Economist Michael Clemens has an excellent article in Vox discussing some of his most recent research on immigration and in turn responds to Harvard’s George Borjas, the most prominent anti-immigration economist around:

Do immigrants from poor countries hurt native workers? It’s a perpetual question for policymakers and politicians. That the answer is a resounding “Yes!” was a central assertion of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. When a study by an economist at Harvard University recently found that a famous influx of Cuban immigrants into Miami dramatically reduced the wages of native workers, immigration critics argued that the debate was settled.

…But there’s a problem. The study is controversial, and its finding — that the Cuban refugees caused a large, statistically unmistakable fall in Miami wages — may be simply spurious. This matters because what happened in Miami is the one historical event that has most shaped how economists view immigration.

In his article, Borjas claimed to debunk an earlier study by another eminent economist, David Card, of UC Berkeley, analyzing the arrival of the Cubans in Miami. The episode offers a textbook case of how different economists can reach sharply conflicting conclusions from exactly the same data.

Yet this is not an “on the one hand, on the other” story: My own analysis suggests that Borjas has not proved his case. Spend a few minutes digging into the data with me, and it will become apparent that the data simply does not allow us to conclude that those Cubans caused a fall in Miami wages, even for low-skill workers.

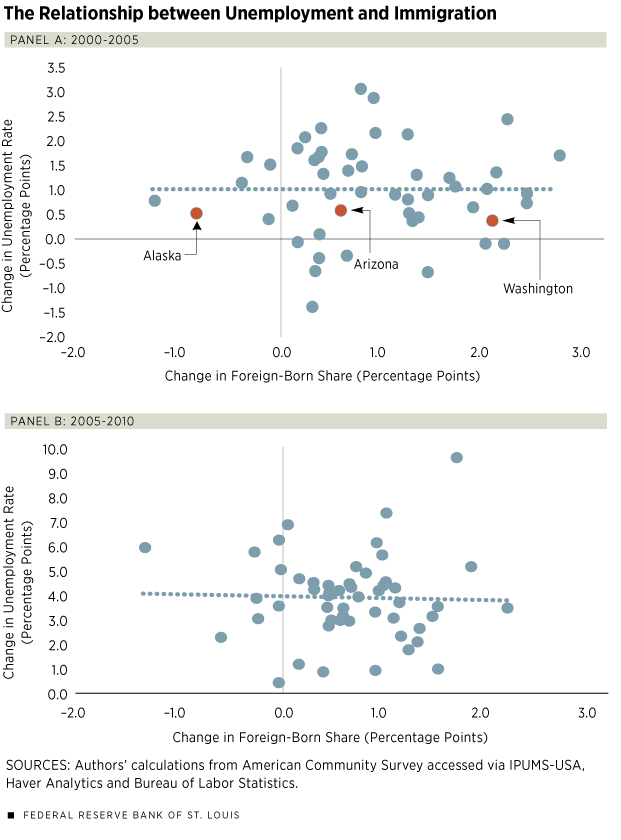

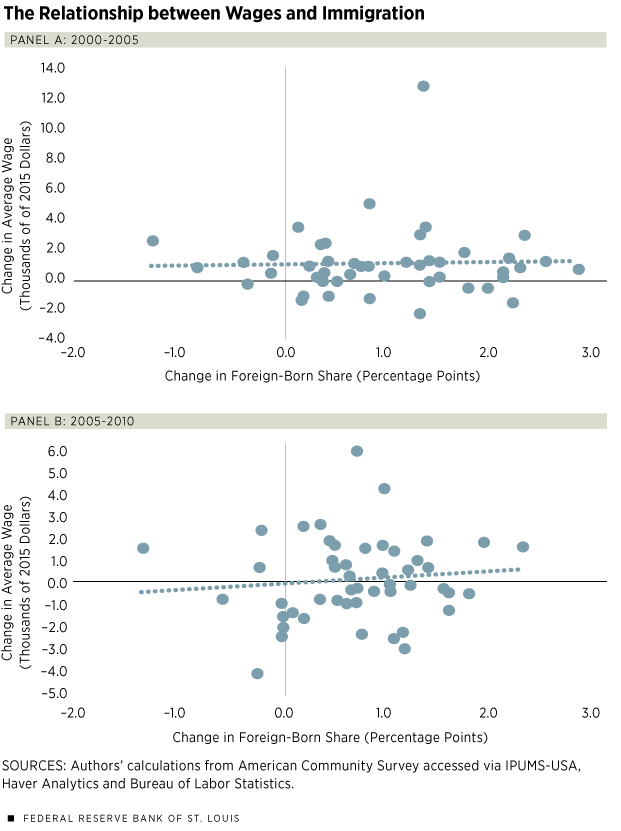

An influential 1990 study found “no difference in wage or employment trends between Miami — which had just been flooded with new low-skill workers — and other cities” following the arrival of 125,000 Cuban immigrants.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8733367/fig1muriel.png)

Two new studies reexamined the 1990 study. “Borjas, instead, focuses on workers who did not finish high school — and claimed that the Boatlift caused the wages of those workers, those truly at the bottom of the ladder, to collapse. The other new study (ungated here), by economists Giovanni Peri and Vasil Yasenov, of the UC Davis and UC Berkeley, reconfirms Card’s original result: It cannot detect an effect of the boatlift on Miami wages, even among workers who did not finish high school.” Clemens suggests looking at

certain subgroups that may have competed more directly with the newly-arrived Cubans. For example, the Mariel migrants were mostly men. They were Hispanic. Many of them were prime-age workers (age 25 to 59). So we should look separately at what happened to wages for each of those groups of low-skill workers who might compete with the immigrants more directly: men only, non-Cuban Hispanics only, prime-age workers only…Here again, if anything, wages rose for each of these groups of low-skill workers after 1980, relative to their previous trend. There isn’t any dip in wages to explain. And, again, the same is true if you compare wage trends in Miami to trends in other, similar cities. Peri and Yasenov showed that there is still no dip in wages even when you divide up low-skill workers by whether or not they finished high school. About half of the Mariel migrants had finished high school, and the other half hadn’t. So you might expect negative wage effects on both groups of workers in Miami. Here is what the wage trends look like for those two groups.

The wages of Miami workers with high school degrees (and no more than that) jump up right after the Mariel boatlift, relative to prior trends. The wages of those with less than a high school education appear to dip slightly, for a couple of years, although this is barely distinguishable amid the statistical noise. And these same inflation-adjusted wages were also falling in many other cities that didn’t receive a wave of immigrants, so it’s not possible to say with statistical confidence whether that brief dip on the right is real. It might have been — but economists can’t be sure. The rise on the left, in contrast, is certainly statistically significant, even relative to corresponding wage trends in other cities.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8733387/Mariel.newfig2.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8733417/Mariel.newfig3.png)

So how did Borjas come to different conclusions? He “starts with the full sample of workers of high school or less — then removes women, and Hispanics, and workers who aren’t prime age (that is, he tosses out those who are 19 to 24, and 60 to 65). And then he removes workers who have a high school degree. In all, that means throwing out the data for 91 percent of low-skill workers in Miami in the years where Borjas finds the largest wage effect. It leaves a tiny sample, just 17 workers per year.” Borjas’ conclusions involve a lot of statistical noise and, as Clemens notes, “if we’re willing to take low-skill workers in Miami and hand-pick small subsets of them, we can always find small groups of workers whose wages rose during a particular period, and other groups whose wages fell. But at some point we’re learning more about statistical artifacts than about real-world events.”

But there is another factor at work:

it turns out that the CPS sample includes vastly more black workers in the data used for the Borjas study after the boatlift than before it.

Because black men earned less than others, this change would necessarily have the effect of exaggerating the wage decline measured by Borjas. The change in the black fraction of the sample is too big and long-lasting to be explained by random error. (This is my own contribution to the debate. I explore this problem in a new research paper that I co-authored with Jennifer Hunt, a professor of economics at Rutgers University.)

Around 1980, the same time as the Boatlift, two things happened that would bring a lot more low-wage black men into the survey samples. First, there was a simultaneous arrival of large numbers of very low-income immigrants from Haiti without high school degrees: that is, non-Hispanic black men who earn much less than US black workers but cannot be distinguished from US black workers in the survey data. Nearly all hadn’t finished high school.

That meant not just that Miami suddenly had far more black men with less than high school after 1980, but also that those black men had much lower earnings. Second, the Census Bureau, which ran the CPS surveys, improved its survey methods around 1980 to cover more low-skill black men due to political pressure after research revealed that many low-income black men simply weren’t being counted.

You can see what happened in the graph below, which has a point for each year’s group of non-Hispanic men with less than high school, in the data used by Borjas (ages 25 to 59). The horizontal axis is the fraction of the men in the sample who are black. The vertical axis is the average wage in the sample. Because black men in Miami at this skill level earned much less than non-blacks, it’s no surprise that the more black men are covered by each year’s sample, the lower the average wage.

But here’s the critical problem: The fraction of black workers in this sample increased dramatically between the years just before the boatlift (in red) and the years just after the boatlift (in blue). That demographic shift would make the average wage in this group appear to fall right after the boatlift, even if no one’s wages actually changed in any subpopulation. What changed was who was included in the sample.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8733469/Mariel.newfig5.png)

“When the statistical results in the Borjas study are adjusted to allow for changing black composition of the sample in each city,” Clemens continues, “the result becomes fragile. In the dataset Borjas focuses on, the result suddenly depends on which set of cities one chooses to compare Miami to. And in the other, larger CPS dataset that covers the same period, there is no longer a statistically significant dip in wages at all.” And once “you’ve discarded women, and Hispanics, and workers under 25, and workers over 59, and anyone who finished high school— and blacks, you’ve thrown away 98 percent of the data on low-skill workers in Miami. There are only four people left in each year’s survey, on average, during the years that the Borjas study finds the largest effect. With samples that small, the statistical confidence interval (represented by the dotted lines) is huge, meaning we can’t infer anything general from the results. We can’t distinguish large declines in wages from large rises in wages — at least until several years after the boatlift happened, and those can’t be plausibly attributed to the boatlift.”

In conclusion, “[t]here is no clear evidence that wages fell (or that unemployment rose) among the least-skilled workers in Miami, even after a sudden refugee wave sharply raised the size of that workforce. This does not by any means imply that large waves of low-skill immigration could not displace any native workers, especially in the short term, in other times and places. But politicians’ pronouncements that immigrants necessarily do harm native workers must grapple with the evidence from real-world experiences to the contrary.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8733367/fig1muriel.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8733387/Mariel.newfig2.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8733417/Mariel.newfig3.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8733469/Mariel.newfig5.png)