One common atheist argument is that you should disbelieve in God because there is no evidence of God. The argument is commonly made by analogy to other mythical creatures like the tooth fairy or the flying spaghetti monster or a celestial teapot. There’s no evidence of the tooth fairy, but that doesn’t mean that we’re neutral about the existence of tooth fairies. We’re pretty sure, based on the lack of evidence, that they do not actually exist. Here’s Richard Dawkins making this case:

It is often said, mainly by the ‘no-contests’, that although there is no positive evidence for the existence of God, nor is there evidence against his existence. So it is best to keep an open mind and be agnostic. At first sight that seems an unassailable position, at least in the weak sense of Pascal’s wager. But on second thoughts it seems a cop-out, because the same could be said of Father Christmas and tooth fairies. There may be fairies at the bottom of the garden. There is no evidence for it, but you can’t prove that there aren’t any, so shouldn’t we be agnostic with respect to fairies?

The problem with this argument is that it seems to contradict basic logic: lack of evidence is not evidence of lack. And yet the intuition seems solid. We don’t merely not believe in the tooth fairy, we actually disbelieve in its existence.[ref]Non-belief refers to the absence of belief. Disbelief is a belief, but a negative one. It’s belief in the proposition that a thing is not true or does not exist.[/ref]

Most people either write off the “lack of evidence isn’t evidence of lack” line as a kind of irrelevant technicality or try to treat disbelief as something other than a form of belief. These approaches are sloppy and incorrect, and they create a warped skepticism in which negative beliefs are given an irrational and unearned privilege over positive beliefs. That’s not real skepticism, it’s just inverse credulity combined with dodgy semantics. It makes a mockery of the proud tradition of philosophical skepticism by creating a mirror image of blind faith. In the old days, the existence of God was accepted without proof. These days, a kind of hostile disbelief in God is accepted without proof instead. Meet the new orthodoxy, same in process and approach as the old orthodoxy.

Luckily, however, there actually is a way to reconcile our intuition that we should be skeptical of the tooth fairy (not merely neutral) with the rules of logic. The term that comes to the rescue is compossibility. This is a term I learned from reading an incredibly great sci-fi book[ref]Anathem by Neal Stepehenson, which has nothing to do with this post but you should definitely read.[/ref], but the term originates with Leibniz. From Wikipedia:

According to Leibniz a complete individual thing (for example a person) is characterized by all its properties, and these determine its relations with other individuals. The existence of one individual may contradict the existence of another. A possible world is made up of individuals that are compossible — that is, individuals that can exist together.

Let’s take a look at how the concept of compossibility can be used to provide a solid rational backing for the intuition that the tooth fairy doesn’t exist without requiring us to contradict the principle that lack of evidence is not evidence of lack. Except, instead of a tooth fairy, I’m going to go with the proposition that there’s an invisible unicorn in your backyard.[ref]The reason? That’s actually the example that, many years ago, prompted all these thoughts. And unicorns are intrinsically kind of funny.[/ref] Now, should you have:

- Belief | You think that there is a unicorn.

- Non-Belief | You do not think that there is a unicorn.

- Disbelief | You do not think that there is a unicorn and you think that there is not a unicorn.

Here’s how compossibility comes to the rescue. A unicorn is basically a horse with a horn on its head. Horses are large mammals. If you had a large mammal in your back yard then, even if we concede it’s invisible, it would still leave hoofprints and unicorn poo behind, and it would probably also be rather noisy. Do you see any hoofprints? Smell unicorn poo? Do you hear a large 4-legged beast walking around and breathing heavily? Nope? Then you don’t just have a lack of evidence. You really do in fact, based on compossibility, have evidence of a lack. These things should be there, and they are not. Therefore, the invisible unicorn is not compossible with the state of your backyard (e.g. free of unicorn poo).

Now, I might tell you that the reason there are no hoofprints and that there is no unicorn poo is that the unicorn is actually not just a horse with a horn on its head. It’s a magical creature that only looks like a horse. In fact, however, it is light as a feather (no hoofprints) and subsists on love (no material food, ergo no unicorn poo). This new definition of an invisible unicorn is more compossible with the state of your backyard (hoofprint and unicorn poo free!), but it’s actually not more believable because now it’s asking you to believe other things that are not compossible with your experience of the world. Where, if invisible unicorns are common, do the dead ones go? Why aren’t people stumbling and falling over invisible unicorn corpses? Or hitting them with their cars? And if they are rare, how do they keep up a viable breeding density? And if they don’t breed, where do they come from? Etc.

These questions are, of course, all a bit absurd. The point is that our human intuition is, generally speaking, pretty good at doing this kind of analysis unconsciously and quickly. You don’t really need to go through all the specific questions. You can just take the basic concept of a unicorn and see that such an animal remaining undetected is highly improbable. So you’ve got a good reason to suspect that if there’s no evidence then it actually is not present. The more the definition gets altered to make the lack of evidence seem credible, the more the definition itself becomes incredible. You start asking where the unicorn poo goes and you end up asking questions about the thermodynamics of a creature that converts love to kinetic energy to move its body.

So our disbelief in things like the tooth fairy doesn’t come from what we don’t know. It comes from what we do know. It comes from everyday knowledge about biology and human nature and physics. Skepticism of things like invisible unicorns or flying spaghetti monsters or celestial teapots is not properly rationalized by knee-jerk preference for disbelief, but by deliberation about compossibility.

So how does this apply to the real argument at hand: the existence of God? I’m not going to try to convince anyone that God is real using compossibility. I’m just going to differentiate between good arguments for the non-existence of God and bad arguments for the non-existence of God. Bad arguments might take the form of, “Well, there’s no evidence so we should disbelieve.” That’s not a logically sound position to take. It’s just prejudice wrapped up in rational terminology. The argument is bad both because it’s a poor argument but also because it just doesn’t lead to any productive thought or discussion. It’s a waste of everybody’s time.

But a very good argument for the non-existence of God is to rely on something like the Problem of Evil. This turns out to be a compossibility argument again: how are (1) an all-powerful God and (2) a benevolent God and (3) the crappy state of affairs here on Earth all compossible? Just like skepticism of the invisible unicorn in your backyard, skepticism of a benevolent and all-powerful God based on the injustice and miserable suffering on Earth is a skepticism with reason behind it. Such skepticism is good both because it’s logically stronger, and also because it can lead to useful discussion.

Very interesting, thanks for writing. I think a lot of people who say “there’s no evidence” are using a shorthand to say “God is not compossible with our universe” because, like me, they probably have never heard the actual word “compossible” before now. But as I read your questions about invisible unicorns and thermodynamics they reminded me of questions skeptics bring up about the physical possibility of miracles like the resurrection (is that supposed to be capitalized?)

In other words, I think a lot of people who assert “there’s no evidence” are actually doing the quick, unconscious kind of analysis you mentioned and just not articulating it well. It might be sloppy language but I think most of the time there’s more reason behind it then just a knee-jerk reaction. I’ve seen so many people follow “there’s no evidence” with “if God did exist, XYZ thing should be happening, and it isn’t.” That’s the same kind of thought process as your unicorn thermodynamics, right?

Monica-

Yeah, I definitely think that a lot of the atheist arguments are intuitively relying on compossibility. So the point of my post was absolutely not a counterargument against those intuitive claims. But I do think it’s important to get the logic right, because otherwise the conversation can be hopelessly muddled. This is especially true for someone like Richard Dawkins, who has sort of built a career out of being a posterboy for rational skepticism.

It goes to my bigger belief that sometimes how we argue is much more important than who seems to be winning. Ultimately, we’re never gonna know who is right and who is wrong. We don’t really have control over that. But we do have control over trying to be rigorous and careful and productive in our debates.

The goal of this post is to serve that end.

An associated goal is to try and remove what I think is an unearned rhetorical advantage that those critiquing religion (not all of them) sometimes rely on, which is the semantic trickery of conflating non-belief and dis-belief. They are two distinct concepts, and confusing them isn’t a neutral mistake. It’s very, very convenient for the side that wouldn’t mind at all if they could create a relatively weak argument for non-belief in God and happily end up with a much stronger conclusion for dis-belief in God.

But, at most, this post resets the conversation a bit. It makes zero attempt to actually construct a pro-theistic argument or rebut any of the many quite serious and quite rigorous anti-theistic arguments.

Not to complicate your argument, but…

http://www.iflscience.com/plants-and-animals/rare-unicorn-deer-found-slovenia

lolz, thanks for that contribution, Nate! :-)

Nathaniel,

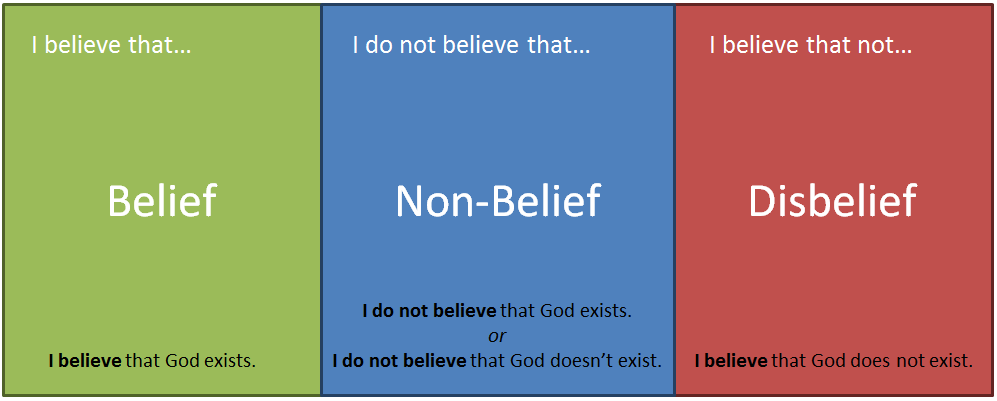

Why in your model is Disbelief a subset of Non-belief? If Disbelief is a kind of belief, then surely it is a subset of Belief?

Jeremy

Jeremy-

Your question was a very good one. I could tell you why I originally went with the illustration that I did, but after giving it some thought I decided it would be better to just replace the illustration with a better one that avoids the problem entirely. So, you can see the updated image above and the note that you’re the reason I changed it.

Thanks for the great comment!

“The more the definition gets altered to make the lack of evidence seem credible, the more the definition itself becomes incredible.” I’d be interested in an exploration of the idea of incredible definitions. I’ve seen many atheists express exactly this frustration with the Christian God–that, every time God gets disproven, the idea of God has changed just enough to avoid that particular disproof. Even God’s greatest supporters would presumably agree that he seems pretty incredible–miraculous, even.

Worse, the appeal to mystery which happens so often seems to be a denial of compossibility as a legitimate standard. The suggestion that atheists ought to rely on compossibility arguments rather than shifting the focus to a more muscular sort of non-belief as a default position seems sort of unfair if the game is just to pull that rug out from under them once they obey. I don’t mean to attribute that move to you, but it’s clearly common (I have, for example, never heard an explanation of the trinity which didn’t sound like straightforward nonsense) and likely behind the search for an argument which might stick. Since Christians generally disbelieve in the gods of other religions, it seems as though searching for the reason for that and holding up a mirror is a fair and promising option.

“Since Christians generally disbelieve in the gods of other religions, it seems as though searching for the reason for that and holding up a mirror is a fair and promising option.”

This is an argument that I have been turning over in my head. How can Christians make an appeal to mystery without allowing other religions to explain away logical or philosophical problems with ‘it’s a mystery’? I don’t really a solid answer, but I keep in mind that a God who is at least in some ways beyond human knowledge and reason makes more sense to me than a God completely understandable in human terms because the latter is likely a god made in our own image while the former matches what we would expect of a perfect, transcendent being who exists outside the material universe.

As to the nitty gritty of comparative claims, though, I think much of accepting the mysteries of a particular religion is going to derive from seeing the logic and evidence of the other claims we can and have investigated, and if the religion has a good track record, we’re more likely to consider accepting its mysteries. So I would suspect that the Christian trinity, for all it’s difficulty to make sense, continues onward because Christianity has a long tradition of applying reason and philosophy while the fairly straightforward Greek gods fall by the wayside because, for all their ease of understanding in purely human terms, applying any amount of logic and philosophy to them reveals they’re nonsense.

“I have, for example, never heard an explanation of the trinity which didn’t sound like straightforward nonsense”

Relevant: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KQLfgaUoQCw

Honestly, the FSM/teapot argument works best against a physical God that is (in some sense) within time and space like the one found in Mormonism. When it comes to classical theism, then the blunder of the atheist response is metaphysical. Classical theism does not see God as *a* being among many, simply Supreme. It sees God as Being Itself. As David B. Hart explains,

“The most venerable metaphysical claims about God do not simply shift priority from one kind of thing (say, a teacup or the universe) to another thing that just happens to be much bigger and come much earlier (some discrete, very large gentleman who preexists teacups and universes alike). These claims start, rather, from the fairly elementary observation that nothing contingent, composite, finite, temporal, complex, and mutable can account for its own existence, and that even an infinite series of such things can never be the source or ground of its own being, but must depend on some source of actuality beyond itself. Thus, abstracting from the universal conditions of contingency, one very well may (and perhaps must) conclude that all things are sustained in being by an absolute plenitude of actuality, whose very essence is being as such: not a “supreme being,” not another thing within or alongside the universe, but the infinite act of being itself, the one eternal and transcendent source of all existence and knowledge, in which all finite being participates.”

Nonetheless, I think one can make a rational argument for the existence of a Supreme Being that is not equated with Being Itself. This has been called “theistic personalism” by some philosophers of religion and many philosophers actually fall into this camp perhaps without even realizing it. I actually think many philosophical arguments made by the likes of William Lane Craig and Alvin Plantinga actually work somewhat better in a Mormon paradigm that fully embraces a personal, embodied, impassioned God.

First of all, Anathem is fantastic. Highly recommended.

I always took the teapot analogy as pushing the burden of evidence back where it belonged, on the person making a positive claim. We rationally assume the null hypothesis, and a claim as extraordinary as God requires extraordinary evidence. All this believe-not vs not-believe business sounds like a Johnnie Cochran defense.

I appreciated Walker’s comment distinguishing a metaphysical God vs the Mormon description of God as more discrete. The teapot analogy doesn’t stick to the metaphysical God, which is just a God-of-the-gaps. If someone did believe in such a God that is manifested as the laws of physics, I have a hard time seeing why someone would worship it. Ignoring the positive placebo effect of worship on the worshiper, it makes as much sense to worship a subway map or a stop sign. Yes, it helps things stay organized and run well, but I doubt the map cares what you think of it.

Nathaniel, I like the framework you present.

You apply it to unicorns, but how would it work with ghosts?

There’s no established standard as to whether ghosts might reflect, emit, absorb or scatter visible wavelengths, whether they could interact with other EM frequencies, produce sound waves, create temperature differentials, levitate white sheets, etc.

This makes it hard for me tie my own perceived lack of evidential support for the existence of ghosts to a demonstrable failure of compossibility between ghosts and my model of the world. Am I therefore engaged in irrational disbelief, rather than justified non-belief?

I might be raising a similar question to Kelsey Rinella – how do we address the distinction between disbelief and non-belief where the definition of a particular phenomenon are inconsistent or not well established?

Kelsey-

So… partially your comment is moving beyond my central point, which is really just about clarifying the terminology of the debate and resolving an apparently logical problem, and on to the main event: an argument about the existence of God. I’m sympathetic to your criticisms on that score, but I’m not really in a good position to address them because I don’t think I rely very much on the pro-theistic arguments you’re annoyed with. Like mystery. Mystery is not really a big part of my religious world-view, except as a sort of catch-all for “stuff which I do not yet get.” I’ll give this some more thought, but I don’t think anything in my belief in God relies in any way on non-understanding / mystery. For folks to do that would, at least at first glance, seem rather silly. That’s not to say that I don’t think mystery has any role to play, but for me it would not have much of a role when it comes to faith itself.

Also, I think debating about the Trinity is silly. Don’t Debate the Trinity because, as you said, no one has any clue what they’re talking about.

Fundamentally, your question seems to be, “OK, I’ll grant the setup in general, but what definition of God are you relying on?” Good question. I have my own definition, which I will share in subsequent posts.

Ryan-

The key point is that the claim “God does not exist” is a positive claim. That’s pretty incontestable. So before we even get to questions about who has a greater burden of evidence, the key point is that any position other than neutrality has at least some burden of proof. Want to convince someone that God exists? OK, you have a burden of proof. Want to convince someone that God does not exist? OK, you have a burden of proof. Any attempt to state that the default is disbelief is an invalid semantic trick.

This isn’t academic because, as Dawkins’ quote points out, very prominent atheists do in fact rely on this semantic sleight of hand. And they ought to be called for it.

Having made that point, however, it remains true that arguing for theism does require a great deal of evidence. I’ll grant you the whole “extraordinary claims…” mantra. You ought to keep in mind, however, that there’s also the incredible difficulty of trying to prove the non-existence of a thing. What’s the trade off between the believer’s burden (extraordinary claims) and the disbeliever’s burden (non-existence proof)? I don’t know, and I don’t really care. The fundamental point is that they both have their work cut out for them.

In the meantime, the default resting position is neutrality. I don’t mean that’s where we should remain until we prove one side or the other. I just mean that ought to be the starting point. There are plenty of good arguments (e.g. the Problem of Evil) that give people a reasonable basis to move along the spectrum towards disbelief. I’m not at all arguing that anyone is unreasonable for disbelieving. Nor, in this post or as a general rule, am I trying to argue against that position.

It’s just worthwhile, in my opinion, to be a bit more careful about how one gets there.

Seb-

Well, I think one thing you get right immediately is the idea that you have to nail down a definition of “ghost” before it makes sense to talk about believing or disbelieving in them. Here’s how one argument could possibly go: if there really was a singular class of entities called “ghosts” that had a common set of attributes, then people’s stories about those entities should be fairly uniform. Since they are not, I do not believe that there is likely to be a single class of entities we could call “ghosts.”

That’s a compossibility argument, and I think it works. But it’s not very conclusive. Maybe there are lots of different types of things we could call ghosts? Who knows?

The two points to make:

1. Intuition is usually a good rule-of-thumb. There are too many questions for us to deliberate consciously about all of them. When we decide a question is worth our time, then it makes sense to analyze our intuition rationally and see if it is sound or if we’ve got a hidden assumption that makes it unsound, etc. That’s what I’m mostly doing in this post: providing the rational framework people can use to gauge their intuitions about questions like the existence of God, UFOs, unicorns, ghosts, etc.

2. I honestly don’t care that much about ghosts. That makes it easy to maintain a large degree of neutrality on the topic. Now, there’s a very strong social pressure in our community (educated Westerners, let’s say) to distance oneself from “silly” beliefs: ghosts, UFOs, conspiracy theories, etc. But it’s important to separate a rational rejection of those things from social convention.

Example: I disbelieve in conspiracy theories as a general rule because they are not compossible with my understanding of human nature. Very quickly: people just aren’t that good at keeping secrets, maintaining group cohesion, acting against their own self-interest, and exerting high degrees of control and coordination in a complex, random world. All of these attributes are necessary to believe in most conspiracy theories. None of them seem plausible, so I have active disbelief in most conspiracy theories. But I also admit that being able to say that makes me breathe a sigh of relief because I know people in my social circles would look at me very strangely if I were a conspiracy theorist. The rational decision and the social decision correspond, and that’s easy and fun.

The question we have to ask ourselves, if we want to have any chance of being more than mere expressions of our cultural zeitgeist, is whether we’ve got the fortitude to buck the social pressure and follow our rational decision in the (rare, most likely) cases where we think that the common wisdom is wrong.

So, how much of the general disbelief of right-thinking people (educated Westerners) is from a sound compossibility argument and how much is from social convention? That’s, I think, an even more important question then whether or not ghosts (whatever that word) actually exist.

Just to clarify.

When you said

I got a little confused at the seeming restatement of the first portion of #3 after the “and”. Does “You do not thing that there is a unicorn” mean you do not think that there is a unicorn in your backyard? Really just a reference to the location of one such magical creature.

The second portion of 3 reads “you think that there is not a unicorn.” Does this mean that you do not believe in the existence of the unicorns in general?

Thanks,

It’s not quite that I’ll grant your setup, it’s that I think your setup yields a pretty good model for what you’re trying to say, the argument you criticize does the same for what they want to say, and neither of them perfectly reflects the underlying beliefs. They’re just pretty good shortcuts.

When I describe my atheism, what I say is that I think it would be epistemically irresponsible for someone with experiences like mine to believe in any god. I think a nice way to meet your point would be alter that to “It would be epistemically irresponsible for someone with experiences like mine to behave as though there is a god.” Because there are virtually no behaviors which follow from atheism which do not also follow from non-belief. Belief in God, or really anything supernatural, virtually never occurs in the absence of some specific beliefs about it. The closest I’ve ever encountered is a deist, who think a god exists and created the universe, but doesn’t know anything else about this god. She is very often mistaken for an atheist.

I suspect that atheists who make the claim that disbelief is the default really believe something more like this. They may see the difference between disbelief and non-belief as of no practical importance, and think that our epistemic duty is to avoid acting or withholding action because of credence given to entities of which we have no evidence. Indeed, they might well regard those who deny disbelief but claim non-belief as slightly deceptive, for it isn’t merely that they lack belief in God, usually they’re also saying they hold the idea of God in higher esteem than the ideas of other undetectable things. You can draw the lines so as to group these people with people who never entertain the idea of God if you like, but that groups those to whom Pascal’s Wager might make sense with those to whom it generally wouldn’t, so you’d expect more diverse behavior in that category than a category which included anyone who really behaved as though there was no evidence for God.

Matt-

Yeah, the three options are about the specific thought experiment of the unicorn in your backyard. You either believe that there is one there, believe that there is not there, of have no particular beliefs about the existence of a unicorn in your backyard at all.

Technically, you could believe that there are unicorns somewhere else, but just not in your backyard. But that’s not really the point of the example, since pretty much all the arguments about the unicorn in your backyard can be extrapolated (with minor changes) to unicorns anywhere on Earth.

Kelsey-

Then I guess I misunderstood you. Could you explain what “they want to say” refers to in this case? Both the “they” and also the “what they want to say” bits?

I don’t think that my position is incompatible with your statement, since you seem to be expressing non-belief as opposed to disbelief in God. You say you don’t/shouldn’t believe in God’s existence. That’s non-belief. You might also so that you do/should believe in God’s non-existence, but (unless and until you do), our positions seem perfectly compatible.

Now that is something that I am trying to push back against. First of all, I think that there are considerable differences in behavior that result from non-belief and disbelief. For example, nothing the New Atheists do is compatible with only non-belief. You have to be pretty confident in a positive belief in God’s existence to make any sense of the New Atheist agenda whatsoever.

Secondly, I also just think that attitudes matter, and you could make a case that an attitude is separate from a behavior. Even when the external behavior of a nonbeliever and disbeliever coincide (i.e. they both go somewhere other than church on Sundays), their feelings about that behavior could differ quite widely. A nonbeliever may, for example, be more tolerant of a believer and a disbeliever than the believers and disbelievers tend to be (respectively) of each other.

In short: I think that conflating disbelief and nonbelief is a subtle but very important way for disbelievers to rig the discussion.

Last point:

You can’t avoid action and avoid inaction at the same time. That’s a logical impossibility. This is exactly the kind of problem that I see with the campaign to conflate nonbelief and disbelief. It’s all rhetoric and semantics. It doesn’t actually make any sense at all. You could just add a negation to every term in the whole debate and have a society where everyone thinks that nonbelief and disbelief in God’s non-existence is the same, and it’s the belief in God’s non-existence that has a burden of proof is weird. After all, aren’t atheists who say that morality doesn’t depend on the existence of God in effect stating that there’s no significant behavior difference between non-belief and belief in God?

Here’s what’s really going on: the conflation of non-belief and disbelief is really nothing but an expression of the prevalence and social dominance of disbelief. Period. Just as individuals come up with their conclusions first and then rationalize them second, society is doing the same thing. We live in a society where disbelief is increasingly ascendent, and conflating non-belief is just a way of providing a rational justification for that position.

I think the new atheists want to make the point that you don’t have to treat epistemically irresponsible beliefs which might be true any differently from epistemically irresponsible beliefs which you know to be false. What justifies our treatment of a belief isn’t its truth or falsehood, but the adequacy of its justification. Lumping non-belief and disbelief into a single category helps make that point seem intuitively plausible, while dividing them makes it seem artificial.

You seem to think that your division is natural, and tracks our intuitive understanding better than the new atheists. That isn’t true for me–I don’t even know whether I believe in God’s non-existence, as you use that phrase. My first reaction is to go into more detail and let you figure out whether I fit that category or not, because it’s so unfamiliar to me. That may sound very strange, but I’ve largely relegated talk of belief to when I’m being brief–for a long time, when I’ve tried to be careful, I’ve spoken in terms of probabilities or, even better, what actions I’d take. So, to me, it looks as much like you’re trying to rig the discussion to provide a wedge as it does like they’re trying to rig the discussion to obscure a genuine difference. While I find their methods boorish and their characterizations often unfair, I regard myself as sympathetic to the new atheist project of reducing taboos against treating religion like any other ill-founded and improbable belief. I just think I’d like to be nicer to people who think, as one absolutely charming former co-worker of mine did, that our restaurant was inhabited by angels. Intellectually, I regard such claims as not worth consideration until some evidence for them is available to me. We don’t generally give any such claims serious consideration, but the “no-contests” seem to treat religious claims differently from non-religious ones.

You suggest that we have evidence that the Tooth Fairy isn’t real, we don’t just have no evidence. Fine; think of something which is a better fit. Say, that there is a person standing behind you right now about to murder you, but whom you simply haven’t noticed yet. For most of us, that’s technically possible, but to actually give it serious consideration would be regarded as unreasonable; even trying to make a distinction between whether you believe there is no murderer behind you or merely lack a belief in such a murderer would seem like a deliberate attempt to undermine reasonable epistemic policies. It’s more practical to dismiss such thoughts entirely either way, which seems to me to be what the new atheists are suggesting with their division. I expect the ways in which this analogy strikes you as problematic to be informative to me.

My apologies for the action/withholding action unclarity. What I meant was that the new atheists think our epistemic duty is not to allow credence given to entities for which we have no evidence to direct either acts (e.g. banning abortion) or refusals to act (e.g. refraining from criticizing religious beliefs in the same way we’d criticize non-religious beliefs which are evidentiarily similar).

My understanding for the FSM, unicorns, and fairy analogy has always been one to use for a simplistic comedic response. Most people (including myself) have such a tiny understanding of epistemology that going much deeper into these types of debates is rarely productive. Discussions about beliefs aren’t new and still inconclusive, just ask these peeps: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_epistemologists.

I would agree that Dawkins has a disbelief in the FSM not a non-belief, but it’s the point he is making that is being missed. Which is to show how theists argue the difference between god, gods, unicorns, and fairies. It still doesn’t make sense to me. People believed in fairies and still believe in fairies. http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/s/silver-strange.html. Greek Mythology wasn’t a myth. Are you saying people are absurd for believing in more than one god, unicorns, or fairies?

“These questions are, of course, all a bit absurd. The point is that our human intuition is, generally speaking, pretty good at doing this kind of analysis unconsciously and quickly. ”

If so, than you are an apolydeist, aunicornist, and an afairiest.(not even real words to describe these things). It’s fun to have these type of labels, right? To these people your arguments would probably seem like “hostile disbelief”.

As an atheist I find it frustrating that requiring objective evidence of a God makes my position seem hostile or I need some philosophical argument to make my disbelief valid. I haven’t seen a need for God in my world view, so I don’t include one. If there was objective evidence of a God I would adjust my world view. Many friends and family see a need for God in their life, so they include one. Just like some people that need gods, fairies, and unicorns. That’s why the analogy works, because the same amount of evidence exists for a God, FSM, or fairies.

LB-

So, my point has two main points. The first is pretty simple: you shouldn’t believe something without a good reason.

Rationally, I think this position is basically unassailable. Believing something when you don’t have a good reason is basically the definition of being unreasonable, right? So I’m really just saying: don’t be unreasonable.

Emotionally, however, it’s not a natural position to take at all. That’s because a fundamental human drive is to eradicate ambiguity and certainty and to find meaning and clarity. In one sense, that’s all we’re ever really doing. We take in raw, disjointed data and we turn into pictures (visual perception) and narratives (self-perception). That means that emotionally we like to have a starting point. A foundation. Something to start with.

It’s psychologically appealing, but it’s not rational.

The second thing I’m doing is trying to expand what it means to have “a good reason” to believe something. Science has become so dominant in our society, that we have a real risk of using scientific ways of knowing (technically: positivism, if you’re curious) and treating it as the only way to know something. So people jump right to concepts like “objectivity” or “evidence” without realizing how limiting they are. Consider your post, for example:

That’s basically an appeal to pragmatism. And I’m OK with that. I like pragmatism a lot. That’s one basis for belief that is completely non-scientific, but still valid. So there’s one alternative. Another alternative is the “compossibility” idea that I brought up. It’s kind of a cousin of falsifiability (there’s positivism again), but not quite the same thing. We could debate about whether or not it’s scientific, but if it is it’s clearly at the margins, not something central like objective, quantifiable evidence from a repeatable, controlled experiment, right?

So those are my two basic points:

1. Don’t believe in a thing unless you have a good reason.

2. Good reasons include scientific evidence, but also additional approaches like compossibility and pragmatism.

Refuting God based on lack of evidence by comparing God to the tooth fairy, as Dawkins did, is just loading the dice. My response is to try and make an even playing field. That’s why nothing in my post argues for or against the existence of God. Just for thinking about it a little bit more clearly.

Kelsey-

I’m not sure what to make of this, since if we’re assuming the beliefs in question are “epistemically irresponsible” (I do like your notion of responsibility, by the way) then it seems like the work is already done. If believe in God is “epistemically irresponsible” then it doesn’t really matter to me whether we say it “might be true” or if it’s something we “know to be false.” The argument seems over before it started.

Don’t get me wrong, I think that is kind of what they’re doing. As I wrote to LB: they’re loading the dice.

1. People don’t believe in the tooth fairy because there is no evidence.

2. There is no evidence of God either.

C. So, to be consistent, people shouldn’t believe in God.

The first problem is that “don’t believe” is too general. It includes non-belief and dis-belief. That–if you’re an strong atheist who affirmatively believes God doesn’t exist–is absolutely loading the dice. No question. You’re associating your position with a position that is much easier to defend.

So it should be written as:

1. People disbelieve the tooth fairy because there is no evidence.

2. There is no evidence of God either.

C. So, to be consistent, people should disbelieve God.

Well, now we’re being clear, but the problem is that #1 isn’t true. I think people disbelieve the tooth fairy out of intuitive ideas of compossibility. But if you say that people do disbelieve the tooth fairy merely ’cause of lack of evidence, then you’re violating the basic principle that you ought not believe anything (disbelief is a kind of belief) without a good reason. And lack of evidence isn’t a good reason. At least, not all by itself.

But hey, my shorter point is this:

It’s not at all contradictory for someone to disbelieve the tooth fairy and still believe in God. Especially if, you know, you’re a parent. :-)

That makes it more clear. I appreciate your response.

But, I don’t think compossibility is a good reason. It’s interesting to think about – but not a good reason, in my opinion. I guess that is one of our philosophical differences. Philosophically I’m agnostic (non-belief) and accept that there are just some things we can’t currently know – God included. But when it comes to theism, I’m atheist in the way that you are aunicornist (disbelief) and we both have our reasons. Either we are both being reasonable or unreasonable – I’m unsure which it is. :)

I think Dawkins is far from loading the dice. It actually levels the playing field because it gives all people the same level of access to knowledge and evidence.

The problem is when someone assumes that they KNOW something that others don’t know or can’t know, like God. IA person can come up with a lot of good reasons, or what they think are good reasons, to believe in something – but, so what? Good for them? Unless of course their beliefs can hurt others, which happens all too often.

Being agnostic philosophically does work with my brain and emotional stability. Ambiguity works for me. When I dropped the whole meaning to life thing, it brought happiness. Why? Because I stopped looking for knowledge that can’t be found right now or the meaning of life and instead turned to learning about what can be known. I found a fascinating universe with a vast amount of knowledge that I will never be able to consume in my lifetime. That’s freakin awesome and meaningful to me.

I must also find it engaging to read your blog and discuss. :)