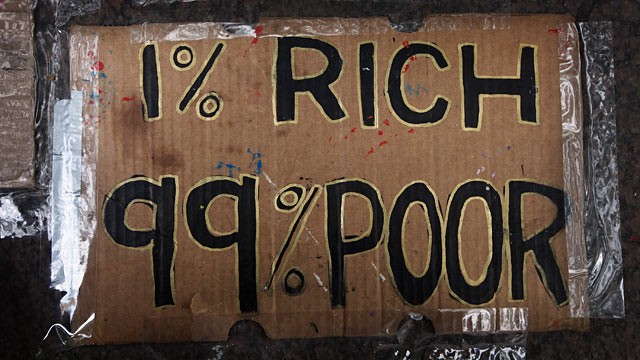

A new report by the Manhattan Institute’s Scott Winship looks at the claims regarding “the rich getting richer” and the top 1% making most of the gains since the Great Recession. Winship’s main findings include:

A new report by the Manhattan Institute’s Scott Winship looks at the claims regarding “the rich getting richer” and the top 1% making most of the gains since the Great Recession. Winship’s main findings include:

- An accurate accounting of who is gaining and losing in the U.S. economy requires a broad view across an entire business cycle: while the richest households tend to gain the most during economic expansions, this is partly because they also lose the most during recessions.

- In the current, ongoing, business cycle, real incomes declined between 2007 and 2014; the top 1 percent experienced nearly half of that total decline.

- From 1979 to 2007, 38 percent of income growth went to the bottom 90 percent of households, amounting to a 35 percent increase ($17,000) in its average income.

Check it out. An excerpt can be found here.

Perhaps greater familiarity with economics would leave me more impressed, but on a superficial, layman’s reading, that’s a frighteningly bad piece. In rebutting the claim that the top 1% have captured virtually all of the gains of the post-recession expansion, Winship writes, “This means that the top 1 percent saw their incomes rise by 29 percent ($280,000), on average, and the bottom 90 percent saw a rise of 3 percent ($900).” This seems like an admission that the claim he’s rebutting is absolutely true, but he claims without offering reasons that this result is cherry-picked; it’s more accurate to consider the entire business cycle.

Of course, we don’t know when the current expansion will end, so it’s unclear whether he’s even capturing the full business cycle when he chooses to start his preferred window in 2000, but suppose he is. He makes the claim that, “Even more stunning, the top 1 percent’s income was essentially no higher in 2014 than in 2000—a fact that provides context to the income stagnation experienced by the U.S. middle class since 2000.5” This is an astonishingly stupid claim in light of the actual content of footnote 5, which states that the data he’s using ends in 2011! So, yes, when you ignore five years of growth, growth does look smaller.

Perhaps even worse is a cunning bit of mathematical misdirection. Suppose it’s true that top 1% income is highly volatile, dropping more in recessions and rising more in expansions. Winship never seems to get around to acknowledging that expansions are several times longer than recessions, on average, which radically tilts the balance of those effects in favor of the very wealthy.

Is there some reason this isn’t as disappointing as it seems?

“This seems like an admission that the claim he’s rebutting is absolutely true…”

Except that he bumped the claim from 91% of the income gains to 54 percent. Almost all =/= half. One can think that is still too high, but that is a drastic difference. And this is *before* he even takes into consideration the income losses of the top 1 percent during the recession.

“This is an astonishingly stupid claim in light of the actual content of footnote 5…”

I’m actually not clear on this one myself. When I first read it, I thought he was drawing on the Piketty-Saez data for his 2014 numbers. If you look in footnote 4, he’s crunching their data using the PCE deflator. This seems to be the data he is relying on between footnote 4 and 5.

In footnote 5, he says, “The data, *below*, from the Congressional Budget Office, which extends only through 2011…” *Below* appears to refer to the analysis of past business cycles in the next section. In other words, footnote 5 may not have anything to do with the 2014 numbers. However, he does start to pick at Piketty-Saez’s data for “indicat[ing] that faster growth at the top also probably put the top 1 percent’s income higher in 2014 than in 2000. The CBO data are superior to the Piketty-Saez data for a number of reasons, including their inclusion of more income sources in their definition of household income (see n. 7 below) and their use of household, rather than tax, units.” So, it looks like both parties are making estimates about the 2014 gains of the top 1 percent using different sets of data.

I emailed Winship for clarification. I’ll let you know if I hear back.

Winship was kind enough to reply:

“In rebutting the claim that the top 1% have captured virtually all of the gains of the post-recession expansion, Winship writes, “This means that the top 1 percent saw their incomes rise by 29 percent ($280,000), on average, and the bottom 90 percent saw a rise of 3 percent ($900).” This seems like an admission that the claim he’s rebutting is absolutely true, but he claims without offering reasons that this result is cherry-picked; it’s more accurate to consider the entire business cycle.”

I never say that the claim that all gains have gone to the top DURING THE RECOVERY is wrong.

“Of course, we don’t know when the current expansion will end, so it’s unclear whether he’s even capturing the full business cycle when he chooses to start his preferred window in 2000, but suppose he is. He makes the claim that, “Even more stunning, the top 1 percent’s income was essentially no higher in 2014 than in 2000—a fact that provides context to the income stagnation experienced by the U.S. middle class since 2000.5” This is an astonishingly stupid claim in light of the actual content of footnote 5, which states that the data he’s using ends in 2011! So, yes, when you ignore five years of growth, growth does look smaller.”

In the previous expansions, the share of gains going to the top declines as the expansion progresses. And yes, 2000 is a business cycle peak. I’m actually using data through 2014, not through 2011. The CBO data goes through 2011, the Piketty-Saez data through 2014. I use both to estimate the 2000-14 change.

“Perhaps even worse is a cunning bit of mathematical misdirection. Suppose it’s true that top 1% income is highly volatile, dropping more in recessions and rising more in expansions. Winship never seems to get around to acknowledging that expansions are several times longer than recessions, on average, which radically tilts the balance of those effects in favor of the very wealthy.”

Irrelevant. The point is that the disproportionality of the gains of the (longer) expansions are matched by the disproportionality of the losses. I never claim that inequality isn’t rising—it is. I’m just saying that you need to account for both the gains in expansions AND the losses in recessions. If that means, on net, the top still sees outsized gains—and they do—so be it. He’s saying I’m trying to hide a conclusion that isn’t the subject of the brief.