Let me start with a great blog post from G. at Junior Gaynmede: Have You Ever Heard of Plato, Aristotle, Socrates? Morons.[ref]That’s a Princess Bride reference, in case you missed it.[/ref] Here are a couple of excerpts to whet your appetite for this excellent post:

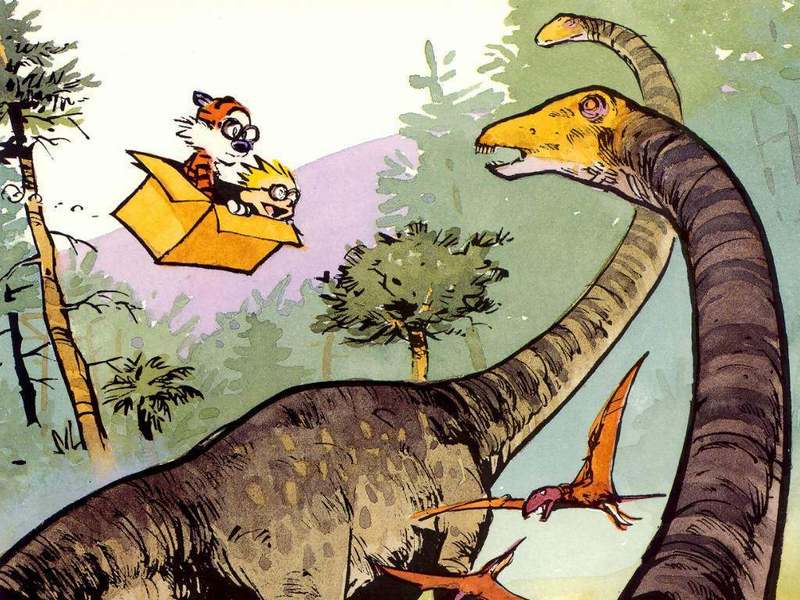

Calvin and Hobbes is one of the great works of Western civilization. I don’t know if it will still be read and loved centuries into the future, but if not so much the worse for centuries into the future. Centuries into the future ought to write “Time Machine” on the side of its cardboard box and zoom back here for some of the good stuff.

And also:

Christ made childishness one of the great questions of human existence. Following him, we now know that it is of the stuff salvation is made of. For the Christian, childhood is part of the Great Conversation and Calvin and Hobbes is a classic work. It’s silliness is soulcraft.

I want to extend that last paragraph just a little bit and talk about Lazarus. I taught that story in Sunday School on Sunday, and two verses in particular stood out to me as I taught it. They have stayed with me since, as well, orbiting my mind with the insistence of gravity and physics, demanding constant attention. Here they are:

39 Jesus said, Take ye away the stone. Martha, the sister of him that was dead, saith unto him, Lord, by this time he stinketh: for he hath been dead four days.

40 Jesus saith unto her, Said I not unto thee, that, if thou wouldest believe, thou shouldest see the glory of God?

The contrast between Martha’s concern about her brother’s rotting corpse and Jesus’ promise to see the glory of God strike me as profound. It seems to me that nothing that actually matters in life can be grasped directly. If you wish to mold your character, you must do so indirectly, by policing your thoughts and actions. If you wish to spread the Gospel and preach, you can use your words and actions, but they will never be more than a vehicle through which the Holy Spirit may–or may not–be conducted. If you wish to experience love, you cannot do so directly, but must instead look for the signs of love in a caress, a word, a sacrifice.

And so it is with the glory of God. You cannot see it directly. It is not, I think, that it is too bright and that we must look way as from the blazing sun. Although that may also be true. Nor, I think, is it that it is a kind of mathematical limit or Platonic form which exists but not in this place. Although, there may be something to that analogy as well.

I have no theory about why we must interact with the things that matter most in our life but–as a Mormon–I sense a deep connection to the question of embodiment. We believe that this physical existence is not a necessary evil but a progressive step in our grace-fueled upwards trajectory. Something about physicality, about the specificity of mortal experience, allows the abstract to be instantiated and therefore experienced.

One message of the story of Lazarus is that the glory of God is not separate from our mortal experience, but exists within it. The physical and tangible reality of Lazarus risen–shadowy presage of Christ’s greater triumph–is not incidental.

What does this have to do with Calvin and his tiger? Simply this: art–with the specificity of character and plot and setting–is another way we can approach the abstract, the profound, and the divine. There is something about the specificity of Calvin as this particular boy and Hobbes as this particular tiger that bring us closer by circles to great truths than straight lines ever could.[ref]Also, they are very funny and I love them no matter what. Just to be clear. [/ref]

They are very funny and I do love them no matter what.

Thanks for the link.

Personally I see glory as achievement, merit, earned status. So of course its invisible.

http://www.jrganymede.com/2012/10/31/earned-respect-unconditional-love/

http://www.jrganymede.com/2014/03/11/satans-plan-and-gods-silence/

But there are tantalizing hints in the scriptures that some day we may actually be able to see it directly. The idea of metaphysical concepts like glory and love being perceivable in the hereafter moves me deeply.

There are two fictional worlds that I probably over-rate because of that. One is Wright’s Orphans of Chaos series, where the heroine can directly perceive the moral nature of things. The other is The Nightlands, where spirituality can be measured by sensitive instruments.

What would we think of a person who communicated only indirectly? Maybe this person is extremely smart and capable, but speaks and acts only through others or in oblique riddles. We’ve all probably had teachers like this, who are infuriating in the moment but their wisdom can be seen in hindsight.

If you’re lucky, the people like that in your life are also smart enough to know direct action is sometimes best. If I show up at their office in anaphylactic shock, they won’t ponder the epi-pen in their hands and muse poems about bees; they’ll stick me with it to save my life.

http://wp.patheos.com/blogs/unreasonablefaith/files/2008/12/calvin-565×191.png

God gets a pass on the direct-action puzzle if you assume this life is a practice round. I don’t have that sort of faith. I don’t know anyone who thinks of death with the same benign “oopsy!” we might give a Super Mario slip-up. That’s rational, that even the most faithful can recognize it’s the biggest possible gamble.

http://cdn2.sbnation.com/imported_assets/1025851/bill4.gif

When presented with an action or statement attributed to God, I like to ask myself what we would think of a person, someone we all thought of as extremely smart, kind, and wise, who did the same thing. Would we still think that person was smart, kind, or wise?

It sounds like you’re sort of scrapping for a fight on this one, Ryan. Forgive me if I’m reading too much into the tone.

But the questions you raise–complete with Calvin and Hobbes comics!!–are ones that I respect. I’ve never said that atheism or agnosticism are not reasonable positions to hold for the simple reason that I do not think they are unreasonable positions to hold.

Now, the New Atheists in particular irritate me to no end. But that’s just a recent fad. Atheism / agnosticism is a perfectly legitimate response to the Problem of Evil or, as you mentioned here, the simple question of why–if God cares about us at all–He is so absent.

I think the questions have answers, somewhat, that go beyond this life being a practice round or death being a triviality (I can’t pretend to look at my own impending demise with perfect equanimity). I am a religious person, and I do believe in God. But I don’t think it’s obvious or self-evident or have any bone to pick with those who see things differently just because they see things differently.

In other words: you won’t get a fight from me over this particular issue.

A fight wasn’t my intent. My interest in internet arguments is long gone. Discussion that improves my understanding, and teaches others, now that’s interesting.

I just wanted to throw out some reasonable questions, like Calvin asked about Santa, for discussion. A similar question for someone with my beliefs might be “If entropy is unavoidable and heat death of the universe is inevitable, why do you do, or care about, anything at all?” (Habit, is my answer, until I think of something better. Also love, and tacos, etc.) It’s easy to see such a pointed question as confrontational, but that wasn’t my intent.

I think it’s useful for even the most religious to think about what God says and does objectively, the way we might an economic policy. If God tells us to give to the poor, is it sustainably helpful to just dump money, or does more good come of it if we subsidize education and basic food/housing, etc? Thinking of God’s statements and actions as if they’d been done/said by a person is a good tool toward that end. Because it’s hard to think objectively about God, just change up the name. Blind taste test.

Ryan-

Well, in the interests of discussion, here is my current thinking on some of these tough questions. For me, it mostly comes down to two things.

First, the idea that life is intentionally difficult. That’s actually the origin for the name of this blog. This isn’t so much about life as an inconsequential “practice round,” but it is about the idea that the purpose of our life is to change, become, and grow. And these are things that–generally speaking–are not comfortable.

Second, I rely a lot on the metaphor of parent / children. I think, as adults, we tend to discount some of the visceral depths of fear and pain that children go through more or less as a matter of routine. Because we can’t really remember ourselves. Because we have the perspective that makes their experiences seem mundane. As a result, a lot of what terrifies or horrifies children is kind of hilarious to adults. One quick example: I was at home with the kids one day when I heard that piercing shriek of sincere pain / fear that will instantly set any parents’ heart racing. I sprinted upstairs to where my child (I honestly don’t remember which one) had been taking a nap and found him–still wailing traumatically–curled in the blankets in the corner of the room. I did a check for any visual signs of injury and there were none, then set about trying to figure out what was going on. The result? The sound of the garbage truck picking up trash cans outside had terrified her out of her mind.

As I said: this is funny as an adult. But there was nothing funny about her fear. Similarly, my son often woke up in the middle of the night when the emergency lifeflight copter flew low over our house, absolutely paralyzed with fear. Or, to be less humorous, there’s the rather disturbing but altogether mundane reality of having to hold a writhing child firmly in place so that he or she can get a vaccination.

To us these are either sad or just one of those things you have to get through. But to a child? The terror and fear are genuine, and equally as valid–subjectively–as our own fears and pains.

So I imagine that it is possible that from God’s perspective a lot of what terrifies us–including death–is not objectively worthy of the fear we hold for it.

Keep in mind, none of this gets to why I believe. I’m just talking about the way I address the problems my belief presents to me. If God is such a powerful, nice guy why do things suck and why is He so hard to get a hold of? My answer, at this point, is that things suck partly because growth sucks (and this is also why we have to be largely alone) and and also partly because our perspective makes them seem worse than they are.

These aren’t perfect answers. Just what I’ve got so far.

And also tacos. And love.