According to a 2016 Fast Company article,

Nearly a third (32%) of employers are bumping up education requirements for new hires. According to a new survey from CareerBuilder, 27% are recruiting those who hold master’s degrees for positions that used to only require four-year degrees, and 37% are hiring college grads for positions that had been primarily held by those with high school diplomas.

CareerBuilder conducted a nationwide online survey that culled responses from over 2,300 hiring and human resource managers across different industries in the private sector.

Their responses revealed that employers pushing their education requirements toward higher degrees are doing so across all levels of their companies. The majority of employers (61%) say they are looking for more educated candidates at the mid-level skill level, but 46% are looking to hire better educated candidates at entry level and 43% think the same for higher levels.

This comes at a time when the cost of a four-year college degree is out of reach for the average American family. But employers argue that a tight job market and evolving need for different skills are making it necessary. For example, 60% of employers who were satisfied with hiring high school graduates in the past claimed their work requires the skills held by those who have completed higher education.

But why?

Employers told CareerBuilder that higher education not only increases an applicant’s chance of getting hired, but it helps boost the chance they’ll be promoted down the road. Thirty-six percent of employers reported that they would be unlikely to promote someone who doesn’t have a college degree.

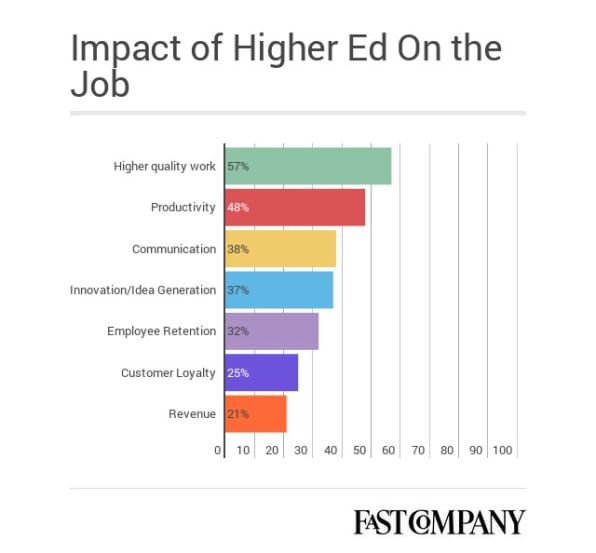

That’s because employers have seen education make a positive impact across the board, from employees’ ability to produce better quality work, to productivity and the ability to boost customer loyalty.

This is likely why a “recent Pew Research study found that high school graduates earn about 62% of what those with four-year degrees earn. That’s evolved since 1979, when people with only high school educations earned 77% of what college graduates made.” But not all is lost:

The good news for current and future workers is that some companies are taking responsibility to bridge the skills gap and overcome the talent shortage. Over a third of employers (35%) said they trained low-skill workers and hired them for high-skill jobs in 2015, and 33% said they’ll do the same this year. A full 64% of employers said they plan to hire people who have the majority of skills they require and provide training for the rest. They’ll do this by paying for training and certifications offered outside the company or sending them back to school. Twenty-three percent said they would fund an advanced degree partially, and 12% would foot the entire bill.

Fast Company recently reported that a small, but growing number of companies are offering employees assistance to pay back their student loans.

This could be an example of business leaders compensating for what they see as a lack of preparation among new college graduates. Furthermore, it may be an argument in favor of greater collaboration between higher education institutions and businesses.