I just finished listening to a bunch of science fiction stories in rapid succession so that I could cast informed votes for the annual Hugo awards and post the reviews to my new blog.[ref]The Loose Canon is where I will do most of my future blogging about science fiction.[/ref] That done, I returned to some of the non-fiction audiobooks I’ve been waiting to get into, especially Redefining Reality: The Intellectual Implications of Modern Science. It’s been a fantastic spring day, and there was an exquisite, gentle evening breeze as I walked the dog. Meanwhile, Professor Steven Gimbel explained the impact of World War II on the field of social psychology:

In the first half of the 20th century, psychology had the luxury of debating whether a subconscious mind existed and whether scientific methodology required limiting the field of study to stimulus and response, but after the horrors of World War II, psychology changed… The specter of the Holocaust raised deep and troubling question about the human mind and its relation to authority… The reaction to Nazi atrocities in the scientific world is shaped by what are perhaps the three most famous psychological experiments: Stanley Milgram’s obedience study, Solomon Asch’s group think study, and Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford prison study. [ref]The quote is my own transcription, and I added the hyperlinks.[/ref]

I think Millgram’s and Zimbardo’s experiments are the most famous. At least, those are the ones that I’ve read about and seen the most. I was familiar with Asch’s study as well, but I haven’t seen it come up as often, and I was unprepared for how deeply a simple remark made by Gimbel would strike me. It hit so forcefully that I hit pause on the audiobook (to keep that thought forefront on my mind), came home, opened my laptop, and began this blog post.

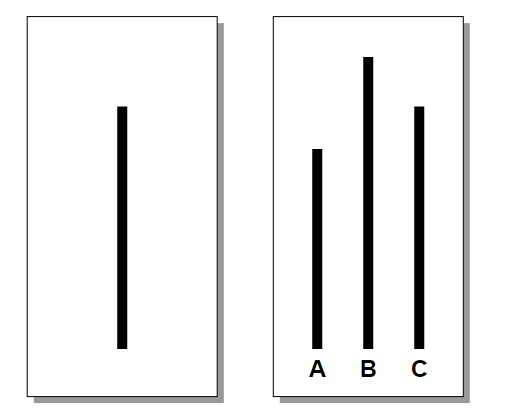

In Asch’s study, participants were given a simple task. They had a reference image that showed a vertical line, and then another image that showed three vertical lines. One of the three matched the vertical line in the reference image, and all they had to do was pick out the correct match. They were asked to do this 18 times. The trick is that the participants were seated at a table with seven other people who were secretly in on the experiment. On the first two rounds, these seven individuals all gave the same answer, and it was the correct one. But on the third trial, these individuals all gave the same incorrect answer. Over the course of the next 15 trials, the seven plants gave the wrong answer 11 times, and in each case all seven of them gave the same incorrect answer.

So you’ve got eight people seated around a table answering a perfectly obvious question. Seven of them have just given the identical, incorrect answer. The point of the experiment was to find out what the eighth person–the only real subject of the study–would do. Given that this is considered one of the “three most famous psychological experiments” you can guess how it turned out even if you don’t already know: 75% of subjects went with the group consensus (even though it was obviously wrong) at least one out of the 12 times when the seven fake participants picked the wrong answer.

There are all kinds of interesting details to the study, especially when it comes to the rationales that the participants gave afterwards to explain why they had refused to go along with the group or why they had, at least some of the time, opted to go along with the group despite what was clearly true. But here’s what Gimbel said about the study that so arrested me:

Asch expanded the study to see what would happen. He showed that the bigger the majority, the stronger the pull to conform, but that if even one person dissented before the test subject, that the test subject was then more likely to voice his different view. Asch showed empirically that having someone else agree with you is a powerful tool in making people willing to take a contrary position. But, if that person [the test subject] were deserted by his fellow dissenter, conformity followed rapidly.[ref]I transcribed this quote from the audio and then added emphasis to the text version.[/ref]

Now, before I continue, I want to take a moment to explain that–contrary to popular opinion–I’m not interested in attacking conformity. Conformity gets a bad rap in movies like Dead Poet Society.

The sentiment in that clip is hogswash. Unfortunately, so is most anti-non-conformity sentiment. There’s an entire guide to being a non-conformist, but–like all such ironic anti-non-conformity statements–the actual point is that non-conformity is bad because it’s a kind of conformity.

So, even the anti-non-conformists are trapped in an non-conformity mindset. Conformity can’t catch a break. Which is a shame, because conformity is actually pretty important in helping to form human society and–because we are social animals–to form who we are as well.

In The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt introduces this concept in a chapter called “The Hive Switch.” He starts with an example of exactly the kind of military drill (e.g. marching) that Dead Poet Society maligns, citing Wiliam McNeill (a World War II veteran) describing drill this way:

Words are inadequate to describe the emotion aroused by the prolonged movement in unison that drilling involved. A sense of pervasive well-being is what I recall; more specifically, a strange sense of personal enlargement; a sort of swelling out, becoming bigger than life, thanks to participation in collective ritual.[ref]The Righteous Mind, page 221[/ref]

After his service, McNeill studied this kind of conformity (which he called “muscular bonding”) and found that it “enabled people to forget themselves, trust each other, function as a unit.”[ref]The Righteous Mind, page 222[/ref] What works like Dead Poet Society miss[ref]And it is far from alone in this regard.[/ref] is that conformity is a path to collective consciousness. In the same chapter that begins with marches and drills, Jonathan Haidt goes on to discuss ecstatic mass dancing, awe in the presence of nature, hallucinogens, and raves. One of the roles of conformity, in other words, is to enable humans to access a “hive switch” that flips our identity from individualist to collective. The term “collective” often has negative connotations (like conformity itself), until one realizes that it also implies (as McNeill points out) selflessness and trust.

Writing in The Origins of Virtue, Matt Ridley emphasizes a similar point. One of the grand puzzles of human nature is that–alone of all animals in existence–we have the capability to come together in large groups to work for collective goals without close genetic ties.[ref]Ant colonies and bee hives work together, but they are also all (effectively) siblings, and so there is no mystery here, genetically speaking.[/ref] In his book, he surveys a lot of literature on evolutionary psychology and game theory trying to explain why it is that human beings, in practice, are able to escape the prisoner’s dilemma. The prisoner’s dilemma is the most famous game theory scenario, and it proves that–if humans were strictly self-interested and rational–we would effectively never cooperate in large groups. And yet, we do cooperate in large groups. Is there any theoretically explanation for this? Yes, it turns out, there is. The only kind of society in which cooperative strategies can survive without being overwhelmed by cheating free-loaders is a conformist society.

There is one kind of cultural learning that makes cooperation more likely: conformism. If children learn not from their parents or by trial and error, but by copping whatever is the commonest tradition or fashion among adult role models, and if adults follow whatever happens to be the commonest pattern of behavior in the society—if in short we are cultural sheep–then cooperation can persist in very large groups.[ref]The Origins of Virtue, page 181[/ref]

So, instead of just making fun of non-conformists for also being conformists, it’s worth keeping in mind that conformity is a route to selflessness and, perhaps, the key to humanity’s unique ability to successfully cooperate in large, unrelated groups. But, if that’s not enough, keep in mind that things like language itself only work because of conformity. If we all tried to be non-conformists in our language, then communication would be literally impossible.

This was a long digression, but it’s something I’ve been meaning to get around to for a while anyway. To get things back on track: I don’t think non-conformity is a laudable goal in itself, but I do think that diversity matters a lot. I worry about echo chambers and I worry about group think and I worry about bubbles. And I worry about that eighth person, sitting at the table, staring at the line, wondering what on Earth could be happening that everyone else is reporting a reality that is the opposite to what he feels. I’m not really worried about whether or not this person gives the correct answer (more on that at the end), but I am very worried that this person feel empowered to give their honest answer.

This is what I had in mind when I recently read an older Slate Star Codex piece: All Debates Are Bravery Debates. In the piece, Scott Alexander argues for being charitable about extreme positions as follows:

Suppose there are two sides to an issue. Be more or less selfish…

There are some people who need to hear both sides of the issue. Some people really need to hear the advice “It’s okay to be selfish sometimes!” Other people really need to hear the advice “You are being way too selfish and it’s not okay.”

It’s really hard to target advice at exactly the people who need it. You can’t go around giving everyone surveys to see how selfish they are, and give half of them Atlas Shrugged and half of them the collected works of Peter Singer. You can’t even write really complicated books on how to tell whether you need more or less selfishness in your life – they’re not going to be as buyable, as readable, or as memorable as Atlas Shrugged. To a first approximation, all you can do is saturate society with pro-selfishness or anti-selfishness messages, and realize you’ll be hurting a select few people while helping the majority.

In terms of explanation, Scott Alexander is right on the money. He says, for example:

This happens a lot among, once again, atheists. One guy is like “WE NEED TO DESTROY RELIGION IT CORRUPTS EVERYTHING IT TOUCHES ANYONE WHO MAKES ANY COMPROMISES WITH IT IS A TRAITOR KILL KILL KILL.” And the other guy is like “Hello? Religion may not be literally true, but it usually just makes people feel more comfortable and inspires them to do nice things and we don’t want to look like huge jerks here.” Usually the first guy was raised Jehovah’s Witness and the second guy was raised Moralistic Therapeutic Deist.

That sounds familiar, and I think we all have friends who used to be really extreme in one direction, and now they’ve gone overboard in the other extreme.[ref]In The Bonobo and the Atheist, Frans de Waal pokes fun at New Atheists in general and Christopher Hitchens in particular: “Some people crave dogma, yet have trouble deciding on its contents. They become serial dogmatists.” (page 89)[/ref] Where I disagree with Scott Alexander, however, is in accepting that this kind of overreaction is basically acceptable. In my experience, both Ayn Rand (who says greed is good) and Peter Singer (who argued against any special concern for family members[ref]Frans de Waal, also in The Bonobo and the Atheist, points out that when Singer’s mother actually did become gravely ill he used his money to hire private care for her in direct contradiction of his own dogmatic utilitarian ideology. Singer said “perhaps it is more difficult than I thought before, because it’s different when it’s your mother.” De Waal commented: “The world’s best-known utilitarian thus let personal loyalty trump aggregate well-being, which in my book was the right thing to do.” (page 184-185)[/ref]) are just plain bad. I don’t care how selfish you are, Peter Singer is still overkill. I don’t care how selfless[ref]In a pathological sense.[/ref] you are, Ayn Rand is still crazy.

So this is the world I find myself in. When I look around, I feel like the eighth guy at the table on several issues. To pick just one that we talk about a lot here at Difficult Run, go with minimum wage. I’m looking at the discussions around me,[ref]I don’t mean our commenters here at Difficult Run. I think you guys are pretty great. I mean the debates as I see them unfolding on my Facebook feed, etc.[/ref] and I just can’t really believe what I’m hearing.

But when I look around for people who will stand up with me and dissent, what I see is a lot of what Scott Alexander is describing. Take “socialism.” The term, in almost all debates you will see today, has no solid meaning. It’s just a flag. And on one side you’ll see these “taxation is theft” ultra-libertarians charging against the flag of socialism and on the other side you’ll see all these people who seem to have forgotten the second half of the twentieth century rallying around the flag of socialism. Maybe some of the “taxation is theft” folks escaped Soviet oppression (as Ayn Rand did, not by coincidence) and a lot of the “Mao? Stalin? Who were they?” socialists do come from elite backgrounds in the world’s leading capitalist economy, so “to a first approximation” their points are valid. That doesn’t mean they are actually helping matters when they add their extreme, absolutist viewpoints to the discussion. Technically, the “taxation is theft” guys are going to side with me to oppose minimum wage hikes, but I really wish they wouldn’t.

Too often it seems like your choices are either (1) conform to the political fad of the day or (2) engage in extreme, overreactions. Pick your poison.

But I don’t want to pick my poison.

I don’t, for example, want to have to pick and choose between conformity and diversity. I value both. Conformity is essential for language, is vital for social cohesion, and is–in short–the glue that holds the fabric of our society together. Anyone who says they are a nonconformist is lying or a sociopath, just like anyone who says that they don’t care what other people think about them is lying or a sociopath. Everyone is a social animal, everyone cares what (some) other people think, and everyone conforms (to some group). But if you overemphasize conformity, then you get group-think. You stifle creativity, restrict free inquiry, stifle scientific curiosity, and hamstring debate and compromise. We need diversity, too. We need both.

Here’s the reason I wrote this post. Here’s the thing that Gimbel said, about the Asch experiments, that really stood out. What did it take to empower that eighth person to answer honestly? They didn’t need anything extreme. They didn’t need any theatrics. They didn’t need Ayn Rand and they didn’t need Peter Singer. All it took was one person just calmly, quietly validating what they saw.

In Asch’s experiment, the truth was obvious. In the real world, on most issues where there is a lot of debate, the truth isn’t obvious. What’s more, I’m going to be publishing a post (hopefully soon) called “Nobody Gets It All Right” that will say just that: based on my understanding of history and various biographies, everybody is wrong about most of what they believe. And I take that to heart. I have a lot of opinions. Most of them are probably wrong, at least in the sens that–two decades or two centuries from now–the things I think are true will be either discredited or (more likely) irrelevant.[ref]Don’t get too excited. The same is true for you, too.[/ref]

So I do want to dissent. I do want to raise my voice–calmly, politely, modestly–and say that the emperor’s got no clothes on when it appears to me that the emperor, in fact, does not have clothes on. But the basis of my dissent is not “I am confident that I am right.” At this point in my life, that conviction alone is not enough to stir me to publish a post. Instead, my motivation is something like, “I am dedicated to living in the kind of world where people speak their minds honestly.” Because, if I have to pick just a few areas where I want to place a very high degree of confidence–like only two or three–that’s going to be one of them.

There’s a bit of conventional wisdom about Internet debating. The point of the debate is never to persuade the other guy. The debate is always for the sake of the audience. There’s truth to that, but it can be taken too far, and made into a philosophy where arguing online is a gladiatorial spectator sport with both sides essentially playing to their respective fan bases with no interest in sincere, honest interaction with each other’s points. That’s not what I want to do.

Instead, I just want to be the one guy at the table who says, “I see things differently” that thereby enables the eighth guy to have an easier time in saying the same thing.

That, in a nutshell, is one of the fundamental reasons Difficult Run exists.

This is a great post. Thanks.

Thanks, Margot.

“Everyone is a social animal, everyone cares what (some) other people think, and everyone conforms (to some group).”

This is true to a point. I think the social factor will vary wildly too based upon your temperament. I have been listening to a book “the introvert advantage” and I would say that introverts have a less need to socialize or be part of SOMETHING.

Introverts get plenty of there satisfaction from themselves and not as much from others.

A lot of time the need to conform comes because of fear or reward but if you can live with the fear or without the reward then so goes the conformity requirement.

Outside of mathematical proofs, that’s how basically everything is true. :-)

Look, introverts (I am an introvert, my wife even more so) may have less of a desire to conform, but “less” it not “none”. All humans–even introverts–are essentially social animals. We are all parts of communities. None of us exist in isolation. And part of being in a community–part of the definition of a community–is having certain conventions in common, from clothing to language.

I think if you consider how even extreme introverts behave, you will realize that, overwhelmingly, they are conformist. The language they use, the clothes they wear, the food they eat, the entertainment they consume, their habits of sleeping and waking and working, their reliance on fiat currency, their interaction with relevant legal systems, their participation in formal institutions like schools, etc. Sure, on a couple of metrics they will stand out, but the reason that they will stand out is because, on all the others, they conform.

The problem is that we conform so much of the time to so many things that it becomes invisible to us. Just think of basic etiquette rules, things like not interrupting people or the way you sit or stand in relation to others in social settings, etc. and you will realize that non-conformity on these matters is basically equivalent to serious mental instability. Conformity is the rule, not the exception.

First, the humorous part of the reply: the line length experiment reminded me of this video that I saw yesterday: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTezdMLJoyE

The idea of just needing one person to agree with you to validate your dissent is interesting in the context of a single issue, but how do you think it expands (or was anything said about how it expands) in the context of multiple issues? I’m thinking along the lines of discussions on my Facebook feed as well–there are lots of posts I see that I don’t really agree with, or think are too extreme, but were I to say so I would be piled on by everybody else; but on the other hand, if my feed were reorganized to a different group of friends, I would almost definitely find myself equally unwelcome among discussions and opinions on the other extreme. And so while person A may validate your dissent on a particular topic, it seems that could easily alienate you from those who may validate you when dissenting against person A on something else.

(Whew, that was a jumbled thought, but I think I got the point across…)

Dan-

Studio C is always classic! Great video.

I think I totally get what you’re saying, and that’s actually a point that Scott Alexander (from Slate Star Codex) made as well: whether your point of view is a dissenting one depends on which group you’re in. Scott’s approach was to try and figure out which way society as a whole is tilting and then counteract it, thus he said that he’s more right-wing than his social circle, but more left-wing than the country as a whole.

I’m skeptical about whether or not we can (1) know accurately where the entire country is on many issues and (2) even really talk about the “country’ having an opinion. Networks are not homogenous, like graph paper, with every node (person) connected to an equal number of other nodes (more people) through a set of repetitive connections. Social networks have clusters and regions and neighborhoods.

So, for me, it’s important to try and do two things:

1. Be a dissenting voice in your actual community. Now, you shouldn’t change your opinion just to be contrary, but you should know your audience. If everyone around you is already convinced on the same point that you are, then maybe don’t write about it as much. Maybe find something where, even if you do agree with a lot of the people in your network, there’s room for some nuance, or revision, or modification, And write about that. And definitely write about the things where you and your network disagree.

2. Look for issues where it looks like there is a high cost to dissent, and make your voice heard there. That is why we tend to touch on hot-button issues at DR. I’ve written a lot about social justice because my perception is that this is an issue where you really risk getting hit hard if you dissent. I’ve also written about gay marriage and human sexuality because, again, my sense is that (at least in the circles I travel: college-educated professionals) there’s a growing authoritative dogma on these views. In fact, documenting the bias is one of the most important part of tackling those issues.

We can’t ever be sure that we’re correct in our assessment of what views are or are not popular in our own social circles or in the world at large. But for me the goal is to try and talk about (1) things that matter, (2) where there is a risk that a perspective is being silenced, (3) in ways that are not just preaching to the choir.

I’m not sure I always live up to that. I’ve attacked Trump twice and, frankly, basically nobody I know likes the guy. Maybe I can be forgiven in that case because the’s a real sense that nationally he does have momentum (so there is a real sense in which dissent matters), but at least in a local sense, those articles were basically preaching to the choir.

Still, I do try–and so do all the writers at Difficult Run–to skew towards picking topics that are going to be a little contrarian, but not just for the sake of being provocative.

Did I respond well to your comment, or totally miss the point?

Yeah, that generally speaks to what I was getting at. I realized it was possible that it was discussed in some article you had linked, but frankly, your pieces often already border on tl;dr for when I’m at work, so I didn’t really have time to click through to others ;) (And it’s not helped by the fact that I spend so much time thinking and rethinking responses to try to make them as clear as I can, even if I don’t always succeed at it…)

I guess another way of looking at it is that it’s one thing to say “in this case with a blindingly obvious, factually correct answer, it’s hard to go against the consensus, but one person’s support is enough to dissent against the group,” but it’s much more challenging in everyday life. As you pointed out, social networks are not uniform, and neither are opinions, and especially on hot-button/high-cost-of-dissent issues it can be much riskier. If, as one of my professors used to say, you have the strength of your convictions, maybe that also makes it easier; if you’re more prone to conflict avoidance (like me), then it might take not just one supporting voice, but multiple, and/or voices with enough social capital in a given network.

As a modification of the line experiment, what if they told the subject “this person is trustworthy, this person is a pathological liar?” If the known liar is the only one who supports you, I wonder if you are more or less likely to fall in with the crowd? Or how would that affect the crowd’s opinion of you? I suspect the latter is much harder to study, but is also more interesting in terms of what happens when social networks collide.

Great post! The Asch experiment reminded me of one of my favorite experiences with Eugene England. I was sitting in the front row of one of his lectures and he was talking about a similar experiment only the participants were to name the color of a card which was in reality black. But the pre-warned participants were told to say it was gray. Brother England looked at me and asked me what color I would say the black card was after hearing 11 people ahead of me say it was gray. I replied, ” I’d probably say it was dark gray. Very very dark gray.” Brother England laughed. I don’t think he ever knew who I was but it was a sweet moment for me to know that I made the inimitable Eugene England laugh. Thanks for another extraordinarily thoughtful post. Love your writings.

I wonder about the influence of the internet on this issue. If you are in a position to go looking, you can find others who agree with you on virtually anything. So you’d think that would help minimize this problem, but I fear it does very little, for two reasons: first, because the people to whom it matters to most of us that we conform aren’t merely internet people, but people we interact with in person. Second, because part of what I suspect makes conformity so appealing is that it shields us from even considering other options–it’s cognitively much simpler.

I suspect that many of us would discover that we dissent only upon being presented with a dissenting view. Were that never made salient to us, we’d never clearly entertain the question of whether to conform or dissent, and it might never occur to us that there was something we were choosing to give up by conforming. It would just seem like those sacrifices were unavoidable and not worth carping about or trying to avoid. Indeed, I suspect that one of the things which can make fiction seem insightful is the presentation of an unfamiliar dissent with which some of us find ourselves agreeing.

Therefore, it’s important for as many people as possible to read Difficult Run. I admit, I could just as easily have started from that conclusion and reasoned backward. Y’all do good work, and this post was a nice example.

John Adams would love this post.

Therefore, it’s important for as many people as possible to read Difficult Run. I admit, I could just as easily have started from that conclusion and reasoned backward. Y’all do good work, and this post was a nice example.

Thanks, Kelsey. That’s high praise indeed. I’m glad you think we’re doing good work.

John Adams would love this post.

Also high praise, Daniel! Probably not much higher. I really didn’t know how this piece would be received. I’m happy that it’s resonating with folks.

Speaking of collective consciousness, I think it goes both ways. When we look at the greatest non-conformists, the artists, heroes and scientists that challenged and changed the world, we see within them archetypal patterns which can be found in embedded in every soul, no matter how conformist: the rebel, the inventor, the magician, the prophet, the poet, the Christ figure. We respond to these heroes because we see them roleplaying patterns that resonate with our own identity, even though we may never exhibit the archetypes as strongly as these individualists.

Of course there are important conformist archetypes, and maybe these archetypes should be the dominant ones in society: mother, father, son, daughter, citizen, disciple, servant, etc. Maybe we need more disciples than prophets.

But the disciple follows the prophet perhaps not because he is a follower, but because he hears the stirrings of the prophet archetype within himself. It looks like conformity, but I’m not sure it really is.