Oxford’s Max Roser has provided a much-needed ray of sunshine given the past week’s events. Roser writes,

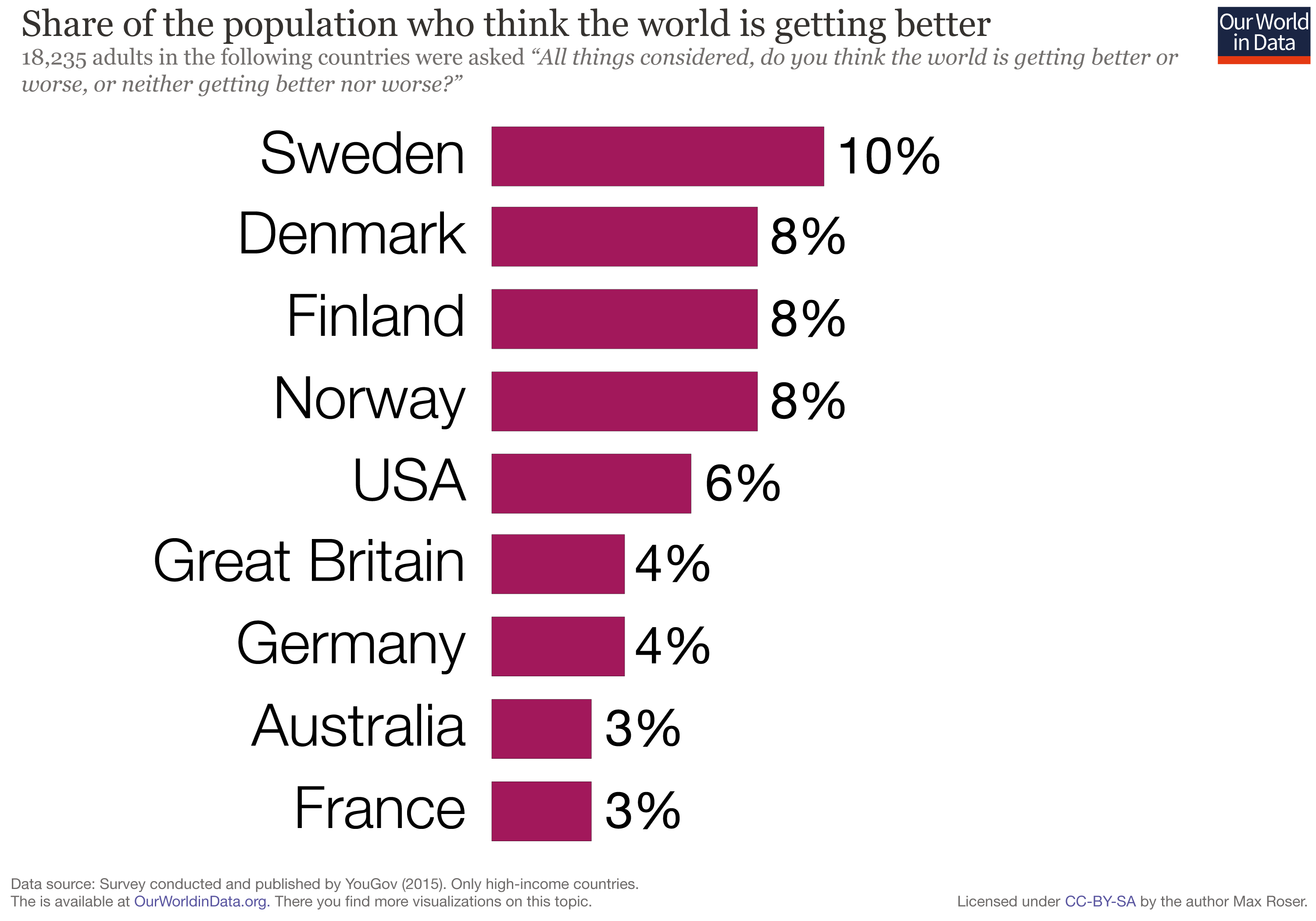

A recent survey asked “All things considered, do you think the world is getting better or worse, or neither getting better nor worse?”. In Sweden 10% thought things are getting better, in the US they were only 6%, and in Germany only 4%. Very few people think that the world is getting better.

What is the evidence that we need to consider when answering this question? The question is about how the world has changed and so we must take a historical perspective. And the question is about the world as a whole and the answer must therefore consider everybody. The answer must consider the history of global living conditions – a history of everyone.

Roser tackles several issues, but I’ve selected just four:

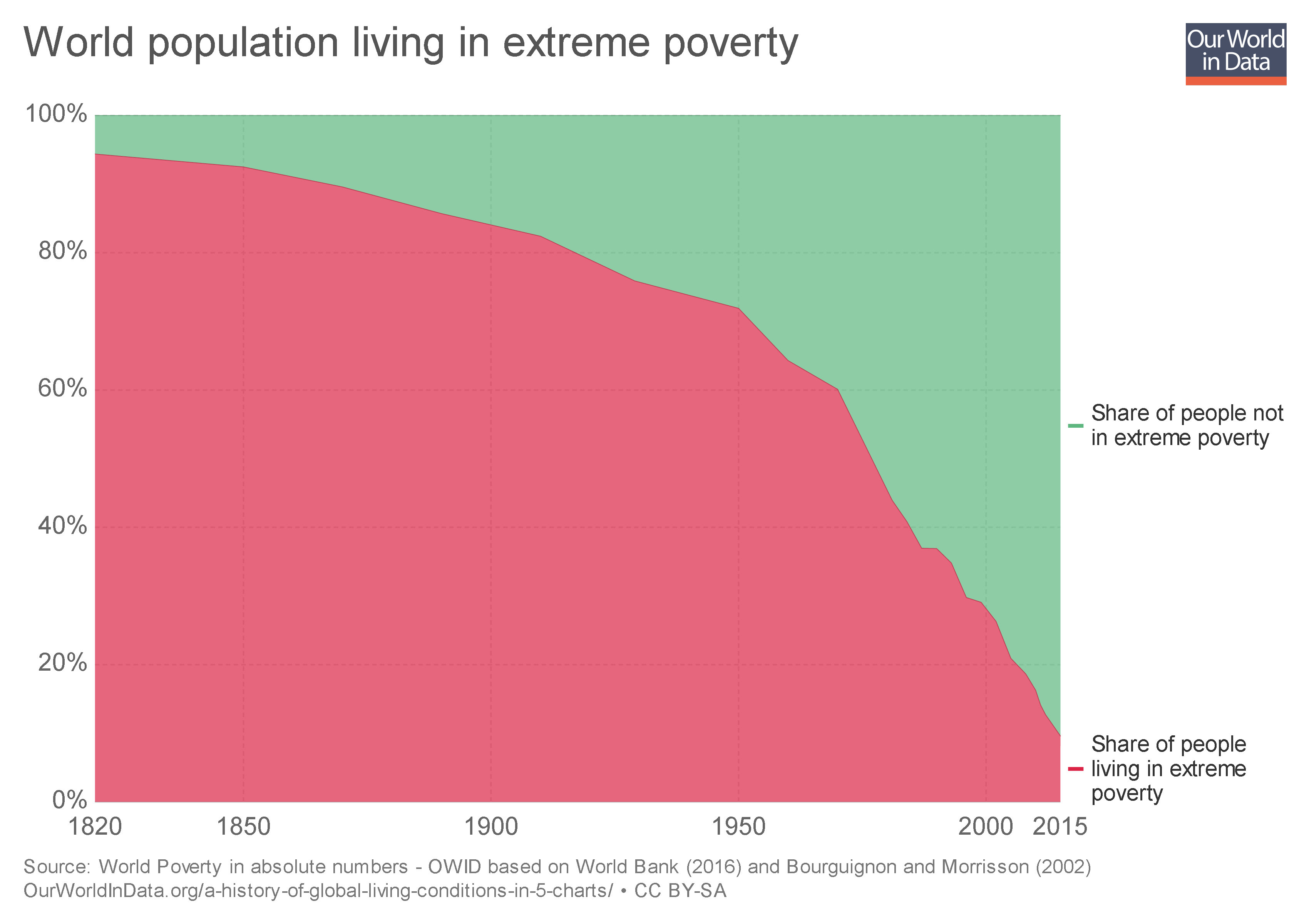

- Poverty: “Take a longer perspective and it becomes very clear that the world is not static at all. The countries that are rich today were very poor just very recently and were in fact worse off than the poor countries today. To avoid portraying the world in a static way – the North always much richer than the South – we have to start 200 years ago before the time when living conditions really changed dramatically…The first chart shows the estimates for the share of the world population living in extreme poverty. In 1820 only a tiny elite enjoyed higher standards of living, while the vast majority of people lived in conditions that we would call extreme poverty today. Since then the share of extremely poor people fell continuously. More and more world regions industrialised and thereby increased productivity which made it possible to lift more people out of poverty: In 1950 three-quarters of the world were living in extreme poverty; in 1981 it was still 44%. For last year research suggests that the share in extreme poverty has fallen below 10%.”

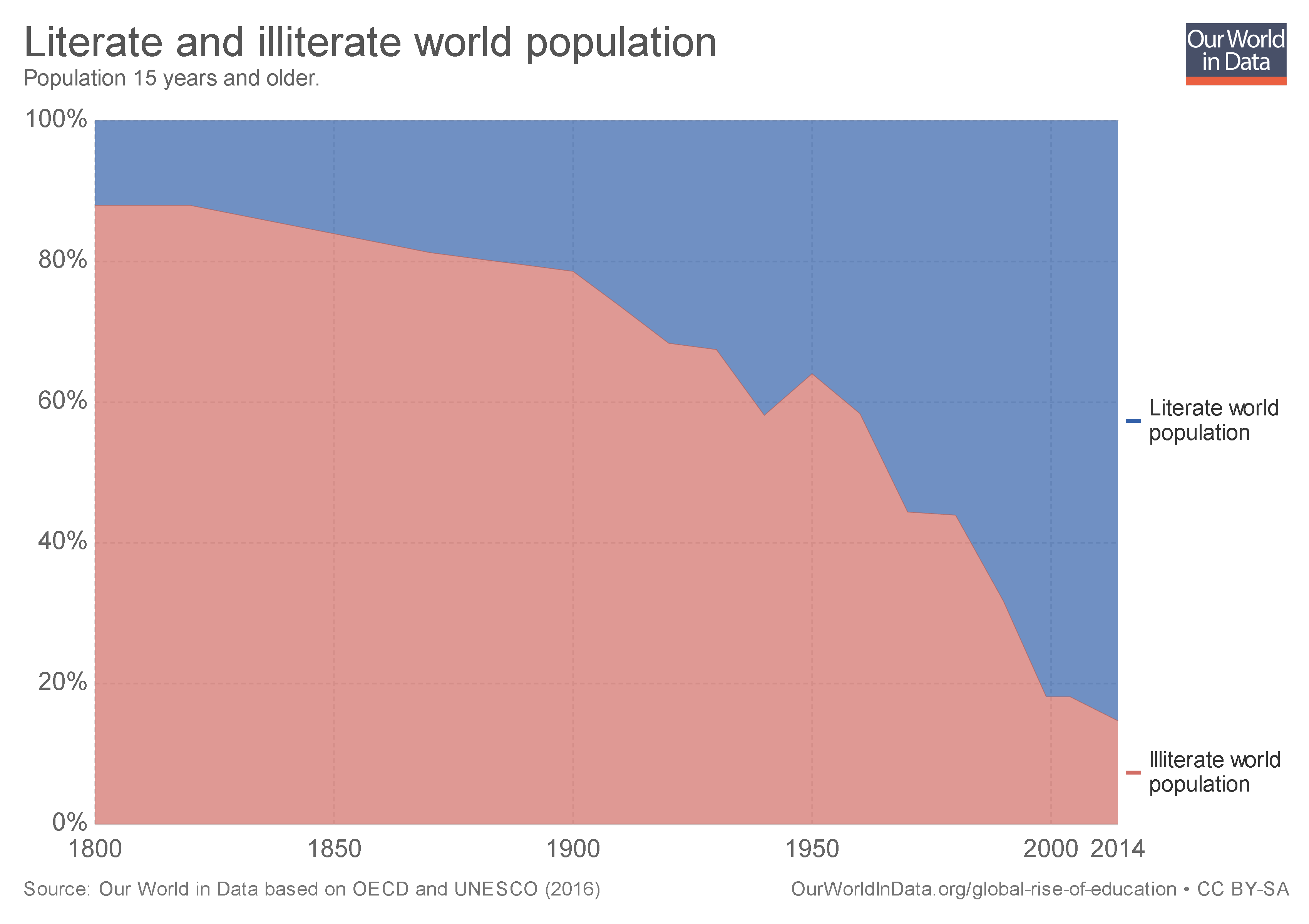

- Literacy: “How did the education of the world population change over this period? The chart below shows the share of the world population that is literate over the last 2 centuries. In the past only a tiny elite was able to read and write. Today’s education – including in today’s richest countries – is again a very recent achievement. It was in the last two centuries that literacy became the norm for the entire population.”

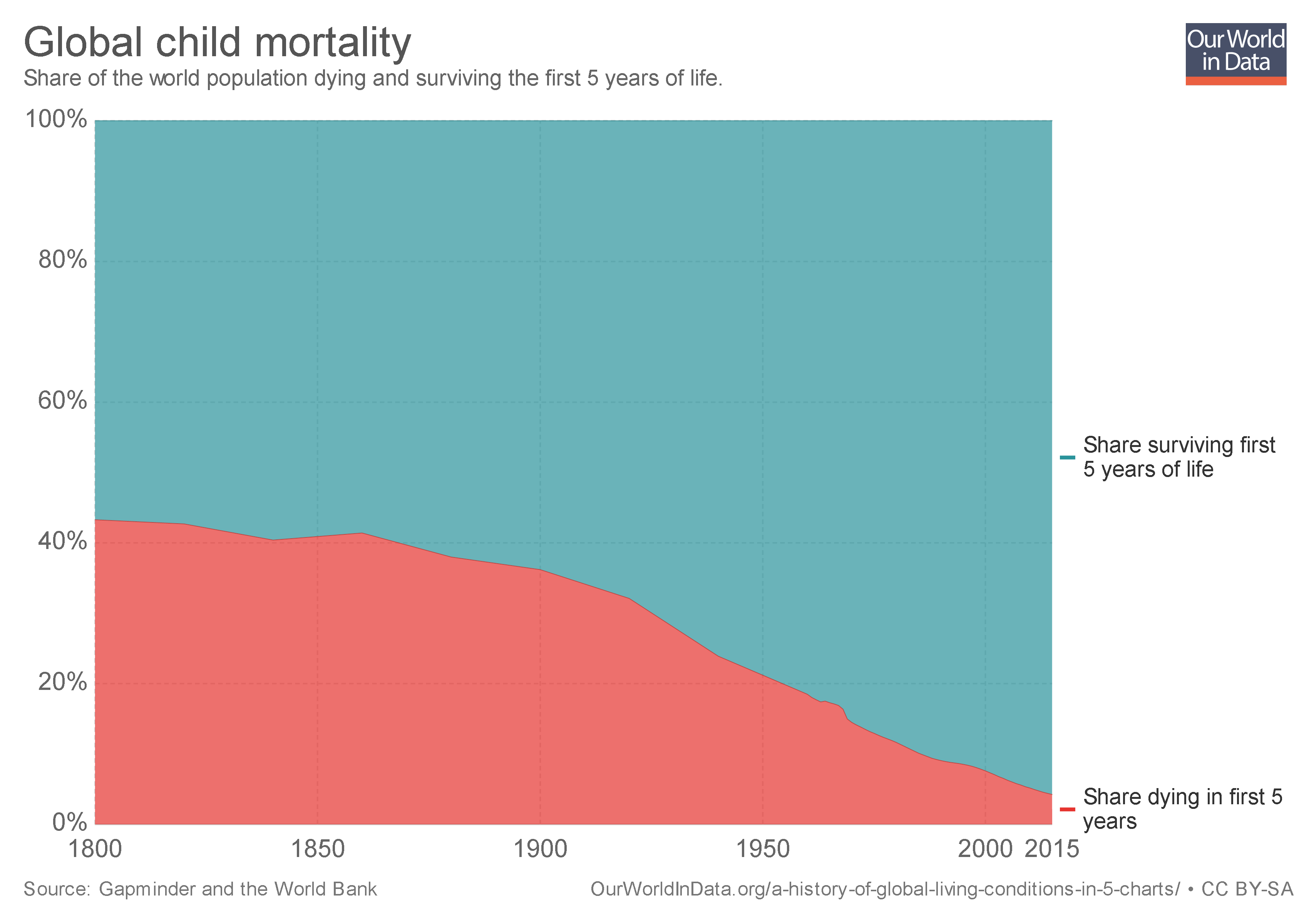

- Health: “In 1800 the health conditions of our ancestors were such that around 43% of the world’s newborns died before their 5th birthday. The historical estimates suggest that the entire world lived in poor conditions; there was relatively little variation between different regions, in all countries of the world more than every third child died before it was 5 years old…In 2015 child mortality was down to 4.3% – 10-fold lower than 2 centuries ago. You have to take this long perspective to see the progress that we have achieved.”

- Freedom: “Political freedom and civil liberties are at the very heart of development – as they are both a means for development and an end of development…The chart shows the share of people living under different types of political regimes over the last 2 centuries. Throughout the 19th century more than a third of the population lived in colonial regimes and almost everyone else lived in autocratically ruled countries. The first expansion of political freedom from the late 19th century onward was crushed by the rise of authoritarian regimes that in many countries took their place in the time leading up to the Second World War. In the second half of the 20th century the world has changed significantly: Colonial empires ended, and more and more countries turned democratic: The share of the world population living in democracies increased continuously – particularly important was the breakdown of the Soviet Union which allowed more countries to democratise. Now more than every second person in the world lives in a democracy. The huge majority of those living in an autocracy – 4 out of 5 – live in one autocratic country: China. Human rights are similarly difficult to measure consistently over time and across time. The best empirical datashow that after a time of stagnation human right protection improved globally over the last 3 decades.”

Roser concludes,

For our history to be a source of encouragement we have to know our history. The story that we tell ourselves about our history and our time matters. Because our hopes and efforts for building a better future are inextricably linked to our perception of the past it is important to understand and communicate the global development up to now. A positive lookout on the efforts of ourselves and our fellow humans is a vital condition to the fruitfulness of our endeavors. Knowing that we have come a long way in improving living conditions and the notion that our work is worthwhile is to us all what self-respect is to individuals. It is a necessary condition for self-improvement.

Freedom is impossible without faith in free people. And if we are not aware of our history and falsely believe the opposite of what is true we risk losing faith in each other.

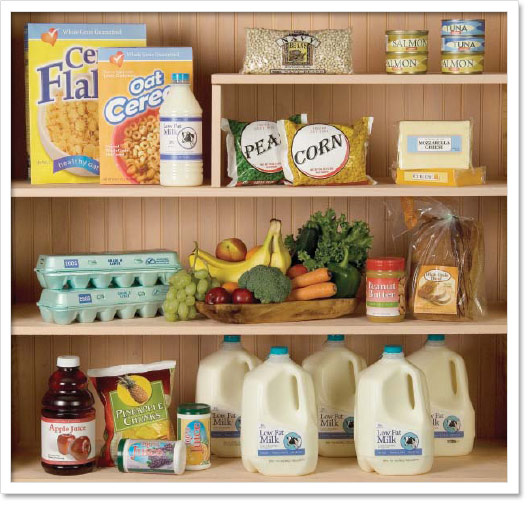

Some of the foods you can purchase through WIC.

Some of the foods you can purchase through WIC. The controversial Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson has a new book out titled

The controversial Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson has a new book out titled