First, let me say that I promise not to make a habit out of cherry picking MotherJones articles to use as a punching bag.[ref]I’m referring to this post I wrote last week, btw.[/ref] I realize it’s unhealthy to spend too much time recapitulating the perceived failures of one’s ideological opponents, but I’m violating my own rule for two reasons. First, I am more inclined to use any article as a rhetorical punching bag when I feel it is, itself, perpetuating partisanship in a particularly noxious way. Second, I think some of the issues raised in this post will be genuinely interesting and important.

So this is what I saw on MotherJones last week:

I took a screen grab because it’s not just the article that I found so captivating. It’s the juxtaposition of an article about “how the superrich spoil it for the rest of us” with an advertisement for Patek Philippe watches. I’m no watch connoisseur, but that looks pretty expensive to me. Google would seem to agree:

The cheapest watch on that list costs about what both of my family’s cars cost put together. And the most expensive literally costs more than our house did, back before the housing bubble burst when we owned our own home. So I have to wonder: what kind of person is concerned about “the superrich” and in the market for a watch that costs tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars? Well, apparently some of the folks who read MotherJones fit that particular bill.[ref]Of course it’s possible that the ad was served to me by some process that has nothing to do with MotherJones as a magazine. If so: (1) they need to fix their algorithm (2) the rest of this article will still be interesting.[/ref]

So what makes the post more than a mere gotcha? Well, I have two serious thoughts to add that I hope elevate us beyond mere rabblerousery[ref]I, for one, think “rabblerousery” should be a word.[/ref]

The first is a quick note on inflation-adjusted dollars. One of the charts claims that if median US wages had kept pace with the economy since 1970, then they would currently be at $92,000 instead of $50,000. Mathematically, I am sure that is probably correct. But can you really compare 1970s dollars to 2010s dollars so easily? Let me ask you this: would you rather have $92,000 in 1970 or $50,000 in 2014? How about $92,000 in 1714 vs. $50,000 in 2114?

Money, it turns out, isn’t everything even when you’re talking about economics.Think about some of the things you would lose by going back to the 1970’s: the Internet, cell phones, and Game of Thrones all come to mind. But it’s not just fun and games, would you trade 1970s medicine for 2014 medicine? Would you, if you had cancer? If your child did?

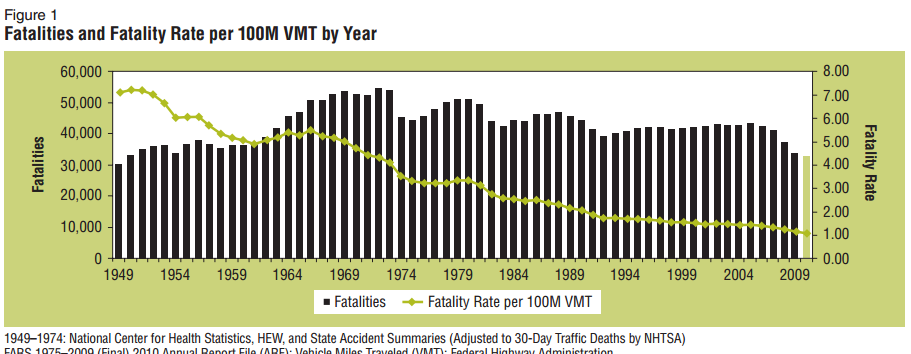

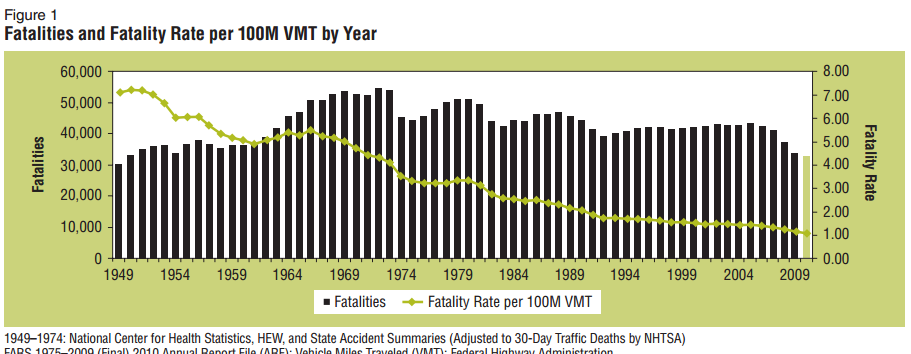

So that’s a chart that[ref]From the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration[/ref] shows your likelihood of dying in a car crash per 100,000,000 vehicle miles traveled (VMT). You can see in the 1970s it was about 3 to 4. By 2009 it was about 1. So your chances of dying in a car crash (per mile traveled) were roughly triple or quadruple in the 1970s what they are today. This is just one off-the-top-of-my-head example of the kind of comparison that inflation-adjusted wages don’t capture.[ref]It doesn’t escape my notice that a large part of the reason for increasing safety is government regulation, which is (broadly considered) a left-leaning policy. If that admission softens the tone of this piece: good.[/ref]

My point is just that there actually isn’t a way to compare our lives in the 1970s with the 2000s in a way that allows any kind of meaningful analysis. Inflation is calculated by economists who first create a bundle of goods (gasoline, food, clothes, etc.) that is supposed to be more or less representative of what a person or household buys, and then track the change in price of that bundle of goods over time. That’s the best they can reasonably do, and for a fairly consistent commodity (like wheat) it does OK. But it fails to address increases in product quality (e.g. a laptop in 2014 is not the same animal as a laptop in 2004), not to mention new products (e.g. a laptop in 2014 vs… ? in 1974), not to mention increases in public goods (like better air quality, perhaps) that are not captured by any bundle of goods that a person purchases. In short: saying that median income has stagnated doesn’t actually tell you if people are better or worse off, or at least, not nearly as clearly as MotherJones might want you to think.

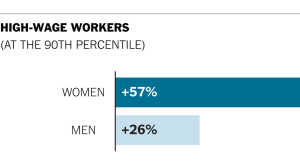

The second thing to consider, and this one will not be very popular, is the question of why the median wages haven’t risen much over the last 40 years. MotherJones specifies that it’s “the superrich,” but that’s not a theory it’s a slogan. It’s designed to make people feel better, not to explain things. Here, on the other hand, is a theory that might actually offer some plausible explanation: the increasing numbers of women in the workplace suppress wages.[ref]Hey, I told you it wasn’t going to be popular. That doesn’t mean it’s not true.[/ref] This is econ 101: when supply (the number of workers, in this case) goes up then prices (the wages a worker earns, in this case) go down. The HuffPo conveniently has some numbers pegged to 1970 for comparison:

In terms of sheer numbers, women’s presence in the labor force has increased dramatically, from 30.3 million in 1970 to 72.7 million during 2006-2010. Convert that to percentages and we find that women made up 37.97 percent of the labor force in 1970 compared to 47.21 percent between 2006 and 2010.

At least some [ref]How much? I won’t try to guess or research that question for this piece.[/ref] of the wage stagnation therefore comes from women entering the work place. That’s not the only effect, by the way. At least one economic paper (based on dramatic changes in female participation in the workplace around World War II) found that not only did wages go down when women entered the workplace, but that wage inequality increased between high and low incomes and even that the gender pay gap increased. This might sound like ultra-right-wing propagandizing, but none less than Elizabeth Warren has contributed significantly to the understanding that women entering the work force has had negative impacts on our economy. In The Two Income Trap, Warren basically argued that (1) dual-income families are less financially secure than single-income families because if there is no insurance policy[ref]Meaning: that if worker loses his or her job in a single-income family, the other spouse can go to work to make up at least some of the difference, but in a 2-income family there is no Plan B.[/ref] and (2) dual-income families have bid up the cost of living (especially homes) to a point where single-income families can’t really compete anymore, which creates a vicious cycle. MotherJones covered this back in 2004, by the way, and they asked the book’s coauthor Amelia Tyagi about the apparently right-wing narrative she seemed to endorse:

MJ.com: Some conservative commentators might see this as evidence that the mother should return home.

AT: [Laughs] Right. Of course, the notion that mothers are all going to run pell-mell back to the hearth and turn back the clock to 1950 is absurd. But that aside, a big part of the two-income trap is that families have basically bid up the cost of living. Housing is a big example. A generation ago, an average family could buy an average home on one income. Today you can’t do that in three-quarters of American cities. We all know that housing prices are going up, but what most people don’t realize is that this has become a family problem. Housing prices are rising twice as fast for families with kids.

It’s telling that Tyagi replies to MotherJones’ comment with laughter and then sets the question aside. That’s because the evidence is actually pretty clear: two-income families have significant costs for our society. And let me be equally clear: my point is not that we should send all women back home. As far as the evidence presented so far is concerned, an equally prudent strategy (from a socio-economic standpoint) would have been to stick with single-income family structure, but to have men become the primary caregiver in 1/2 of the families, just as one possible example.

My point isn’t that the left-wing view is wrong and the right-wing view is right. My point is that reality doesn’t care about your politics. Or mine. If we really want to do our level best to fix problems, that means we’ve got to be more willing to entertain explanations and solutions that depart from everybody’s narrative and agenda. Who benefits politically from the fact that two-income families are bad for the country? I’m not sure anybody does, but if it’s true (and it seems to be true) then it’s important to know so. Maybe it will help us invent some new policy that will make things better, but at least it will help us avoid snake oil policies that will do no good.

Something else I like about this line of argument–and this does appeal to the conservative within me–is that it underscores the tragic vision conservatives have for our world. Want to improve society by making the work place more egalitarian on gender grounds? OK, but there are going to be costs. And some of those costs will be: stagnant wages, an increased gender pay gap, and increased income inequality.

Or, you know, you could ignore research that is politically uncomfortable and just blame the superrich. While you try to sell them luxury watches.

Look, my big problem with MotherJones has nothing to do with the fact that it is liberal. I will admit that doesn’t endear them to me, but there are lots of liberals I admire and respect (some of whom comment here.) If you want to see what really gets to me about MotherJones, just glance back at the very first line of the article. Or, to save you time, I’ll quote it here:

Want more rage?

No, MJ. I don’t think that’s what America needs right now. But thanks for being open and honest about what–even more than luxury watches–it is that you’ve got on offer.