So here is an interesting article I have come across: star wars ring theory.

“Ring theory” definitely sounds cool. It’s got a vibe that says cutting-edge and sophisticated, probably because it’s just a couple of letters away from “string theory.” And the site itself has no shortage of grandiose rhetoric, describing why the Star Wars prequels are not so bad after all because really George Lucas was using an “ancient technique” that allowed him “to reach a level of storytelling sophistication in his six-part saga that is unprecedented in cinema history.”

I’m pretty sure they’re serious.

Now, this isn’t the first defense of the prequels I’ve seen recently. You can basically assume that whenever society seems to be headed one way, a couple of intrepid bloggers are going to try to make a name for themselves by going the exact opposite direction out of sheer contrariness. As a curmudgeon myself, I can appreciate that.

That doesn’t mean they actually have a point, however.

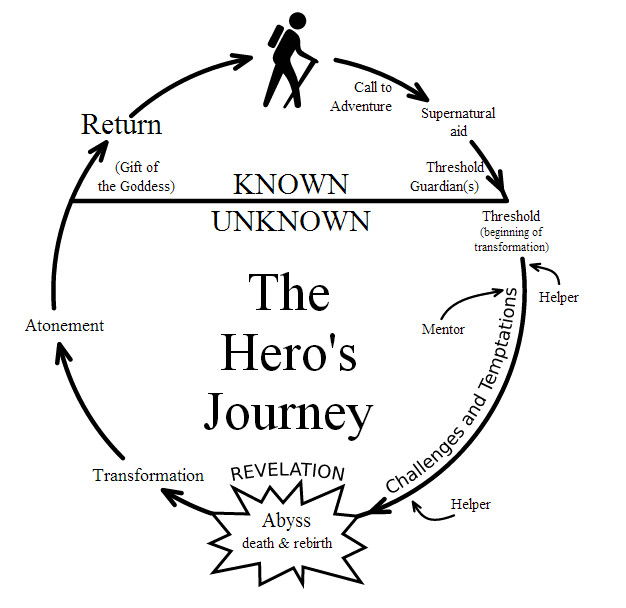

Now, this article was pretty disappointing from a standpoint of “storytelling sophistication.” In fact, I can’t think of anything less sophisticated than the actual theory which they kind-of, sort-of explained. It boils down to: the prequels and the sequels recapitulate a lot of the same elements. Which is not actually surprising at all if you understand the idea of the hero’s journey[ref]AKA the “monomyth” if you want to sound impressive.[/ref] The whole point of the theory is that there’s one archetypal adventure, and all our stories are echoes of the Platonic ideal of adventure[ref]I’m mixing philosophical metaphors here, I know.[/ref] Now, if there’s any validity to that notion at all, and in particular if George Lucas was a devotee of that theory (which he was) then isn’t it rather obvious that his stories–which are designed to be expressions of a particular template–are going to have a lot of similarities?[ref]Just check out this list from IMDB of 66 different movies that play out the monomyth. If you can find parallels between Pride and Prejudice and Guardians of the Galaxy, I don’t think you’re going to have a hard time finding parallels between Star Wars and, uh… more Star Wars[/ref]

But let’s assume for a moment that George Lucas really was being super-sophisticated. Is that actually a really good defense of the prequels? I don’t think so.

When I was an undergrad we had a pair of required courses called the core courses: sort of a combination of a literary survey with some philosophy and intellectual history. (Works I can remember reading: The Gospel of Mathew, Things Fall Apart, and On the Origin of Species.)[ref]I think the idea of these classes is fantastic, btw.[/ref] Well, somewhere along the line we were also required to attend a concert on campus. If I recall, the title of the contemporary (modern? post-modern?) symphony was “Frankenstein” or something very similar. The music was pretty awful (which goes without saying), and the presentation was quite odd: the casually-dressed orchestra alternated playing instruments with whirling various toy music-makers over their heads and there were also lots of snippets from popular culture like Mighty Mouse or the old Batman TV show that played at various parts as well.[ref]The whole thing was a bit of a disaster. The students were incredibly rude and talked and joked through the entire performance. But it’s not hard to see why: an orchestra in jeans and t-shirts is subconsciously projecting an image that says “rehearsal” instead of “performance.”[/ref]

In class the next day, the professor pushed us pretty hard to try and understand the piece. I quoted Robert Heinlein at him and called the work “pseudo-intellectual masturbation.” The quote comes from a scene in Stranger in a Strange Land:

“Jubal shrugged. “Abstract design is all right-for wall paper or linoleum. But art is the process of evoking pity and terror, which is not abstract at all but very human. What the self-styled modern artists are doing is a sort of unemotional pseudo-intellectual masturbation. . . whereas creative art is more like intercourse, in which the artist must seduce- render emotional-his audience, each time. These ladies who won’t deign to do that- and perhaps can’t- of course lost the public. If they hadn’t lobbied for endless subsidies, they would have starved or been forced to go to work long ago. Because the ordinary bloke will not voluntarily pay for ‘art’ that leaves him unmoved- if he does pay for it, the money has to be conned out of him, by taxes or such.”

“You know, Jubal, I’ve always wondered why i didn’t give a hoot for paintings or statues- but I thought it was something missing in me, like color blindness.”

“Mmm, one does have to learn to look at art, just as you must know French to read a story printed in French. But in general terms it’s up to the artist to use language that can be understood, not hide it in some private code like Pepys and his diary. Most of these jokers don’t even want to use language you and I know or can learn. . . they would rather sneer at us and be smug, because we ‘fail’ to see what they are driving at. If indeed they are driving at anything- obscurity is usually the refuge of incompetence.”

After a while, however, a light began to dawn on me. Frankenstein’s monster is created from patched-together body parts. The monster is large because Dr. Frankenstein had to use body parts from large human beings in order to be able to more readily work on them. So you have s shambling imitation of a human being created out of a patchwork of larger-than-life bits and pieces. Well, that’s exactly what the symphony was: the pop-culture snippets were all related to superheroes of one kind or another, and so you had this musical patchwork of larger-than-life pop-culture snipped together into a monstrous mockery of music.

The professor sat back in his chair with a smug look when I shared this insight. “Now what do you think of the piece?” he asked.

I told him I still thought it was pretentious drivel. Every word of Jubal’s / Heinlein’s critique applies just as well after you crack the code and get the secret message as before. Clever is nice, but it isn’t a substitute for good.

I’m not saying there’s no room for cleverness or subtlety. I like cleverness and subtlety. One of my biggest complaints about most TV shows is that they over explain everything to be sure even the dimmest audience member splitting their attention between the show and Twitter won’t miss any important bits. But that doesn’t mean that just because you make your movie / book / TV show / symphony an enigma wrapped in a mystery concealing a riddle that it’s going to be any good.

Ring theory isn’t impressive. Even if it was, it wouldn’t make the Star Wars prequels any good.

The best art seduces you with enough of the right ‘language’ so you can see the subtlety and cleverness of what they’ve done before losing interest. Not easy to do, and not very many can do it well. When they do, the result is quite magical.

No way am I going to defend the prequels. I do want to underline the point that distinguishing good vs clever is real work and can’t (shouldn’t) begin and end with “I don’t get it.” Case in point for me is post-modern art. Judging from photographs alone, I pretty much don’t get it. But I walked into several rooms full of the real thing one day and was entranced. I would pay to return. (Kind of an easy example, since this was at the Hirshhorn Museum and the first room was works by Mark Rothko and the next had a Jackson Pollock on the floor.)