How important have high-skilled immigrants been to innovation in US history? According to a recent study,

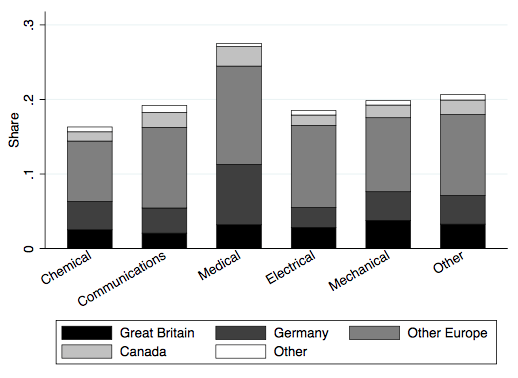

Medical inventions (e.g. surgical sutures) accounted for the largest share of immigrants, but this category produced just 1% of all US patents. However, immigrants were also active in chemicals and electricity – two sectors that had a particularly large effect on US economic growth, accounting for 13.9% and 12.6% of all US patents, respectively. Noticeably, immigrants accounted for at least 16% of patents in every area. This evidence suggests that their impact on inventive activity was widespread.

[The graph below] also shows that the majority of immigrant inventors originated from European countries, with Germans playing a particularly prominent role. This is consistent with the findings of Moser et al. (2014) who show that German-Jewish émigrés who fled the Nazi regime boosted innovation in the US chemicals industry by around 30%. Today the closest analogue to these high-impact individuals would be inventors of Indian and Chinese ethnic origin who make substantial contributions to the development of innovation clusters in areas like Silicon Valley (Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle 2010, Kerr and Lincoln 2010).

The researchers

constructed a measure of foreign-born expertise, which multiplies the share of each country’s patents granted in a given technology area between 1880 and 1940 (as a measure of proficiency) by the number of immigrants from that country in the 1940 Census (as a measure of how intensely that proficiency diffuses to the host country).

We find that technology areas with higher levels of foreign-born expertise experienced much faster patent growth between 1940 and 2000, in terms of both quality and quantity, than otherwise equivalent technology areas. Although we do not identify a causal relationship, our quantitative evidence can be used alongside qualitative evidence to highlight two areas where immigrant inventors may have acted as catalysts to economic growth: through their own inventive activity and through externalities affecting domestic inventors.

Immigrant inventors were responsible for some of the most fundamental technologies in the history of US innovation, which still influence our lives today. For example, Nikola Tesla, who was born in Serbia, worked in America on alternating current electrical systems; the Scotsman Alexander Graham Bell was instrumental to the development of the telephone from a workshop in Boston; Swedish inventor David Lindquist, while living in Yonkers, New York, assigned his patents relating to the electric elevator to the Otis Elevator Company located in Jersey City, New Jersey; and Herman Frasch, a German-born chemist, worked in Philadelphia and Cleveland on techniques which are analogous to modern fracking.

In short, the evidence suggests that “immigrant inventors were of central importance to American innovation during the 19th and 20th centuries. Although the migration of high-skilled inventors to the US involved some costs, immigrant inventors contributed heavily to new idea creation, through both their own work and collaboration with domestic inventors. Our evidence aligns with the view that growth in an economy is determined by its ablest innovators, regardless of national origin. The movement of high-skilled individuals across national borders therefore appears to have aided the development of the United States as an innovation hub.”

This post is part of the

This post is part of the