“While income trends in such groups are often referred to as growth rates of the ‘rich’ or the ‘poor’,” write the authors of a new paper,

an underappreciated point is that membership in these groups is far from stable over time. When there is mobility in the income distribution, over time some of the initially poor will rise out of the bottom 40%, while others will fall from the top 60% into the bottom 40%. The same is true at the top end, with some fortunate individuals ascending into the top 10% while others drop out of this group.

This has consequences for how to interpret trends in group average incomes. For example, the policy implications, and even the political acceptability, of a given change in average income in the top 1% of the income distribution depends crucially on whether this group of top earners consists of the same people over time, or instead whether some of the initially rich fall out of the top group and are replaced with those who were initially poorer. This distinction matters just as much at the lower end of the income distribution. For example, when evaluating interventions designed to benefit those starting out at the bottom 10% of the income distribution, it is of considerable policy importance to be able to track the same group of individuals over time, and particularly to be able to track the experiences of those who were able to increase their incomes sufficiently to rise out of the bottom 10%.[ref]This has been pointed out by others using various datasets.[/ref]

The authors, in turn,

use data from the World Income and Wealth database, which is derived from published summaries of income tax records to measure average incomes and top income shares in a sample of mostly advanced economies, as well as the World Bank’s PovcalNet database, which reports data on average incomes and summary measures of inequality based on household surveys for a large number of mostly developing countries. Some of the cross-country patterns we observe in estimates of income mobility seem quite plausible given our priors. For example, among the high-income countries, the Scandinavian countries and much of Europe show relatively high levels of income persistence, while the US, Singapore, and Taiwan rank among the countries with low levels of income persistence.

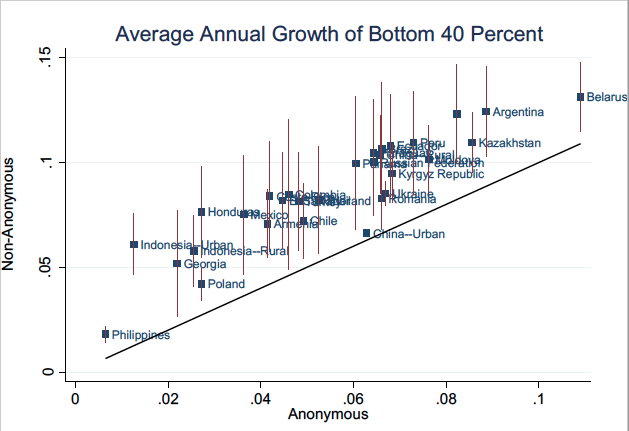

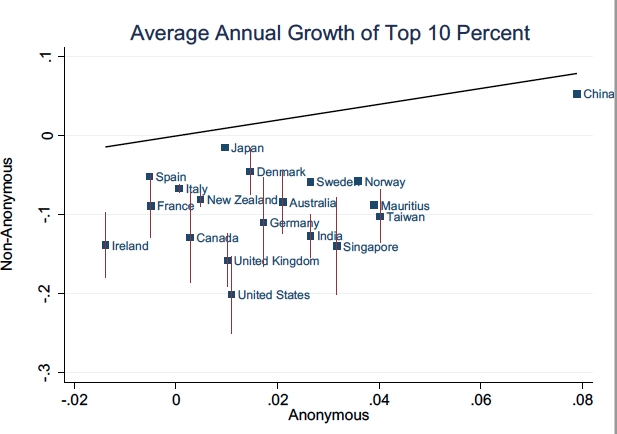

To illustrate the consequences of mobility for growth rates of group average incomes for each country in our dataset, we take the latest available ten-year period and compute the conventionally available anonymous growth rate of average incomes for the top 10% (for countries in the World Income and Wealth database) and bottom 40% (for PovcalNet countries) of the income distribution. We then compare these to estimates of the corresponding non-anonymous growth rates obtained using our approach.

…In the case of the bottom 40%, the non-anonymous growth rate is considerably higher than the corresponding anonymous growth rate (the World Bank’s measure of ‘shared prosperity’). The difference is economically significant, averaging about 3% per year. This gap reflects the fact that the non-anonymous growth rate captures the experience of those who started out in the bottom 40% but had faster-than-average growth and thus rose out of the bottom 40% by the end of the period over which the growth rate is calculated. Conversely, the anonymous growth rate is lower because it reflects the experience of those who started out above the 40th percentile but had slower-than-average growth and thus fell back into the bottom 40%. Putting these observations together, this means that by tracking shared prosperity anonymously, policymakers could inadvertently overlook the success of some initially poor individuals. Or more succinctly, those who start out poor on average grow faster than you might think based on commonly reported anonymous growth rates.

The exact opposite holds true when tracking growth at the top end of the income distribution…As a result, commonly available anonymous growth rates of top incomes exaggerate the fortunes of the rich, often by a considerable margin. Or more succinctly, those who start out rich grow more slowly than you might think based on anonymous growth rates.

Important stuff.

Princeton molecular biologist Daniel Notterman and colleagues published a new article in Pediatric titled “

Princeton molecular biologist Daniel Notterman and colleagues published a new article in Pediatric titled “

refers to family and friends who support you through difficult times, as well as neighbors and coworkers who diversify your network and expose you to new ideas. While social capital originally referred to face-to-face interaction, it now also accounts for virtual interactions online such as email or on social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

refers to family and friends who support you through difficult times, as well as neighbors and coworkers who diversify your network and expose you to new ideas. While social capital originally referred to face-to-face interaction, it now also accounts for virtual interactions online such as email or on social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56215989/467650191.0.jpg)

The FBI and the Department of Homeland Security in May warned that white supremacist groups had already carried out more attacks than any other domestic extremist group over the past 16 years and were likely to carry out more attacks over the next year, according to an

The FBI and the Department of Homeland Security in May warned that white supremacist groups had already carried out more attacks than any other domestic extremist group over the past 16 years and were likely to carry out more attacks over the next year, according to an