From a recent study:

Our bivariate analyses show that the recent cultural factors examined—communist history and religion—are, taken alone, good predictors of the Human Development Index and its components (table 1). When incorporated alongside phylogeny and geography, phylogeny ceases to be a significant predictor of HDI or any of its components, meaning recent cultural factors combined with geography can account for covariation between HDI and cultural phylogeny (table 3). Communism significantly negatively predicts HDI, income and health indices, but religion ceases to be a significant predictor except for a negative correlation between Islam and education index. These results support a significant effect of communist history on the human development of countries, comparable to the effects of geography (which remains a significant predictor of HDI and income index), and more immediately important than cultural phylogeny or religion.

…Communist history shows a significant negative correlation with the national income of the countries in our dataset. Post World War II economic growth in communist countries was modest, especially during the 1970s and 1980s, relative to non-communist European countries [92], and the centrally planned economy of communist countries has long been held by economically liberal theoreticians to hamper conventional economic growth [93–95]. Although the countries in the dataset had abandoned communism for most of the years in the dataset, the residual effect of communism appears to still be detectable. Institutional and cultural traits produced by communism and by dictatorship may continue to retard growth today, with corruption still regarded as higher in Eastern than Western Europe [96] and linked to lower national income [97]. It should also be noted, however, that many of the former communist countries (largely those in the former Soviet Union) also suffered major economic turmoil following the demise of their communist governments [98], and that this too may play a role in explaining the apparent effect of communism on income. Moreover, it must be noted that the communist countries in the sample are all Eastern European and Central Asian, and that these areas were less wealthy than Western Europe even prior to communism [92,99], and indeed Russia saw rapid economic growth following the advent of communism, although this lessened over time [92,100]. For all these reasons the results presented here must be treated with caution, and are primarily intended as a control in the context of examination of deep cultural effects on human development, not as a thoroughgoing analysis of the effects of communism on development.

Communism also shows a significant negative association with health index (i.e. normalized longevity), although only at p = 0.05 level. This confirms the stagnation and even decline of life expectancy in Europe under communism during the 1970s and 1980s, corresponding to years of low economic growth (see above), which has continued to set formerly communist countries back in terms of life expectancy until today [101,102]. The proximate causes for this low life expectancy are complex, but high alcohol consumption, smoking and poor workplace safety, as well as low quality diet and living conditions associated with lower income levels are implicated [101]. Most of the same caveats also apply here as to the economic effects of communism however, with lifespan decreasing rapidly in the former Soviet Union immediately following post-Soviet collapse [101], and lifespan having increased strongly in the Soviet Union prior to and immediately after World War II [103].

Longevity greatly increased during recent centuries in Europe in part due to generally rising living standards (and thereby nutrition [104]), with increasing health and longevity interacting with the economy in a positive feedback loop [105]. Communist history may thus have also influenced longevity via its effect on income, with income being a significant predictor of health index (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Consistent with this explanation, we find that communism is no longer a significant predictor of health index when controlling for income index.

Communism lowers human well-being. Who knew?[ref]There’s more to the study (such as Islam’s negative correlation with education), but this jumped out at me.[/ref]

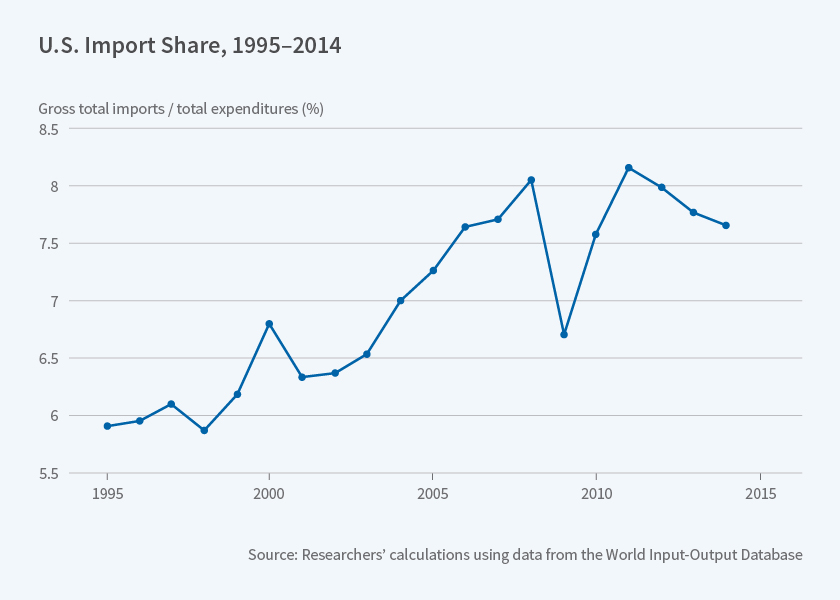

There is surprisingly little direct quantitative evidence on how the U.S. economy would react if the door were shut on trade. To find a precedent, the researchers point out that one could go back to the Embargo Act of 1807, when the United States banned trade with Great Britain and France in retaliation for their repeated violations of U.S. neutrality. GDP declined sharply, but the agrarian world during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson bears little resemblance to today’s high-tech, service-oriented economy.

There is surprisingly little direct quantitative evidence on how the U.S. economy would react if the door were shut on trade. To find a precedent, the researchers point out that one could go back to the Embargo Act of 1807, when the United States banned trade with Great Britain and France in retaliation for their repeated violations of U.S. neutrality. GDP declined sharply, but the agrarian world during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson bears little resemblance to today’s high-tech, service-oriented economy.

Putnam isn’t alone in his finding — studies in

Putnam isn’t alone in his finding — studies in

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10328631/POLICIES_AND_OUTCOMES_CHART.png)

In an

In an