor of love that Tolkien has engaged in?

For most people, it isn’t possible, and that is one major reason why The Lord of the Rings still stands alone. No one else seems able or willing to do what Tolkien did. They keep trying to get similar results, however, and I guess that’s good enough for fantasy’s audience.

If all of this sounds a little bit too harsh, let me restate what I said at the outset: even if I hold the genre of high fantasy in low regard as a whole I love The Lord of the Rings and I also like the Stormlight Archives quite a lot. I expect to read all of them.

But I stand by my criticism. It’s not that Sanderson hasn’t invested enough in world-building (he probably has), but it’s more that he just doesn’t seem willing to view that world-building as both intrinsically valuable and distinct from the narrative. He seems to want to cram all of it into the books. And that’s a bad thing. The Stormlight Archives are still excellent, in my opinion, but they are not nearly as good as they could be if they were treated as truly independent stories rather than vehicles for delivering world-building content. An abridged treatment would really, in this case, be a better story. Sanderson could have more focus without Interludes so tangential they make you want to pull your hair out [ref]I read them all, but my brother just started skipping them[/ref], a richer and more immersive world, and greater freedom in the scope he chose to pick. Sanderson is a great writer, but there is still only one J. R. R. Tolkien.

I don’t disagree with you’re overall argument, Nathaniel, but I would point out that as it specifically applies to Sanderson, you’re dealing with the wrong scale — Sanderson’s canvas is the Cosmere, the universe, and not just the world on which the Stormlight Archives take place. That doesn’t change the fact that he is cramming too much into the Stormlight Archives (although even with the interludes, I think there’s still a lot left unsaid). But I do think his overall project and output is closer to Tolkien’s than you portray in this post. And if you take all of his work in the Cosmere as a whole, a lot more gaps and unexplained histories/systems/characters exist. I agree with you, though, that he should ratchet things back just a bit (not so much with the interludes but with the details of the magic systems), but he’s a post-Wheel of Time, post-D&D author so his tendency is going to be to cram things in.

Did you ever read David Eddings’ Belgariad and Mallorean series? They were the first fantasy I ever read, so they still hold a place in my heart and I still love their protagonist more than any other. At some point he published his “homework” as The Rivan Codex (which, in the two stories mentioned above, is actually the name of some ancient document). Similarly to the Silmarillion, it’s pretty dry but the introduction (if I remember correctly) has a similar thesis: authors gotta do their homework.

One author who does what you like, to an even more extreme version than Tolkein, is Gene Wolfe. In any of his works, it’s clear there’s so much more going on than the narrative tells you – though Wolfe always has an unreliable narrator, so it’s even harder to tell exactly what is “off screen* (or *off page*, I guess). Gene Wolfe’s “The Book of the New Sun” is sword and sorcery, high fantasy, and hard science fiction all at the same, but it fits your ideal.

And Gene Wolfe is Roman Catholic too.

You made me look so now you get to find out. When the kingdom of Numenor assailed the Undying Lands due to the lies of Sauron (a Maia) the land of Numenor was swallowed (like Atlantis) with only 9 ships escaping. Those who escaped were apparently called ”the Faithful’ and upon reaching the shores of Middle Earth established the realms of Arnor and Gondor.

Dealing specifically in this case with the realm of Arnor or the Northern Kingdom, from Elendil to Earendur there were 8 high kings. The sons of Earendur didn’t get along and so split the kingdom into three: Arthedain, Rhudaur, and Cardolan. These men were known as Dunedain or ‘men of the west’.

Cardolan was in the south, Brandywine to Greyflood rivers, and the Great Road (?maybe the Great East road?). This area includes the South Downs perhaps which would be a likely location for the situation you mentioned with Frodo.

Arthedain was the northwest, between Brandywine and Lune rivers, and north of the Great Road (?) to the Weather Hills. This area includes the Shire.

Rhudaur was north east, between Ettenmoors, weather Hills, and Misty Mountains and appears to be much smaller than the other two. As noted, the last prince of Cardolan did perish, as well as eventually the line holding Rhudaur. The dispute was often between Cardolan and Rhudaur over the Weather Hills as the Tower of Amon Sul (Weather Top) was there holding the Palantir of the north, and the kingdom of Arthedain held the other two Palantir.

Arthedain was ruled by the eldest son of Earendur whos names was Amlaith of Fornost (southern tip of the North Downs). The last king of Arthedain was Arvedui who’s son was noted as a Cheiftain named Aranarth, from which Aragorn II comes (aka Elessar Telcontar) who became King of Gondor at the end of the trilogy.

Wm-

I left out discussion of the Cosmere because it doesn’t make any appearance from the text of the Stormlight Archives.

I really like the idea of Sanderson working on a grand meta-verse that spans multiple, apparently independent narratives. It’s very cool and could be ground-breaking. But I still think the criticisms apply: the individual works are bloated and there doesn’t seem to be any hint of a grander vision in the books so far.

It could happen, though, and I hope it does. (I also hope he starts writing more focused books, however. The excess baggage really takes the edge off of what could be some very, very sharp storytelling.)

Trevor-

I read the Belgariad series a long, long time ago when I was probably 12-14. I liked it at the time, but it was my last foray into high fantasy (until Sanderson). My overall impression wasn’t really favorable (there’s a reason it was the last), but it’s been a long time and I can’t even remember why I didn’t like them. (And I did like them enough to finish the one series, as I recall, but that was about the time I definitively switched from fantasy to sci-fi.)

Ivan-

I’ve been hearing lots about Gene Wolf as (if I recall correctly) one of the literary school of sci-fi writers. So I’ve definitely been meaning to give his work a read, but I haven’t gotten to it yet. But you’ve moved him closer to the top of my mental “to read” list!

Joel-

See? It’s all there. It’s always all there with Tolkien.

In some ways, George R. R. Martin is like the anti-Tolkien. Tolkien had really grim, ambiguous history (e.g. in The Silmarillion) but he presented a mythological, heroic version of it in The Lord of the Rings.

Martin skips the heroic gloss and just makes the grim, ambiguous history the point. In a way, Martin is just a guy who decided to write backstory in a compelling way and–to be honest–I’m not entirely sure how he does it. I’ve read Game of Thrones and also an extended prequel novella that was part of an anthology and his writing is mesmerizing despite the fact that it really reads more like a historical overview than a “story” in the conventional sense of the word.

“I left out discussion of the Cosmere because it doesn’t make any appearance from the text of the Stormlight Archives.”

The Sanderson-heads would disagree (although I must admit that I’m not enough of one to know all the details), but it’s much more subtle and easter-egg-ish than it is in Tolkien. And that’s an intentional, commercial decision that Sanderson has made. My tastes run more to yours, but I understand why he has made that decision. And I don’t think it’s solely commercial considerations — it’s simply follows from the type of reader he is and what he’s reacting to in the field. And while it’s still early to tell, I think that the interludes (which are actually a series of short stories and novelettes) are preferable to the massive bloat you get with A Song of Ice and Fire and the multiplication of point of view characters. In my reading experience, the bloat and over-explaining is more with the main story lines than the interludes.

The genius of Martin is that he sets things up as a standard heroic fantasy story and then demolishes that hope while at the same time sort of preserving it in places. I really hope that he can pull it off in the end, but at this point, I have no idea what a satisfying ending would look like.

Side note, the wizards (Saruman, Radagast, Gandalf) as well as Sauron are all called Maiar which from what I’ve gleaned through the years would equate almost to ‘Angel’ if the Ainur were considered the gods of Middle Earth. Of note there are two more called Ithryn Luin or Blue Wizards of whom there is little said. IIRC they traveled east and that was that.

The Balrog which Gandalf fought was also a Maiar which had been corrupted by Morgoth (the rebelious Ainur whose prodigy was Sauron). Gandalf was apparently able to end the Balrog but in the attempt also lost his physical form and returned to the Ainur, who then sent him back as his task was not yet accomplished.

I am certain, though I have no proof at this time that the color of the robes was linked directly to the power of the wizard. Thus as Gandalf the Grey he was not able to overcome Saruman the White but as Gandalf the White he was able to overcome Saruman, especially since Saruman had been corrupted by Sauron and was likely losing power because of it. Sauron was likely taking as much power from Saruman as he could in an attempt to once again take physical form. This would apparently give him an immense amount of power and likely would have changed the narrative ending to LOTR entirely.

Obviously much of the last part is conjecture on my part.

I don’t think Martin is looking for a ‘satisfying ending’. I gave up on that hope before the 5th book ended, though I was truly and sadly surprised by one death in the 5th book….which I suppose is what broke my hope entirely for the ending. My bet is that he writes an entirely frustrating ending that leaves you screaming something along the lines of ‘WTF’…..

Yes I will be finishing whatever he writes, despite (or perhaps because of) my hope being totally broken.

Ah, but that would likely be a satisfying ending for me. As opposed to the Dark Tower series where King tries to have it both ways and then some.

I’m more worried about no ending or an ending that tries so hard to avoid intersecting with the body of fan theory that has emerged to fill the void of no books that it feels completely discontinuous.

“I left out discussion of the Cosmere because it doesn’t make any appearance from the text of the Stormlight Archives”

The Stormlight Archives are big tomes, so it’s possible you missed the handful of times the word “cosmere” actually appeared in the two volumes, plus the character of Hoid/the Wit features rather prominently in both volumes of the SA, and he appears in all of Brandon’s cosmere tales).

He’s not related to me (as far as I can tell), but I get a little touchy about people leaving the “e” off the end of Wolfe (since that’s my last name too),

As I mentioned above, Brandon actually uses the word “cosmere” in a handful of spots in the SA, and the use of Hoid in all his books isn’t really subtle, especially since Hoid, in the second volume of the SA, talks fairly directly about the metastory linking all the cosmere books.

Heck, Sanderson even has Hoid bring in a sword from Warbreaker in at the end of the second volume, and that book takes place on a differentworld. However, Brandon doesn’t state where the sword comes from – you only know that if you’ve read Warbreaker. It’s left as one of those “mysteries” Nathaniel seems to like.

Yep. There’s more too. It’s quite the rabbit hole.

Also, I suggest starting with “The Book of the New Sun” (which was originally published as four volumes, then two, and then one, so you can find it in various varied editions, plus the standalone 5th book “The Urth of the New Sun”), since that’s his best known work.

After that, there’s anywhere you could go. “The Best of Gene Wolfe” short story collection is a good overview of his shorter work. “The Fifth Head of Cerebus” is also fairly well known, but more opaque (Wolfe loves his unreliable narrators).

He comes across as a post-modernist to a lot of people because his works are often opaque (but worth the mental effort), but he’s actually very much a literary modernist.

I don’t think that’s really the kind of mystery I like. Having not read Warbreaker, I have no idea that a mystery exists at all. That’s the opposite of what I have in mind. Tolkien left clues and hints of other lore that (1) wasn’t related to his story and (2) was prominent for any one to see.

What you’re saying is that Sanderson leaves clues that (1) are directly related to his plot and (2) are totally invisible unless you know what to look for.

Tolkien’s mysteries were inclusive: they were for anyone. And they were spurious, which made them seem reach. They didn’t relate in any meaningful way to the plot. They were just there fore the sheer hell of it, and that made the world seem richer because the real world contains lots of things that are just there, and that don’t fit a story.

Sanderson’s mysteries are exclusive: they are there for his diehard fans. And they are part of his grand narrative. So they aren’t beautiful ornamentation. They are just more strory which I think we’ve already all agreed he has too much of as it is.

The more I hear about these things, the less I think of Sanderson as a writer. This kind of genre insularity is easy to miss if you’re on the inside (that happens with me and sci-fi), but it’s poison in the long run.

Well, I know it’s a big book, but I’m wondering how closely you actually read it, based on this comment.

The uses of cosmere were done in passing, so I can see not quite noticing those, but when the sword from Warbreaker shows up, it’s pretty clearly labeled a mystery that has no clear explanation. The character it’s given to remarks that it doesn’t quite fit in or make sense, that there’s something mysterious about it. Knowing where it comes from is a bonus for diehard fans, but for the non-diehards it’s just a mystery that will likely never be resolved in the SA series proper.

As for saying all of this is “poisonous” – those are strong words for basically saying “it’s not what I want to read” somehow equaling “this is not how it should be.”

I think that kind of deep continuity is only poisonous if it takes over the works. In order to maintain the core audience, works of fantasy often have to have those kinds of references. However, the core audience isn’t usually enough. They have to walk to a line between keeping the core audience and appealing to newbies. (it’s like how superhero comics, if they abandon continuity, lose the core audience – but when they pander to the core audience, they don’t get the casual readers that are needed to keep the title afloat).

Brandon, methinks, walks that line very well. There’s plenty of deep continuity to keep the superfans happy, but the works are accessible enough for casual readers (despite their length – hence their bestselling status). If it were to take over and you would have to be a superfan to understand what was going on, then it becomes poisonous.

However, you seem to be arguing authors should never, ever have deep continuity references, and that (to me) seems just as wrongheaded as going overboard in that area.

Ivan-

There’s a specific kind of dangling thread that improves world building, and the Argonath is an example. It serves minimal plot purpose (it’s an element in Strider’s transition to Aragorn, but overkill for that task), but it does convey that “Hey, this is a lived in world.”

What you’ve referenced with Sanderson are (1) Easter eggs no one can find if they don’t know to look for them and (2) random stuff that is just random unless you’re in on a secret.

Neither one does one of the core jobs that world-building should do, which is to convey that there is more to the world in which the story takes place than just it’s role as the setting for that particular story.

That’s not what I’m saying. What I’m saying is that when you have authors who are writing in a way that is only accessible to devotee of a sub-genre, you’re effectively poisoning that genre by making it inaccessible to newcomers.

This is something I understand pretty well because–after years and years of reading sci-fi–I started to develop a taste for some really inaccessible stuff. And it was only when I had other authors write about accessibility and/or tried to share the books with others that I realized just how deep down the rabbit hole I was.

So it’s not “I don’t like it so I will call it something mean.” It’s really an assessment that insular writing will be bad for a genre in the long run, as I think it has been bad for sci fi.

“It’s really an assessment that insular writing will be bad for a genre in the long run, as I think it has been bad for sci fi.”

I’m not sure how to square “insular writing” with “mega bestseller status.”

Really, you somewhat dodged my entire main point about how the core audience demands these kinds of “easter eggs” and how I feel Brandon manages to walk the line between making his work accessible while still including enough “stuff” for the devoted superfans. Your argument seems to be Brandon should only aim for accessibility, period – but that’s a clear way to lose a core audience, and while the core is never enough by itself, without them, the whole thing can fall apart.

But then, you did state at the beginning you don’t like high fantasy as a genre, so on some level this seems like arguing that you don’t like football, but you did like one game that was played back in the 1930s, so modern football would be best if it was run like the old time days.

I do think you would like Gene Wolfe. He’s my favorite author (Brandon is in the top 10, but near the bottom of my top ten), and he is very literary, and he very much fits the mold of what you seem to like in high fantasy.

Speaking of extraneous details, I’m not sure that Tolkien was really innocent of this. As much as I appreciate his work as an author and founder of a genre that I love, I truly struggled to get through LOTR.

The amount of words he devoted to the introduction of goblins, elves, and other creatures always seemed like overkill to me. Detailed, but too long.

Sanderson definitely enjoys explaining his magic systems. But I think where I was truly dissatisfied is his tendency to shy away from killing off characters. I thought there were two characters in Words of Radiance that should have died near the end of the book.

The Death of High Fantasy is a pretty dramatic title. I don’t think high fantasy is dying – but if it is, it’s not from lack of world building. I think it’s because “gritty fantasy” has become all the rage. For some reason, people like heroes who are not just flawed, but downright tainted. That’s one that I don’t really understand.

I like heroes.

In that case I’d say a ‘no ending’ setup as much as I’d hate that.

I have to agree that Tolkien, as several other authors have also done, would occasionally spend inordinate amounts of time detailing something not plot centric or even useful for moving the story forward. The good news on that is it allows a vivid picture of what he is talking about, but it is excruciating to get through at times.

I don’t think he did it on purpose though, he wasn’t a sadist. Just that he had so much that he wanted to give to the world he created. It was a passion and a love. I mean, just go look at how many languages he knew, including the ones he created.

Sanderson is accessible. They were designed as such. Cosmere knowledge isn’t important to the reading of any individual series. Anyone could pick up Mistborn or Stormlight Archive without any prior knowledge and it wouldn’t lessen the experience. Cosmere probably shouldn’t have even been brought up here in the first place.

I don’t see what you’re saying at all about Tolkien being inclusive and Sanderson somehow being exclusive. Yes, there are some mysteries only die hard fans will get, but they are only bonus. There are still plenty of mysteries going around. People who just pick up the books and read them become the die hard fans oftentimes before knowing about the behind the scenes stuff. Ultimately people like them because their great books with great characters and story.

Anyway, I don’t think it has too much story. That’s one of the many things I like about it. The problems you mention aren’t actually probl It’s more story focused. It’s a different style than Tolkien, but it’s not an inferior style. Obviously Sanderson is a really intelligent author and makes these choices deliberately. Obviously you like the more Tolkien mysticism style, but that doesn’t mean the Sanderson style with scientific magic, story based mysteries, and nothing thrown in just for the heck of it is inferior. You can see it’s a lived in world by all the ways of life shown through characters in different parts of the world. But, I’m there for the story, and things that don’t serve a purpose would distract from that.

It doesn’t mean I think less of Tolkien, I just prefer Sanderson’s style and his books are more accessible to me (even before knowing about the hidden backstory).