I just read David Brooks’ most recent column: The Next Culture War. In a nutshell, he argues that Christians ought to abandon their decades-long, fighting retreat against the sexual revolution. “Consider putting aside,” he writes, “the culture war oriented around the sexual revolution.” Channeling Disney’s Frozen, he argues that Christians should just let it go. After all, aren’t there enough other problems to tackle? “We live in a society plagued by formlessness and radical flux, in which bonds, social structures and commitments are strained and frayed,” he writes.

I have a lot of respect for David Brooks. He’s one the people I’d most love to have a lunch conversation with.[ref]Others, if you’re curious, include John McWhorter, Megan McArdle, and Jonathan Haidt.[/ref] But, he doesn’t seem to understand that his suggestion asks for Christians to bail the water out of a sinking boat while ignoring the hole in the hull.

You see, the sexual revolution is the reason that we live in a society that is “plagued by formlessness and radical flux.” In The Social Animal, Brooks argues against the atomization of society on both the left and on the right, with each side focusing myopically on divisible, separable, self-contained individualism. The left argues that human individuals can construct their own gender and sexual identities free from repercussions and it therefore sees free birth control and elective abortion as fundamental rights. The right views collectivism with a hostile gaze, channeling Ayn Rand at times, and argues for personal responsibility sometimes to the point of callousness. These are twin heads of the same coin, and Brooks is right to focus on it. It is one of the defining philosophical tragedies of our age.

But what he seems to fail to grasp is that this radically individualized view of human nature follows in part directly from the sexual revolution. To the extent that the sexual revolution has been about excising sex from the context of marriage and family, it has been an assault on the biological family unit. And this unit–including the bond of husband and wife to each other and also to their children–comprises the two most essential bonds in human society.

To put it simply, social conservatism is animated in no small part by the conviction that biological families are irreplaceable. And so, to the extent that Brooks’ invitation is for social conservatives to give up and try to replace them, he is asking something of us that we simply cannot provide.

As a brief caveat, it’s not entirely clear that that is what he’s asking. He writes that we ought to “help nurture stable families.” I’m just not sure how he imagines this should be accomplished in practice. At one point, he suggests that conservatives abandon the culture wars while at another point he says that “I don’t expect social conservatives to change their positions on sex.” Which is it? Because conservative positions on sex are their participation in the culture wars. It may be the he merely thinks we should keep those beliefs quiet, but again: how does one practically “help nurture stable families” while abandoning resistance to the sexual revolution? Subjective sexual morality, open relationships, sex before marriage, pornography: these are not incidental things that happen to exist alongside “formlessness and radical flux.” These are the acids in which the stable family–as a normative and aspirational social beacon–dissolves.

And this cuts both ways, by the way. To the extent that social conservatives are unwilling to abandon their commitments, their opponents are equally unlikely to let the issue go. Thus, I have to express a deep skepticism of the upside of Brooks’ plan. His idea is that–if we assume for a moment that it is possible to meaningfully nurture families without participating in the culture wars–that suddenly religion will be well-thought of in the world. All of a sudden, we would be known as “the people who converse with us about the transcendent in everyday life.”

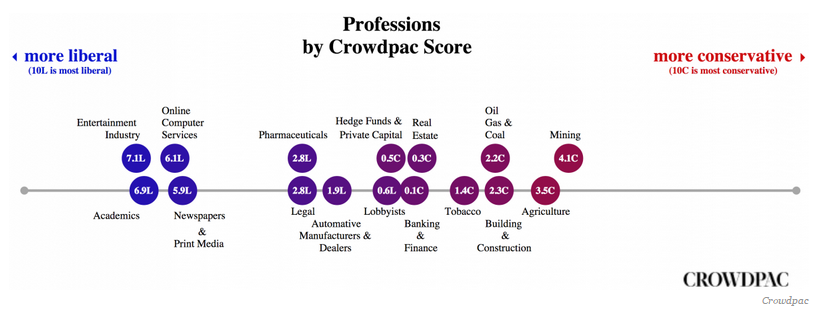

This is impossible, because the commitment social conservatives have to their values is mirrored by the commitment social liberals have to their mutually contradictory values. And as long as social liberals dominate the opinion-making sectors of our society their animosity will continue to be expressed in part by ongoing negative characterization of social conservatives as backwards bigots. And, make no mistake, social liberals do dominate the opinion making sectors of our society: academia, the press, the entertainment industry, and the Internet. Even if social conservatives did go quiet on their beliefs, I have very, very little confidence that our image would suddenly be rehabilitated.

Here is the reality: social conservatives are fighting the sexual revolution–despite it being a losing proposition thus far–because we believe that nothing does more good for children than being raised by their biological parents and that very little does more harm than for little children to be deprived of this natural right.[ref]The extreme cases where one or both of the parents is abusive or neglectful are those exceptional cases.[/ref] This belief necessitates viewing sex as more than merely a recreational activity or even a question of strictly intrapersonal, subjective meaning to be negotiated between the willing adult participants. The belief that immature human beings have a strong moral claim on their parents for protection logically requires a view of sex as a deeply significant act for which consenting adults–male and female together–ought to be morally, socially, and legally responsible.

There is certainly room for compromise and innovation within this conflict. The idea that social conservatives want to wholesale turn back the clock to an imaginary 1950s is an unfair stereotype. Much of the progress–both for women and for minorities–since the 1950s comes to us as precious treasure, dearly purchased and should be treated with humility, gratitude, and respect. Many of the contentious technologies that have fueled this debate–from the pill to IVF–are morally neutral technologies which can certainly coexist with a thoughtful, robust view of normative sexual ethics. There is room for these views to be better articulated within social conservatism, and for some social conservatives to take them more seriously and moderate their positions.

And so I do not want to meet Brooks’ call with a hardline refusal. It’s worth considering. What I wish to convey is that social conservatism is restricted in its freedom to adapt. That is not a design flaw. The point of having principles at all is that–while they may be interpreted or applied in innovative or flexible ways–there is a limit to that flexibility. There are some things that a person cannot do without abandoning principle. For social conservatives, the central principle is the care and protection of society’s most vulnerable, which means our children (before and after birth). An additional article of faith is that no institution can replace the biological family in filling that role. As a result, social conservatives not only will not abandon their opposition to the sexual revolution, they cannot do so and remain social conservatives. Can we do more without abandoning that opposition? I’m sure we can, and I hope we never stop being motivated by that question.

Excellent response. Loved the part about the 1950s, such an unfair characterization. Not all change is progress.

You seem to be trying to explain something which has gone under-explained to the left, which I really appreciate. Here’s a bit which seems to encapsulate what I see as inadequately conveyed (as evidenced by the “How does gay marriage affect your marriage?” question):

“Subjective sexual morality, open relationships, sex before marriage, pornography: these are not incidental things that happen to exist alongside “stable families.” These are the acids in which the stable family–as a normative and aspirational social beacon–dissolves.”

As a left-of-center individual, I understand that you believe this, but I don’t understand why. Why cannot a subset of the population establish a norm for itself which other subsets don’t follow? If everyone is free to adopt whatever sexual morality does no harm to others, why should we expect that no one will aspire to follow those moral precepts which are conducive to stable families?

One of my deepest discomforts with the political left is the appeal of authoritarian intervention to force others to behave in ways we regard as beneficial for all. I love government-run recycling programs which make it easy to recycle and help people develop positive habits, but am not at all happy with those which involve looking through people’s trash to punish those who fail to recycle, for example. I like the idea of holding myself and my family to a certain standard, but not expecting others to follow that standard nor holding myself responsible (largely through my support of government) for anything but intervention to prevent significant violations of rights. I want to create a culture of reading within my family, but if my neighbor doesn’t, that’s not on me. I think it would make life measurably worse over the long term for those children, but I don’t have to abandon my commitment to reading in my family to let them do things that way.

Why isn’t the sexual revolution the same way? Why can’t you live a life opposed to sin and build a strong family while others sin and weaken their families? I understand that this ought to seem to you like a tragedy, just as neighbors who don’t read to their children would to me, but that seems to me like an unavoidable cost of freedom. One highly speculative option: perhaps social conservatives think that people are only (or much more probably) able to take responsibility fully when they’ve had a stable family–on this view, maximizing freedom would entail limiting some freedoms, like those implicated in the sexual revolution, in order to head off their freedom-destroying consequences. But I’ve no idea whether something like that is at work, and even the concession that it can improve overall freedom to limit some freedoms has been anathema to some libertarians of my acquaintance, so that seems like a particularly potentially weak part of that speculative gesture at an answer.

Kelsey-

The simplest answer is that that’s not how human nature works. Human beings are incredibly sensitive to social norms. A couple of recent examples (that have nothing to do with the sexual revolution) underscore that is.

First, there was an attempt by the UK government to get citizens to pay their taxes on time. Of all the policies they tried, the one that worked the best was incredibly simple: they told people that 9 out of 10 paid their taxes on time. As a result of adding this single sentence to the mail that went out, they got compliance to go up by 30%. That’s huge.

A similar study was done in California. Researchers wanted to get people to use less electricity. They left doorhangers on their doors. Some appealed to budget (use electricity during the day to lower your bill) and others to environmentalism (cut carbon emissions by lowering electricity use during the day), etc. They all had exactly 0 long term effect. But then they tried a different message, that said “You use more energy than 80% of your neighbors, try lowering your consumption.” (Or whatever the number was.) Again: people who got this doorhanger lowered their electricity consumption by 6%, and it was a sustained drop.

Think about the huge impacts a single, one-sentence comparison can have. Now try to imagine the cumulative effects of a lifetime of exposure to social norms, especially to children. It goes right back to John Donne: no man is an island.

So, the first part is addressed above. You can just mind your own family, but its very, very difficult. But I just wanted to point out that this isn’t really a question of freedom, primarily. I don’t support any attempt to use the power of the state to force people to behave morally (as I see it). I think that’s a terrible idea.

But just because I don’t want to mandate that the state install cameras to force parents to read to their children (for example), doesn’t mean that I can’t argue that parents should, in fact, actually read to their children. Or that I should just shrug when I see the prevailing moral consensus that reading is important start to fade away.

There’s more to society than just isolated individuals with no power on the one hand, and the full force of the state on the other. Social conservatives tend to emphasize this in-between realm, populated by family, extended family, civic organizations, churches, neighborhoods, etc.

This is very much at play as well, which is why social conservatives tend to be so concerned with children. As an adult, you can make up your own mind to break the taboos you were raised with, have sex outside of marriage, whatever. But every child deserves to have a stable upbringing so that–when they get to that point–they are making the decision in a truly free way.

But I do think this is secondary to the incredible power of social norms, which is the primary concern of social conservatives. (With good reason.)

I think you’re right that this is an important difference between American conservatives and liberals. My perception, and I’d be interested to know whether it is yours, is that liberals tend not to say as much about the in-between institutions, and don’t get terribly exercised about them. So the natural reaction, I should think, would be for the full force of the government to be employed rarely or never to force people to live in a way which inculcates conservative values, but for conservatives instead to focus their efforts on the in-between realm, which liberals seem unlikely to oppose with anything like the energy or effectiveness they bring to bear against conservative legal moves. I should think a country with largely conservative values with a legal system which protects the rights of minorities would please virtually everyone. If there are no barriers to women participating in the workforce, and they are hired and promoted based on their merits rather than with the assumption that they will be less committed to their careers than their male counterparts, only the most extreme feminists would object should many of them choose not to take paid employment. If those who experience same-sex attraction or gender dysphoria may choose to pursue lives which indulge those attractions or explore alternative gender options without legal or violent extralegal repercussions, but don’t because it would be inconsistent with their own values, who would mind? If the government stops declaring the existence of a single God, but private individuals are almost universally devout, what would be illiberal about this?

My expectation is that the real problem is that large majorities are very rarely good about not defending their values with law and policy. So liberals tend to see situations in which, for example, very few women go into Physics as a sign of such entrenched bias and privilege, rather than a meritocracy which fairly deals with everyone interested in Physics, most of whom are men. I wonder whether it’s reasonable to hope that conservatives could get most of what they want culturally while also really understanding the position of privilege that leads to, and how to mitigate it. My impression is that liberals don’t have a great answer for this–rather, when they become culturally dominant, they use exactly the same tactics the Establishment/The Man/the patriarchy/whatever abused for centuries. But I can’t help thinking that, if we could avoid bullying others into choosing as we’d like them to, the Culture Wars would be sort of unnecessary.

Kelsey-

So, I have two main responses. First, I think you’re absolutely right that the majority is always tempted to enforce preferences with the full power of state. However, I think it is true that liberals are more prone to this tendency towards totalitarianism than conservatives precisely because conservatives view society as a spectrum populated by individuals, layer upon layer of various voluntary organizations, and then finally government whereas liberals tend to see just two things: individuals and government. So conservatives have other channels for their reforming and meddling inclinations, but liberals do not.

Second, I think you underestimate the difficulty of a kind of neutral government. Or at least, again, that’s something that conservatives are better at. I know it sounds like I’m just indulging in petty partisanship, but it’s important to clarify that these beliefs (that conservatives are less inclined to meddle via government and better at pluralism) are the reason I stay conservative.

In particular, the conservative view of government is primarily as the gaurantor of negative liberties where liberals see government as the provider of positive liberties. From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

So conservatives belief in a right to life: no one is allowed to murder you. Liberals believe in a right to healthcare: someone has to actually provide money and services for your health needs.

I think it’s clear to see that liberal policies to provide positive liberties are much, much more threatening to the kind of “live and let live” pluralism that you are talking about.

In practice, think of something like welfare. There is no way to separate welfare policy from impacts on family structure. There are many credible scholars who believe that it is welfare policies which have substantially devastated the black family. Slavery often gets the rap, and this makes intuitive sense. Slavery was horrific, and nothing breaks up a family more literally than separating mother and father and children and selling them to different owners. However, no matter how horrible slavery was or how intuitive that explanation may be, the fact is that black families were substantially stronger in the first half of the 20th century than in the second half, and therefore slavery cannot explain the collapse of the black family. Nor can Jim Crow. That absolutely does not defend either practice one iota, but it suggest just how profoundly attempts to provide positive liberties (like housing, for example) can impact the realm of family and church and community that conservatives are trying to defend. (Further reading to back up this stuff about slavery and families here.)

In short: I like the idea of a pluralistic, minimalist government and a kind of live-and-let-live society. Conservatives were very bad at it, historically, but I strongly suspect liberals will be even worse.

That analysis makes a lot of sense to from a historical perspective, but I think it neglects some recent and very promising changes which pull apart the degree of government intervention with its goals. You describe positive liberty as something liberals have historically sought to have government provide with massive, direct programs, and I think that’s right, but there are also much less intrusive ways of promoting the same goal. I’m thinking about the “libertarian paternalism” of Nudge.

Say you want people to be healthy, which everyone wants for themselves. You could have a program of forcing people to eat right and exercise, but that would be exactly the sort of government overreach which gives even liberals fits. Instead, you can have government-run cafeterias offer all the same foods they always have, but with the healthier options placed in more salient locations. This has a significant effect–people develop healthier eating habits when you do stuff like this, and they are more able to accomplish a wider variety of goals because of their increased health. But you’ve pursued that positive liberty goal with a pretty light touch. The book uses similar examples for lots of other cases.

That’s the sort of place I see hope, because I know of no reason for liberals to be attached to the highly intrusive means they’ve tended to default to in the past. If the objection of conservatives to positive liberty as a goal has been the awful and sometimes counterproductive means of pursuing it, perhaps we can agree that, pursued differently, positive liberty as a goal has much to recommend it. Liberals tend to want to force people to bake cakes for gay weddings, for example, but if we instead put the burden of finding an alternative baker on the provider rather than the couple (and only if no reasonable alternative could be found force such baking), liberals’ principle goal of keeping gays from being frozen out of the marketplace could be achieved with less intervention.

Incidentally, I’m not sure the decline of the black family is a great example of a reason to see conservatives as guarantors of negative liberty while liberal providers of positive liberty were ruining things. My impression is that racist mandatory minimum sentences pursued by conservatives in the war on drugs have been awful for black families, and it’s hard to see them as either unintrusive nor connected to negative liberties. But that doesn’t refute your primary point that the liberal provider model has unintended consequences, which I happily concede.