This is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

A couple months ago, I wrote a post for Times & Seasons on the personal meaning of the Atonement. I boiled it down to one major message: I’m worth something. I rest this largely on the evangelical favorite John 3:16: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” In an ancient world full of mischievous, flawed, and often indifferent gods, the idea of deity sacrificing on behalf of mortals (not the other way around) could be seen as somewhat jarring. As New Testament scholar Craig Keener explains,

Although John’s portrait of divine love expressed self-sacrificially is a distinctly Christian concept, it would not have been completely unintelligible to his non-Christian contemporaries. Traditional Platonism associated love with desire, hence would not associate it with deity. Most Greek religion was based more on barter and obligation than on a personal concern of deities for human welfare. Homer’s epic tradition had long provided a picture of mortals specially loved by various deities, but these were particular mortals and not humanity as a whole or all individual suppliants to the deity. Further, deities in the Iliad have favorite mortals, debating back and forth who should be allowed to kill whom. But they do not knowingly, willingly sacrifice themselves (though some like Ares and Artemis are wounded against their will); Hera and others back down when threatened by Zeus, and even limit their battles with one another on account of mortals (cf. Il. 21.377–380). Achilles complains that the deities have destined sorrow for mortals yet have no sorrow of their own (Il. 24.525–526). By this period, however, popular Hellenistic religion was shifting away from traditional cults toward personal experience, bringing more to the fore a deity’s patronal concern for his or her clients. Thus a few deities, especially the motherly Demeter and Isis, are portrayed as loving deities. Jewish tradition often stresses God’s abundant, special love toward the righteous or Israel…John, however, emphasizes not only God’s special love for the chosen community (e.g., 17:23), but for the world (cf. 1 John 2:2; 1 Tim 2:4; 2 Pet 3:9)…[I]n Johannine theology God’s love for the “world” represents his love for all humanity…[T]hat God gave his Son for the world indicates the value he placed on the world.[ref]Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of John: A Commentary, Vol. 1 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003), 568-569.[/ref]

I was pleased to hear Elder Ashton in his April 1973 talk[ref]I wasn’t really in the mood to listen to talks building up the importance of Church leadership, especially since the leader in question is Harold B. Lee. I just finished rereading the chapter “Blacks, Civil Rights, and the Priesthood” in Greg Prince’s David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism in which Lee plays a major role in blocking initiatives to lift the priesthood ban prior to the 1978 revelation. As Lee’s “daughter confided to a friend, “My daddy said that as long as he’s alive, [blacks will] never have the priesthood,” a prediction that proved to be correct” (Prince, Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, 64). Faith-promoting fluff like Elder Perry talking about how he has “watched [prophets] armed with the Holy Ghost as a constant companion, taking on enormous work loads at an age when most men would be confined to rocking chairs, and engaging in strenuous travel schedules with great enthusiasm to be anxiously engaged in building the kingdom of God” is of little interest to me (especially when you consider the history of Church Presidents being too ill in the latter years of their lives to really run the Church).[/ref] echo this important truth. After relaying a story in which he helped a friend reach his wedding in the midst of a Utah snowstorm, Elder Ashton shares,

My friend—we will call him Bill—expressed his deep gratitude with, “Thank you very much for all you did to make our wedding possible. I don’t understand

My friend—we will call him Bill—expressed his deep gratitude with, “Thank you very much for all you did to make our wedding possible. I don’t understand

why you went to all this trouble to help me. Really, I’m nobody.”

I am sure Bill meant his comment to be a most sincere compliment, but I responded to it firmly, but I hope kindly, with, “Bill, I have never helped a ‘nobody’ in my life. In the kingdom of our Heavenly Father no man is a ‘nobody.’”

…I am certain our Heavenly Father is displeased when we refer to ourselves as “nobody.” How fair are we when we classify ourselves a “nobody”? How fair are we to our families? How fair are we to our God?

We do ourselves a great injustice when we allow ourselves, through tragedy, misfortune, challenge, discouragement, or whatever the earthly situation, to so identify ourselves. No matter how or where we find ourselves, we cannot with any justification label ourselves “nobody.”

As children of God we are somebody. He will build us, mold us, and magnify us if we will but hold our heads up, our arms out, and walk with him. What a great blessing to be created in his image and know of our true potential in and through him! What a great blessing to know that in his strength we can do all things!

According to Elder Ashton, “”I am nobody” is a destructive philosophy. It is a tool of the deceiver.” Perhaps even worse is the labeling of others as “nobody”:

Sometimes mankind is prone to identify the stranger or the unknown as a nobody. Often this is done for self-convenience and an unwillingness to listen. Countless numbers today reject Joseph Smith and his message because they will not accept a 14-year-old “nobody.” Others turn away from eternal restored truths available today because they will not accept a 19-year-old elder or a 21-year-old lady missionary or a neighbor down the street because they are “nobody,” so they may suppose. There is no doubt in my mind that one of the reasons our Savior Jesus Christ was rejected and crucified was because in the eyes of the world he was blindly viewed as a “nobody,” humbly born in a manger, an advocate of such strange doctrine as “Peace on earth, good will toward men.”

Commenting on the Parable of the Prodigal Son, Elder Ashton remarks,

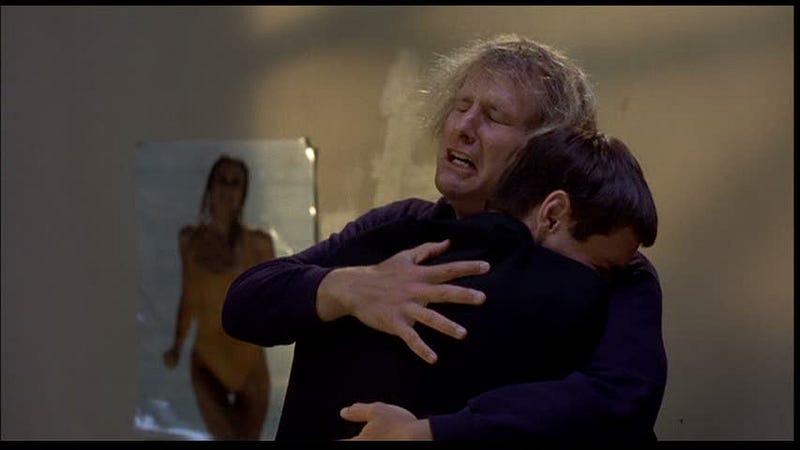

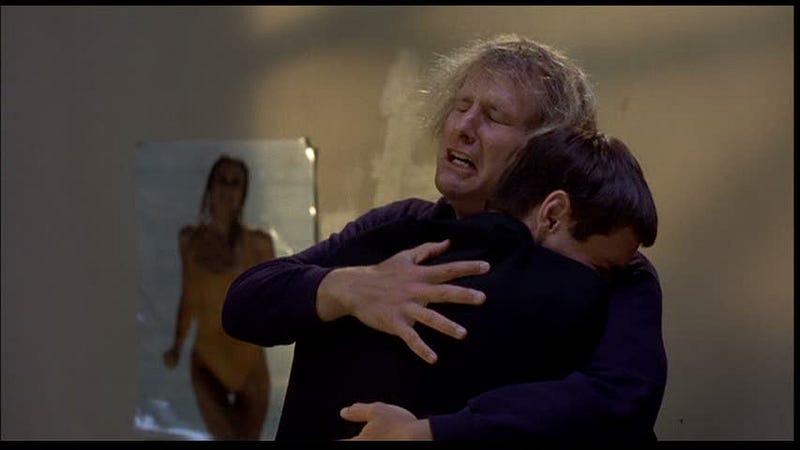

Please weigh the impact of the father’s response once more. He saw the son coming; he ran to him; he kissed him; he placed his best robe on him; he killed the fatted calf; and they made merry together. This self-declared “nobody” was his son; he was “dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.”

In the father’s joy he also taught well his older, bewildered son that he too was someone. “Son, thou art ever with me, and all that I have is thine.” Contemplate, if you will, the death—yes, even the eternal proportions—of “all that I have is thine.” I declare with all the strength I possess that we have a Heavenly Father who claims and loves all of us regardless of where our steps have taken us. You are his son and you are his daughter, and he loves you.

Do not allow yourself to be self-condemning. Avoid discouragement. Teach yourself correct principles and govern yourself with honor. Appropriately involve yourself in helping others. As we develop proper self-image in ourself and others, I promise you the “nobody” attitude will completely disappear. Ever remember wherever you are today within the sound of my voice that you are someone.

This flies in the face of some LDS interpretations in which the prodigal son “loses his inheritance”and, while “forgiven,” will likely only merit a lower kingdom. This fundamentally misunderstands the purpose of the parable. As New Testament scholar Arland Hultgren notes,

What is so striking in [the father’s] dealings with each of the sons is that he extends unconditional love prior to repentance–indeed, even apart from repentance on the part of either son. To be sure, the younger son comes home (but that does not in itself indicate repentance…), and he makes a fine speech that sounds like repentance. But the twin facts that (1) he knows he can go home and (2) the father runs and embraces him before any speech is even allowed — these two points illustrate the father’s love as unconditional prior to –indeed, apart from — repentance. And with the unconditional love is total forgiveness. In the case of the older brother, in spite of his contemptuous comments to his father and about his brother, the father assures him that all he has belongs to him still. There is no need for the son to apologize for his harsh words to the father. According to the father, the bond between them has not been severed. The attitude of the father toward his sons is not determined by their character, but his.[ref]Arland J. Hultgren, The Parables of Jesus: A Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 86.[/ref]

I wanted to address Ashton’s talk prior to that of Elder Simpson largely because I think the two work well together, but work best when read in reverse order. Elder Simpson focused on Christian living; on the lifestyle that should come about when you recognize that there are no “nobodies.” He reminds us of the Savior’s love for each and every one of us:

It has been truthfully said that the Savior is even more concerned for our success here in mortality than we ourselves are, the reason being, of course, that he has greater capacity for concern and love than do we mortals. He also has a superior knowledge of the gospel plan and man’s potential in God’s divine, eternal scheme. As stated by one prophet, God’s work and glory is achieved through our attainment of immortality and eternal life. (See Moses 1:39.)

He then lays out how we tap into this potential:

Before the foundations of this earth were laid, a glorious decision was made allowing you and me to be our brother’s keeper. By faith and service we would be able to achieve a degree of glory in the hereafter suited to our Christlike efforts and our Christlike attainments.

Adversity, heartache, bitter disappointment, grievous transgression, and disability are but a few of the obstacles that beset the inhabitants of this world. Few, if any, escape. None would have to linger in despair for long, however, if man could just bring himself to heed that one great teaching recorded in the 25th chapter of Matthew.

“For I was an hungred, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in:

“Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me.” (Matt. 25:35–36.)

Then the righteous answered, stating that not once had they found him hungry or thirsty or a stranger; and then the Savior’s classic teaching: “Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” (Matt. 25:40.)

This requires not merely monetary concerns. One of the plagues of modern American political ideologies is that both have incomplete theories of the poor and afflicted. One side simply throws money at a problem, while the other wants to rely wholly on incentives and self-reliance. Yet, Elder Simpson recognizes a more complete approach:

Every success story of the past year has been the result of special effort on the part of people who cared. They cared enough to give some time and to be sincere and compassionate; in other words, to follow the great example set by the Savior. The only joy that is comparable with the joy of the one receiving the help is the glow that seems to emanate from the one who has given so unselfishly of his time and strength to quietly help someone in need. The Savior did not seem to be so much involved in giving money. You will remember that his gifts were in the form of personal attention, in performing an administration, and in sharing the gifts of the Spirit. In fact, it was the Savior who said: “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. …” (John 14:27.) We could add to peace the gift of love, the gift of immortality, the gift of eternal life, the gift of understanding, the gift of compassion, the gift of eternal justice. All of these gifts are beyond monetary consideration and could well be our gift to someone sometime, if we weren’t “too busy.”

Every success story of the past year has been the result of special effort on the part of people who cared. They cared enough to give some time and to be sincere and compassionate; in other words, to follow the great example set by the Savior. The only joy that is comparable with the joy of the one receiving the help is the glow that seems to emanate from the one who has given so unselfishly of his time and strength to quietly help someone in need. The Savior did not seem to be so much involved in giving money. You will remember that his gifts were in the form of personal attention, in performing an administration, and in sharing the gifts of the Spirit. In fact, it was the Savior who said: “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. …” (John 14:27.) We could add to peace the gift of love, the gift of immortality, the gift of eternal life, the gift of understanding, the gift of compassion, the gift of eternal justice. All of these gifts are beyond monetary consideration and could well be our gift to someone sometime, if we weren’t “too busy.”

…No man can become “perfect in Christ” without a deep, abiding, and sincere concern for his fellow beings. This example…from James [2:15-16] cites physical needs. However, there are also emotional problems about us in every direction. Loneliness and discouragement, for example, are two of Satan’s most effective tools against us.

Simpson concludes,

If this life’s effort is to be justified, then there should be a major and continuing attempt to justify or, in other words, to conform our actions with the example of the Master. The central theme of his mortal span was purely and simply serving those about him. He fulfilled an eternal truth which should be a part of your life and my life. “And whosoever will be chief among you, let him be your servant.” (Matt. 20:27.)

If our life’s effort is to be sanctified or, in other words, ratified by the standards of eternal truth, then our actions must be in harmony with the sanctifying principles of the gospel, which most certainly includes sincere concern for others and a concerted effort to alleviate their problems.

A society is secular insofar as religious belief or belief in God is understood to be one option among others, and thus contestable (and contested). At issue here is a shift in “the conditions of belief.” As Taylor notes, the shift to secularity “in this sense” indicates “a move from a society where belief in God is unchallenged and indeed, unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option among others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace”…It is in this sense that we live in a “secular age” even if religious participation might be visible and fervent.[ref]Smith, How (Not) to Be Secular, pg. 20.[/ref]

A society is secular insofar as religious belief or belief in God is understood to be one option among others, and thus contestable (and contested). At issue here is a shift in “the conditions of belief.” As Taylor notes, the shift to secularity “in this sense” indicates “a move from a society where belief in God is unchallenged and indeed, unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option among others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace”…It is in this sense that we live in a “secular age” even if religious participation might be visible and fervent.[ref]Smith, How (Not) to Be Secular, pg. 20.[/ref] My friend—we will call him Bill—expressed his deep gratitude with, “Thank you very much for all you did to make our wedding possible. I don’t understand

My friend—we will call him Bill—expressed his deep gratitude with, “Thank you very much for all you did to make our wedding possible. I don’t understand

Every success story of the past year has been the result of special effort on the part of people who cared. They cared enough to give some time and to be sincere and compassionate; in other words, to follow the great example set by the Savior. The only joy that is comparable with the joy of the one receiving the help is the glow that seems to emanate from the one who has given so unselfishly of his time and strength to quietly help someone in need. The Savior did not seem to be so much involved in giving money. You will remember that his gifts were in the form of personal attention, in performing an administration, and in sharing the gifts of the Spirit. In fact, it was the Savior who said: “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. …” (

Every success story of the past year has been the result of special effort on the part of people who cared. They cared enough to give some time and to be sincere and compassionate; in other words, to follow the great example set by the Savior. The only joy that is comparable with the joy of the one receiving the help is the glow that seems to emanate from the one who has given so unselfishly of his time and strength to quietly help someone in need. The Savior did not seem to be so much involved in giving money. You will remember that his gifts were in the form of personal attention, in performing an administration, and in sharing the gifts of the Spirit. In fact, it was the Savior who said: “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. …” (

Recently a stake president told of his visit, with others, to a Junior Sunday School class. When the visitors entered they were made welcome, and the teacher, seeking to impress the significance of the experience for the youngsters, said to a little child on the front row, “How many important people are here today?” The child rose and began counting out loud, reaching a total of seventeen, including every person in the room. There were seventeen very important persons there that day, children and visitors!

Recently a stake president told of his visit, with others, to a Junior Sunday School class. When the visitors entered they were made welcome, and the teacher, seeking to impress the significance of the experience for the youngsters, said to a little child on the front row, “How many important people are here today?” The child rose and began counting out loud, reaching a total of seventeen, including every person in the room. There were seventeen very important persons there that day, children and visitors!