The above chart from the Economic Policy Institute has become a staple in the “wage stagnation” debate. I talked about it before a couple years ago, but I thought I’d revisit it since there have been a couple responses to the EPI since then. Scott Winship, formerly of Brookings and now at the Manhattan Institute, writes,

The Economic Policy Institute (EPI)…has created a widely cited chart indicating that productivity rose 72 percent during 1973–2014 while median hourly compensation rose by a measly 9 percent. The implication is that rising inequality and declining employer generosity mean that policies that promote economic growth will fail to lift middle-class living standards and that more redistribution is necessary to assist working families.

In arriving at this conclusion, EPI makes numerous faulty methodological decisions. It understates growth in median hourly compensation by using a deficient inflation adjustment and by undervaluing benefits other than health insurance. It overstates the divergence between productivity and median hourly compensation trends by using different inflation adjustments for each. It includes imputed rents in national income, which exerts a downward pull on labor’s share of income. It includes the self-employed in its analyses, for whom it makes little sense to distinguish between labor income and capital income. And it includes government and nonprofit workers, whose productivity is not well measured (pg. 4).

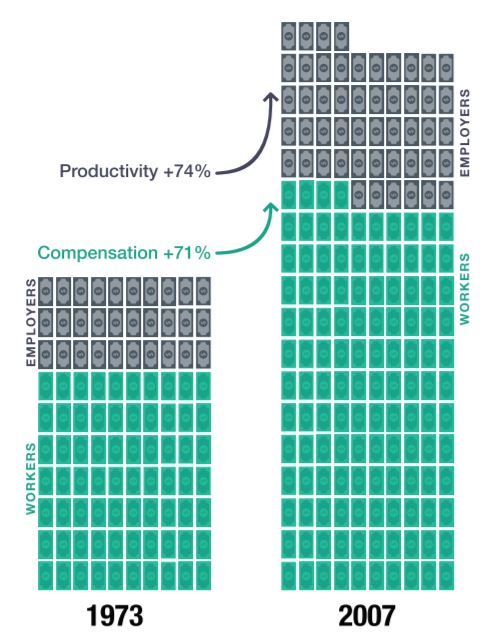

Winship instead finds the following:

- During 1973–2007, U.S. hourly compensation rose 71 percent, while productivity rose 74 percent.

- In 1973, U.S. workers received 70 percent of the income produced by businesses; in 2007, they received 69 percent.

- For the past 70 years, labor’s share of income has fluctuated—almost without exception—between 67 percent and 71 percent.

- Since 1929, the U.S. business cycles with the highest productivity growth have also featured the highest growth in hourly compensation.

- Male and female middle-class workers saw faster growth in pay during 1989–2000 and 2000–07 than during 1973–79, when productivity growth was slower.

- Middle-class pay has not stagnated: during 1997–2011, productivity rose by 35 percent, aggregate compensation rose by 32 percent, median hourly compensation increased by 20 percent, median female pay climbed by 25 percent, and median male pay grew by 18 percent.

According to the Heritage Foundation’s James Sherk,[ref]Before dismissing Heritage as Koch-bought, right-wing hackery, it might be worth pointing out that 27% of the EPI’s funding comes from unions and its Board of Directors chairman is the president of AFL-CIO. Heritage isn’t my go-to source for much of anything, but this is the most in depth analysis I’ve read of the EPI’s claims.[/ref]

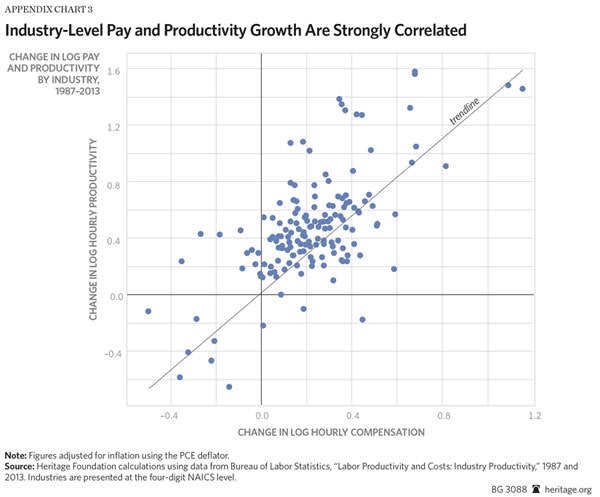

Academic economists largely reject this analysis and the conclusion that salary no longer grows with productivity. Harvard professor Martin Feldstein, the former president of the National Bureau of Economic Research, concluded that the apparent divergence results from comparing the wrong data. Using the correct data, he finds that pay and productivity have both grown together. Staff at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis found the same result.

Even prominent liberal economists who have examined this question agree. Dean Baker, director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, finds that pay growth tracks productivity growth when comparing the same groups of workers and using the same measure of inflation. Harvard professor Robert Lawrence served on President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers; he comes to the same conclusion. George Washington University professor Stephen Rose—a former Clinton Administration Labor Department official currently affiliated with the Urban Institute—likewise finds that the apparent gap between pay and productivity collapses under scrutiny. He concludes that productivity growth continues to benefit working Americans.

Most economists who examine the issue conclude that firms pay workers according to the value they produce.

In my view, one of the most glaring errors of the EPI’s methodology is the following:

EPI compares compensation for production and non-supervisory employees—which covers about five-eighths of the total economy—to the productivity of all workers in the economy. Economic theory does not predict that the pay and productivity of different groups of employees will necessarily track each other, especially in the presence of barriers to mobility.

Even abstracting from analytical errors, EPI can claim no more than that pay and productivity have grown differently among different groups of workers. EPI’s data say nothing about whether workers’ pay has grown in step with their own productivity.

Check out the full analyses by both Winship and (especially) Sherk.