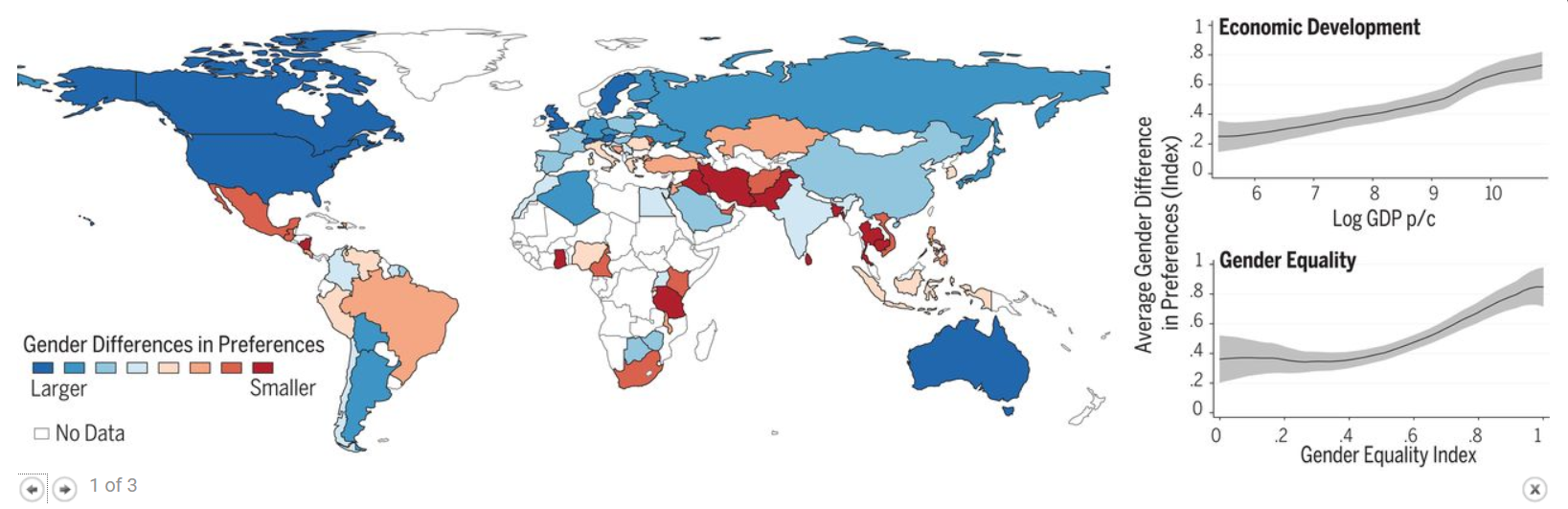

Previous research has found that the greater the gender equality, the greater the differences between genders. A brand new article in Science heaps on more evidence. Testing 80,000 individuals in 76 countries on preferences such as risk-taking, patience, altruism, positive and negative reciprocity, and trust, the authors found,

Gender differences were found to be strongly positively associated with economic development as well as gender equality. These relationships held for each preference separately as well as for a summary index of differences in all preferences jointly. Quantitatively, this summary index exhibited correlations of 0.67 (P < 0.0001) with log GDP per capita and 0.56 (P < 0.0001) with a Gender Equality Index (a joint measure of four indices of gender equality), respectively. To isolate the separate impacts of economic development and gender equality, we conducted a conditional analysis, finding a quantitatively large and statistically significant association between gender differences and log GDP per capita conditional on the Gender Equality Index, and vice versa. These findings remained robust in several validation tests, such as accounting for potential culture-specific survey response behavior, aggregation bias, and nonlinear relationships.

How do men and women differ?

On the global level, all six preferences featured significant gender differences (fig. S1): Women tended to be more prosocial and less negatively reciprocal than men, with differences in standard deviations of 0.106 for altruism (P < 0.0001), 0.064 for trust (P < 0.0001), 0.055 for positive reciprocity (P < 0.0001), and 0.129 for negative reciprocity (P < 0.0001). Turning to nonsocial preferences, women were less risk-taking by 0.168 standard deviations (P < 0.0001) and less patient by 0.050 standard deviations (P < 0.0001) (26).

The researchers conclude,

The reported evidence indicates that higher levels of economic development and gender equality are associated with stronger gender differentiation in preferences. These findings may also relate to other personality traits, such as the Big Five (34, 35) or value priorities (36). Our findings do not rule out an influence of gender-specific roles that drive gender differences in preferences. They also do not preclude a role for biological or evolutionary determinants of gender differences (37). Our results highlight, however, that theories not attributing a significant role to the social environment are incomplete (38).

In this regard, our findings point toward the critical role of availability of and equal access to material and social resources for both women and men in facilitating the independent formation and expression of gender-specific preferences across countries. As suggested by the resource hypothesis, greater availability of material resources removes the human need of subsistence, and hence provides the scope for attending to gender-specific preferences. A more egalitarian distribution of material and social resources enables women and men to independently express gender-specific preferences.