A few years ago, I linked to a Wall Street Journal op-ed by economist Hernando de Soto that declared “economic hope” to be “the only way to win the battle for the constituencies on which terrorist groups feed.” A couple years later, I discussed the possibility that strict labor laws–and the unemployment it produces–was a major contributor to radicalization in Europe. In short, the lack of economic opportunity breeds extremism.

Recent evidence appears to support this hunch.

Many point to U.S. drone strikes as a causal factor in Islamic radicalization. However, a brand new study argues the contrary, concluding,

Although U.S. drone strikes in Muslim countries might play a role in the radicalization or violent extremism of co-religionists around the world, the available evidence does not support the assertion that drones are “fueling the fires of homegrown radicalization” in Western societies or that these unmanned aerial vehicles are the new Guantánamo.

…The radicalization of individuals in the Somali diaspora, especially in the state of Minnesota, illustrates the role of U.S. policies targeting Muslim communities at home; personal factors, such as conflicted identities among young Somali Americans; and their nationalist desire to evict foreign troops from Somalia, a desire that recruiters from the al-Qaida affiliate al-Shabaab have been able to exploit. My brief examination of the social science literature on the drivers of Islamist militancy among Muslims in European countries similarly points to domestic factors such as an identity crisis among some young Muslims, state policies of marginalization and discrimination, and the role of radical preachers and terrorist recruiters who leverage these vulnerabilities for recruitment (pg. 83-84; emphasis mine).

This is further confirmed by a recent World Bank paper:

Exploiting individual-level education information for these fighters, we link the size of a contingent of fighters to the economic conditions faced by workers in their countries of residence who have the same level of education, by distinguishing primary, secondary and tertiary education. Beginning non-parametrically, we document a correlation between the within-country relative unemployment rate faced by workers from a specific country and education level and the corresponding relative number of recruits. We then conduct panel regressions in which we estimate the impact of unemployment on the propensity to join the terrorist group, controlling for country and education-level fixed effects. The estimated coefficients indicate that higher unemployment rates are a push factor towards radicalization, especially for countries at a shorter distance to Syria, with an elasticity of 0.25; a one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate leads to 42 additional Daesh recruits. The elasticity steeply decreases further away from Syria and becomes both economically and statistically insignificant past the average distance of 2,500 km. The results are robust to the inclusion of education-specific wage rates, strengthening the case for a causal interpretation of these results (pg. 1-2).

I’m reminded of the famous quote by Nobel laureate Robert Lucas: “The consequences for human welfare involved in questions [of economic growth] are simply staggering: Once one starts to think about them, it is hard to think about anything else” (pg. 5).

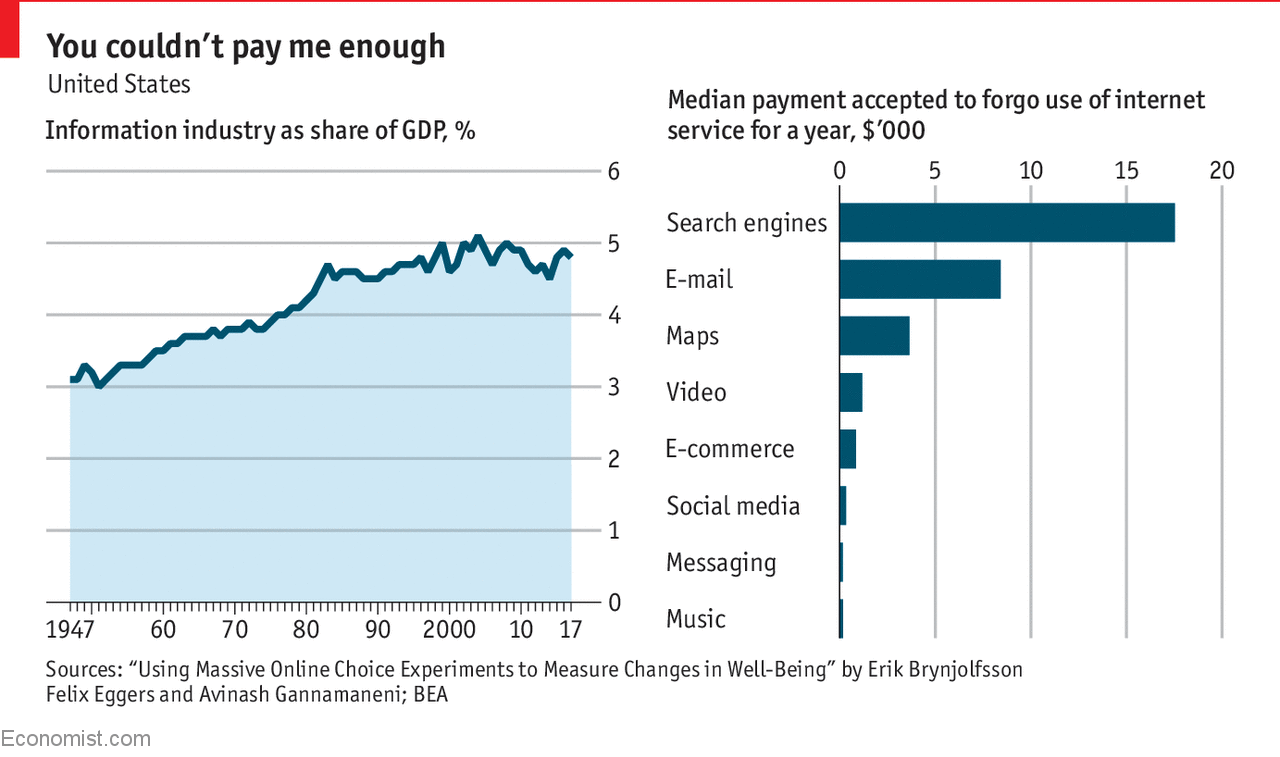

Assessing the size and identifying the sources of gains from trade is a long-standing challenge for economists. Theoretical and quantitative studies have mostly focused on static economies where changes in international market integration have only one-off effects on the levels of income and consumption but do not affect the long-run dynamics of these key economic variables (Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare, 2014). Since innovation and technological change are key drivers of income growth in the long-run (Aghion and Howitt, 2009, Akcigit et al. 2017), in a recent paper (Impullitti and Licandro 2018) we explore the sources and assess the size of the gains from trade in an economy where growth spurs from technological progress.

Assessing the size and identifying the sources of gains from trade is a long-standing challenge for economists. Theoretical and quantitative studies have mostly focused on static economies where changes in international market integration have only one-off effects on the levels of income and consumption but do not affect the long-run dynamics of these key economic variables (Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare, 2014). Since innovation and technological change are key drivers of income growth in the long-run (Aghion and Howitt, 2009, Akcigit et al. 2017), in a recent paper (Impullitti and Licandro 2018) we explore the sources and assess the size of the gains from trade in an economy where growth spurs from technological progress.

Immigration policy is controversial topic in 2018. In response to refugee crises and legal situations that can break up families, the LDS Church announced its “I Was a Stranger” relief effort and released a statement encouraging solutions that strengthens families, keeps them together, and extends compassion to those seeking a better life. This article seeks to shed light on a correct understanding of immigration and its effects. Walker Wright gives a brief scriptural overview of migration, explores the public’s attitudes toward immigration, and reviews the empirical economic literature, which shows that (1) fears about immigration are often overblown or fueled by misinformation and (2) liberalizing immigration restrictions would have positive economic effects.

Immigration policy is controversial topic in 2018. In response to refugee crises and legal situations that can break up families, the LDS Church announced its “I Was a Stranger” relief effort and released a statement encouraging solutions that strengthens families, keeps them together, and extends compassion to those seeking a better life. This article seeks to shed light on a correct understanding of immigration and its effects. Walker Wright gives a brief scriptural overview of migration, explores the public’s attitudes toward immigration, and reviews the empirical economic literature, which shows that (1) fears about immigration are often overblown or fueled by misinformation and (2) liberalizing immigration restrictions would have positive economic effects. Total wealth in the new approach is calculated by summing up estimates of each component of wealth: produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and net foreign assets. This represents a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by (1) assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth and then (2) calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption…In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual.

Total wealth in the new approach is calculated by summing up estimates of each component of wealth: produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and net foreign assets. This represents a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by (1) assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth and then (2) calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption…In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual.

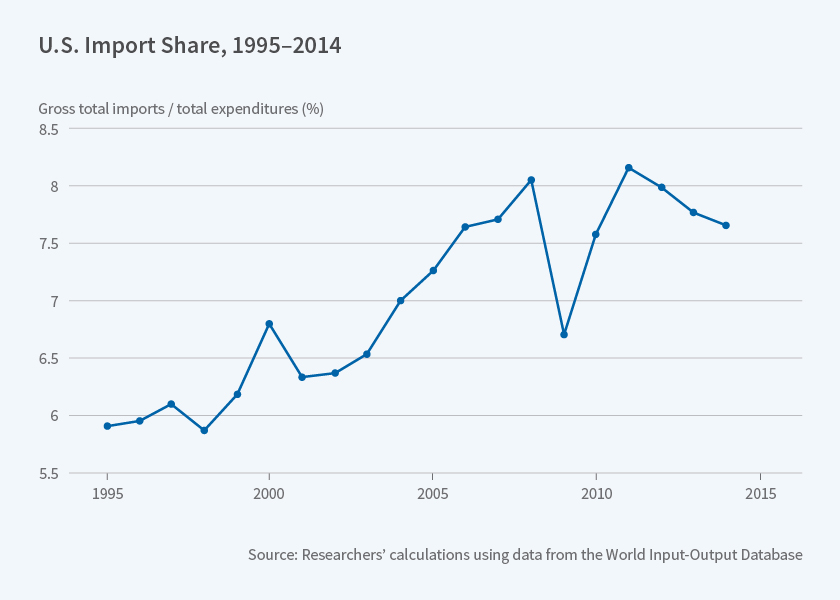

There is surprisingly little direct quantitative evidence on how the U.S. economy would react if the door were shut on trade. To find a precedent, the researchers point out that one could go back to the Embargo Act of 1807, when the United States banned trade with Great Britain and France in retaliation for their repeated violations of U.S. neutrality. GDP declined sharply, but the agrarian world during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson bears little resemblance to today’s high-tech, service-oriented economy.

There is surprisingly little direct quantitative evidence on how the U.S. economy would react if the door were shut on trade. To find a precedent, the researchers point out that one could go back to the Embargo Act of 1807, when the United States banned trade with Great Britain and France in retaliation for their repeated violations of U.S. neutrality. GDP declined sharply, but the agrarian world during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson bears little resemblance to today’s high-tech, service-oriented economy.