Last month, I posted a few links on why today’s middle-class salary may actually be better than we often think. Harvard professor and president emeritus of the National Bureau of Economic Research Martin Feldstein adds more food-for-thought on the subject:

Last month, I posted a few links on why today’s middle-class salary may actually be better than we often think. Harvard professor and president emeritus of the National Bureau of Economic Research Martin Feldstein adds more food-for-thought on the subject:

…[I]t is frequently said that the average household income has risen only slightly, or not at all, for the past few decades. Some US Census figures seem to support that conclusion. But more accurate government statistics imply that the real incomes of those at the middle of the income distribution have increased about 50% since 1980. And a more appropriate adjustment for changes in the cost of living implies a substantially greater gain.

The US Census Bureau estimates the money income that households receive from all sources and identifies the income level that divides the top and bottom halves of the distribution. This is the median household income. To compare median household incomes over time, the authorities divide these annual dollar values by the consumer price index to create annual real median household incomes. The resulting numbers imply that the cumulative increase from 1984 through 2013 was less than 10%, equivalent to less than 0.3% per year.

Any adult who was alive in the US during these three decades realizes that this number grossly understates the gains of the typical household. One indication that something is wrong with this figure is that the government also estimates that real hourly compensation of employees in the non-farm business sector rose 39% from 1985 to 2015.

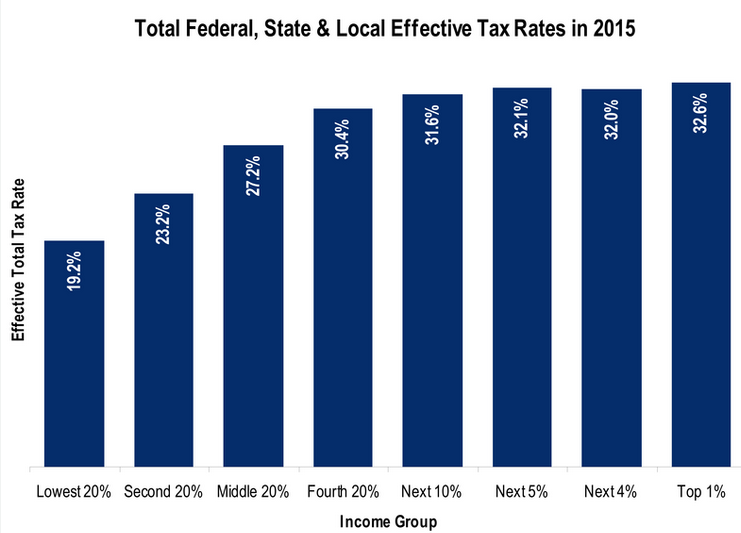

The official Census estimate suffers from three important problems. For starters, it fails to recognize the changing composition of the population; the household of today is quite different from the household of 30 years ago. Moreover, the Census Bureau’s estimate of income is too narrow, given that middle-income families have received increasing government transfers while benefiting from lower income-tax rates. Finally, the price index used by the Census Bureau fails to capture the important contributions of new products and product improvements to Americans’ standard of living.

Worth a read.

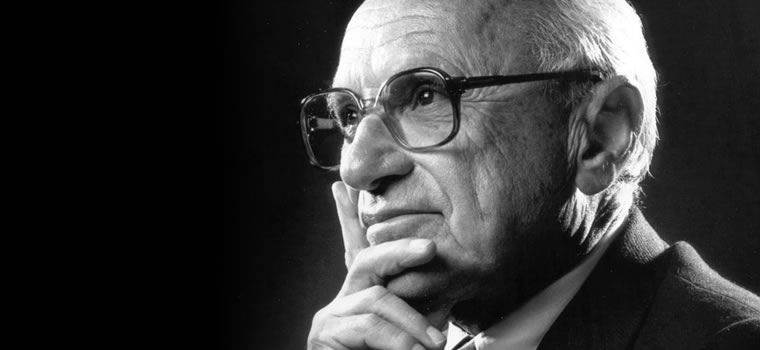

The Canada-based Fraser Institute has a new project titled The Essential Hayek. As

The Canada-based Fraser Institute has a new project titled The Essential Hayek. As