A new working paper draws on Swedish manufacturing data between 1997 and 2013 to determine the effects of globalization on economic mobility. Defining globalization as “a reduction in trade costs” (pg. 22), the authors note,

Most workers land their first full-time job in their 20s and then spend 40 to 50 years in the labor market trying to earn a living. Over their careers, workers acquire new skills, which enables them to change jobs and (sometimes) occupations in order to increase job satisfaction and career earnings. It follows that a complete picture of the impact of globalization on a typical worker should take into account its impact on skill acquisition and the rate at which workers are able to secure better jobs (that is, economic mobility) (pg. 38).

The authors develop “a model of a jobs ladder in which workers gain skills on the job that qualify them for higher-paying jobs at more productive firms” (pg. 38). They explain,

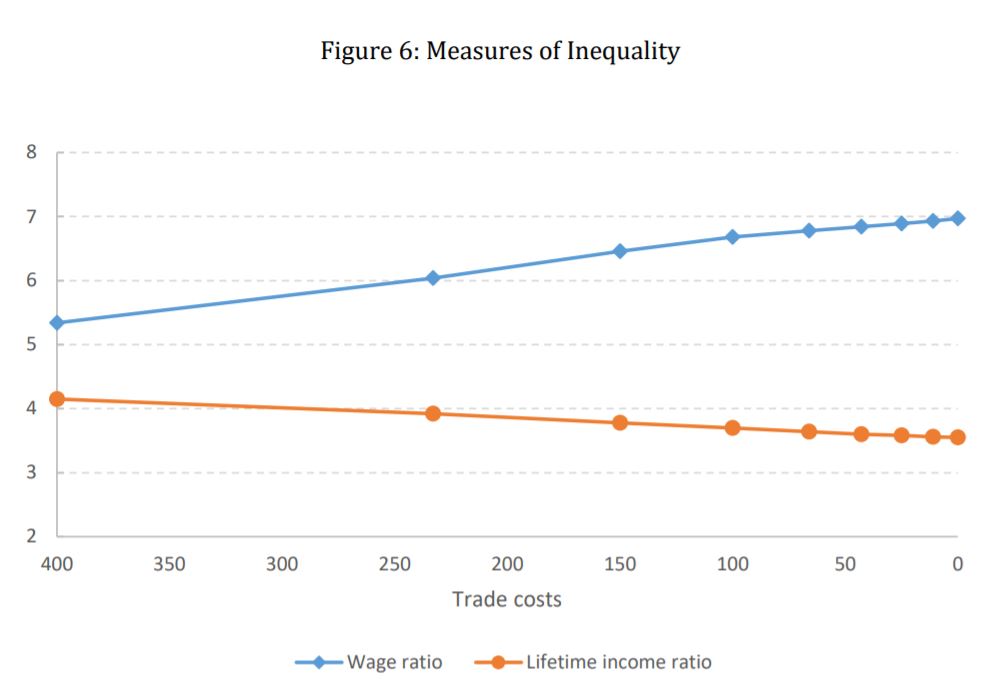

Our main finding is that when trade costs are initially high, globalization increases economic mobility through two channels. First, the reduction in trade costs leads to more international engagement by firms. As the number of exporting firms grows, the ability of workers to gain skills that reduce trade costs is enhanced. This makes it easier for workers to qualify for jobs at the top of the jobs ladder. Second, since high-productivity firms gain disproportionally from falling trade costs, globalization increases wage inequality. And, as the gaps between the wages paid by different groups of firms increase, workers become more willing to (a) incur the moving costs associated with changing jobs and (b) expend effort to keep their skills from deteriorating. As a result, upward economic mobility rises and downward economic mobility (due to demotions or terminations) falls. These changes in economic mobility reduce the differences in expected lifetime incomes forecast by workers in high-wage and low-wage jobs, resulting in the possibility that inequality in lifetime incomes might fall with globalization (even though wage inequality is rising). Even the case in which globalization increases inequality in terms of lifetime incomes, the impact is smaller than its impact on wage inequality (pg. 39).

What’s more,

Employment is reallocated from firms that pay medium wage towards the extremes, with high-wage and low-wage employment both increasing. While it is tempting to interpret this reallocation of employment as an explanation of “job polarization” as described in recent empirical work (see Goos and Manning 2007; Goos, Manning, and Salomons 2009; Autor, Katz and Kearney 2006, 2008 and Autor and Dorn 2013), we believe that would be a mistake…Our results indicate that globalization can result in a shrinking middle-class within a given occupation, with increased export opportunities resulting in more firms willing to recruit the most experienced workers by paying the highest wage; while others react to increased competition from imports by re-orienting their hiring toward inexperienced low-wage workers. These results are not driven by outsourcing. Instead, they are completely driven by the manner in which globalization alters the networks that firms use to fill their vacancies (pg. 39-40).

When trade costs are high, “globalization allows [low-wage workers] to move up the jobs ladder more quickly and, as they reach higher and higher rungs, they enjoy the enhanced benefits of the higher real wages generated by freer trade. In this case, a focus on wage inequality can be misleading in that low-wage workers do not lose as much relative to others in the labor market as would be indicated by standard analysis” (pg. 28-29). However, when trade costs are already low, “[w]age inequality rises and the rate at which workers move

out of their entry level jobs slows.” However,

the proper way to measure the effect of globalization on a worker is to examine its impact on that worker’s expected lifetime real income. That measure considers both the change in real wages and the degree of economic mobility faced by that worker. Thus, we can get a better view of how globalization affects inequality by examining the changes in expected lifetime real incomes for workers in different labor market states…Inexperienced workers only hold low-wage jobs for a portion of their lifetime, moving on to much better jobs as they gain skills. As they mature, they benefit from the higher real wages paid to medium-wage and high-wage production workers if they can gain the proper skills and land better jobs. The fact that using current wages as a proxy for lifetime earnings can lead to misleading conclusions is not a new insight. This issue is well understood and heavily researched in many sub-fields of economics; but, as far as we know, it has not received much attention from those investigating the link between globalization and inequality (pg. 29-30).

The devil is in the details.