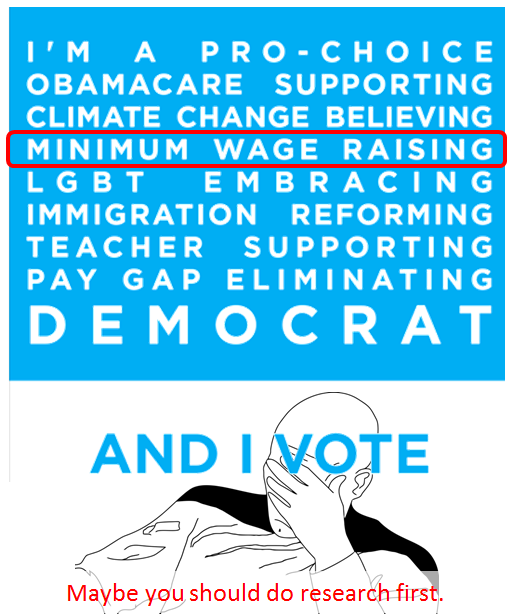

I saw the image above on a friend’s Facebook profile on Tuesday. Well, not exactly. You can probably tell what parts I added to it. Don’t get me wrong, minimum wage isn’t the only thing I take issue with on that list, but it’s just the one that is just objectively dumb. We’ve written about exactly why the minimum wage is foolish here at DR many times already, but life handed me a fresh example, so here goes. The WSJ reports that (1) McDonald’s profits were down 30% in Q3 2014 and that (2):

By the third quarter of next year, McDonald’s plans to introduce new technology in some markets “to make it easier for customers to order and pay for food digitally and to give people the ability to customize their orders,” reports the Journal.

In other words: the Golden Arches are losing money and plan to economize by replacing workers with machines. Is it any coincidence that this announcement comes just after CEO Don Thompson signed endorsed President Obama’s call to raise the minimum wage? No, it isn’t. It’s politics. Ignorant people call for hiking the minimum wage without realizing that they’re going to cannibalize jobs. Astute CEO gives up on trying to be reasonable and just goes with the flow, knowing full well that if/when the minimum wage rises, his company will be able to survive through automation.

There are much, much better policies to fight poverty. Why is no one rallying around making the efficient and effective Earned Income Tax Credit even more powerful? Politics. Calling for minimum wage hikes is like having the village pressure the one doctor into bleeding the patient to save his life. “But this won’t make the patient better,” the doctor cries. “What,” says the rabble rouser, “Are you saying you want the patient to die! Apply the leeches!” It’s a great way to make the doctor look heartless. It’s not a good way to help the patient get better.

So, how low would the minimum wage have to be to prevent companies like McDonalds from automating jobs out of existence? There may be a number you could point to today, but it would be short-lived. The problem is that Wall Street demands perpetually INCREASING PROFITS. Consistent profits are not good enough. That is unsustainable. Eventually and inevitably, this leads to crashes.

We are heading into a labor crisis. The market demands productivity increases and profit increases – that is in direct conflict to job creation and job satisfaction. More and more people are being put out of work by automation. This trend is just getting started, and is going to be felt across many industries that have not had to deal with this yet.

The question for us, as a nation of families and individuals, is what do we value? Do we value corporations’ contributions of cheap stuff, or do we value people’s labor and opportunity? If you think the best thing this country can have is cheap goods, then eliminating the minimum wage is exactly the right move. If, on the other hand, you think there is value to allowing people to work, and be able to support a family on a single income, then the minimum wage needs to be raised. It is not a long term solution, though, and is becoming less and less effective. But it does fill an immediate need.

Nuanced political discussion is often best served by analyzing our assumptions and the problem that particular measures attempt to address, rather than just looking at specific measures.

What information about the minimum wage do you have that The Economist lacks, making your position so certain while many other smart economists have nuanced views?

Ryan-

There are several things to keep in mind.

First, I’m specifically talking about a tradeoff of EITC vs. minimum wage. That policy comparison is different from asking about the minimum wage in isolation as an academic exercise.

As for the empirical question, there’s little evidence that minimum wage increases have hurt jobs in the past. This is because minimum wage hikes have tended to be temporary. This changes the incentives of corporations who are responding to them, because investing in automation right now would compound the hit to their bottom line in exchange for a reduced impact in the future where (thanks to inflation) the real impact of the minimum wage would be declining. But recent proposals (like President Obama’s) were based on raising the minimum wage and chaining it to inflation. That’s a much more dangerous proposition. Additionally, there’s been some very smart and very recent evidence that looks at how corporations tend to gradually phase in automation in response to increased minimum wage rather than investing in big lump sums.

In short: I recognize that there can be lots of nuance about the issue, but based both on new research and on practical policy comparison with an alternative poverty-fighting measure I just really don’t think there’s much room for debate.

I’d be curious to see a policy question posed to economists that specifically asked about the minimum wage vs. the EITC, however. I think you’d get very different responses than a minimum wage question alone.

Ryan-

You could check this out as an example: http://www.economist.com/node/8090466

Specifically the last paragraph (with some emphasis added):

Tyler-

I think we have very different historical and economic perspectives on this issue. For example, you write that: “More and more people are being put out of work by automation. This trend is just getting started…”

From my perspective, this trend has been going on in a big way for over two hundred years. The Luddites were doing their thing (smashing power looms and other automated equipment) in the 1811-1817 range. In what ways are your concerns materially different from theirs? And, to go along with that, would you prefer a world in which the Luddites won out and we froze technology at the early steam age?

There’s no practical way to stop McDonald’s from automating, and–in the long run–there’s absolutely no reason that we would want them to do so. Automation is good. It’s also very, very old news.

This isn’t to say that there are no concerns. But the problems we face have to do (1) with transition (e.g. how to help people who are at risk of seeing their skills rendered obsolete) and (2) with social problems, wherein a significant portion of our population is getting left behind in terms of life, education, and job skills necessary to ride the wave of high-productivity, modern jobs.

But my fundamental outlook is based on optimism about making the future work for us. Not pessimism about trying to prevent companies from modernizing and automating. Also, I think a lot of the automation talk is overblown. There’s a long, long way to go between computers being able to kind-of, sort-of do a human’s job under controlled laboratory conditions and computers actually being able to efficiently displace humans. Flipping burgers is one thing .Sophisticated manufacturing (like at SpaceX) or software engineering (anywhere) is another entirely.

You’re right that automation has been going on for hundreds of years in various forms. However, since the invention of the computer, the pace of automation has accelerated dramatically.

You have a bit of a false sense of security when it comes to jobs being replaced by computers. Just because a computer can’t replace a person in the Turing test (which is debatable at this point, but we can still call that “far off” for the sake of this argument) doesn’t mean that computers can’t replace people. A substantial proportion of all new advances in computers, or in software for that matter, replaces some small portion of need for human labor. Yes, sometimes new labor opportunities are also created, but these are often non-essential opportunities. The tasks that need to be accomplished become easier and easier, requiring fewer and fewer people (jobs) to get them done, and the opportunities that open up are non-essential. Disruptive technologies, are, first and foremost, disruptive.

Interesting that you mention SpaceX. Do you know how much smaller SpaceX is than NASA was at its height? That’s not due to corporate efficiency. That’s technology replacing people.

That doesn’t mean I think you’re off base entirely. I’m just trying to point out that the problem is so much deeper in the system than we want to believe. There are no quick fixes. You can alleviate the suffering of people or corporations, but until we are looking at the broader issue, everything is, at best, a temporary fix.

Tyler-

This is an objective claim about the past, and it seems to be pretty clearly false. For instance:

Since computers are old now (modern computers go back at least to the 1940s), there has been plenty of time for permanent job loss to have been evident by now, and yet a leading research says that there not only isn’t a faster rate of job loss, but that there is no historical evidence of any long-run job loss caused by technology at all. The quote is from an article called How Technology is Destroying Jobs, so it actually does take your position about future predictions, but it doesn’t support your assertions about present or historical trends.

I don’t think it’s a false sense of security. I have a masters degree in systems engineering (also economics, btw) and my day job is in a software development company. I’m pretty familiar with the intersection of computers and work. And I’m also very familiar with exaggerated claims about how close we are to big breakthroughs like passing the Turing test. Which, no: we’re not close. You might be thinking of news stories from this summer that a computer had passed. They were wrong. Passing the Turing test is like flying cars or jetpacks: it’s been just around the corner for 70 years. There’s even an xkcd comic about the phenomenom. The hover text for the comic is:

As for the argument that new advances replace labor: they don’t. They displace labor. Going back to the 1700s, we lost jobs in one sector and found them in another. Demand for software developers has never been higher, and the same is true of data analysts. The entire ecosystem of Big Data only exists because of advances in computer progress. The problem is not that jobs are disappearing in aggregate. It’s that they are disappearing from one sector and then appearing in another sector.

Actually, the opposite is true. It’s menial, repetitive tasks that get elminated. Which means, by definition, that the jobs which are left tend to be non-physical, intellectually challenging and–because they use automation where possible–highly productive. This has been true since the 1700s. We lost agriculture. We gained white-collar professions. This is an improvement. The jobs eliminated by computers are almost always the kinds of jobs that no one would ever want to do if they had a choice.

The focus of our policy should be on helping them have a choice.

Sure, a lot of it is technical efficiency. But (1) because their manufacturing is so high-end, it is still bespoke. Custom. Highly labor-intensive. You can’t make spaceships on an assembly line, and that won’t change any time soon. More importantly, however (2) there was no private space industry at all before. SpaceX didn’t disrupt NASA. NASA got eviscerated for political reasons. SpaceX jobs aren’t an example of shrinkage, but expansion. The entire private space industry is a new industry.

Here’s the recap:

We’ve got three centuries of data that say technological progress does not kill jobs in aggregate. It only kills specific industries (usually menial labor) while creating new ones (usually white collar). The idea that technology is about to permanently destroy our economy by removing jobs in aggregate is not a factual statement about the past. It is an assertion about the future. It’s an assertion that is founded in overly optimistic ideas of what jobs a computer can do and ignoring the jobs that are created by automation.

We are in for a very rough ride because a faster pace of tech change means faster disruption. But disruption is disruption. Not destruction. The primary problem is managing change, not bracing for some kind of job apocalypse.

That’s a more thoughtful response than calling minimum wage raising “foolish” and “objectively dumb.” Raising the minimum is probably better than the current practice of doing nothing, but worse than many other options.

Given that EITC amounts are tied to inflation, tying the minimum wage to inflation seems to make just as much sense. Raising it in big, unpredictable steps is maybe the worst way to do it.

Ryan-

Meh. There’s all kinds of nuance in an academic / theoretical discussion. But advocating to raise the minimum wage isn’t an academic / theoretical discussion. It’s a policy discussion. And, in terms of policy, I stand by my characterization of the minimum wage as both foolish and objectively dumb.

FWIW, I’m trying to be nice. The other alternative is that it’s nefarious and cynical because it pits a popular policy against the interests of those the policy is supposed to help.

Economically speaking, this analysis is incorrect. If the hikes are unpredictable and short-term, you wouldn’t expect corporations to respond with massive investments in automation. As a result, the negative impacts on employment are minimized. If you tie it to inflation, the predictability of the hikes and their long-term duration will make automation much more palatable, and the impact on jobs will be far, far worse.

Quick note: I just turned threaded comments off. So you can now no longer reply to a comment. That may make this thread a bit more confusing.

(I turned them off because in theory they work, but in practice we didn’t have enough comments to justify them. Especially when they were limited at only 5 levels deep, and we ran into that pretty regularly.)

If payroll expenses are likely to take a huge jump in the near future, corporations are LESS likely to make a huge investment in ways to mitigate that huge payroll jump? The opposite would seem to be true. If there’s 25% chance I’m about to be hit very hard, I’m taking big actions NOW to mitigate that. If the hit never comes, I’m now poorer but better prepared for the inevitable, eventual hit.

A converse example: If payroll expenses are expected to climb at a known rate, a steady offsetting of those expenses (through automation) seems like the logical response.

Big risk, big defense. Known, small risk: steady mitigation.

In any case: Automation is inevitable so adding it will only be an issue in the short term (e.g: until all the grocery lines are self-checkout). Worrying about an issue that’s likely to only affect wages for a few years seems like a distraction.