For some reason, I allowed Nathaniel to drag me into this 14-year scheme of reading a new General Conference session every week (you can check his post for the details). My first reaction was a big nope. Quite honestly, General Conference bores me. I don’t find it particularly edifying and frankly find the style and content of most General Authority talks to be lacking (to put it kindly). So the idea of reading multiple talks a week and then writing about them couldn’t have been less appealing.

For some reason, I allowed Nathaniel to drag me into this 14-year scheme of reading a new General Conference session every week (you can check his post for the details). My first reaction was a big nope. Quite honestly, General Conference bores me. I don’t find it particularly edifying and frankly find the style and content of most General Authority talks to be lacking (to put it kindly). So the idea of reading multiple talks a week and then writing about them couldn’t have been less appealing.

And yet…

As I thought about it, the project seemed more and more worthwhile. I would become truly familiar with the teachings and trends of modern Mormonism. I would understand more fully what my parents’ generation grew up with. Furthermore, I would be taking seriously the words of leaders I sustain as prophets, seers, and revelators.

The April 1971 morning session was a good place to start. It combined the things that I both love and hate about General Conference. The first two talks were less than stellar. Joseph Fielding Smith’s talk was (what would now be) a typical, unremarkable rundown of basic Mormon beliefs. His outline could be straight out of a manual. The talk has virtually no scriptural references or historical sources. While this probably shouldn’t bother me, it does. Mormon theology has evolved and I don’t think many members or leaders are aware of its evolution, despite the claim of “continuing revelation.” Granted, this was 1971. The New Mormon History was just starting to gain momentum (The Mormon Experience hadn’t even been published). Despite these misgivings, I did like this line: “…The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints [is] the custodian and dispenser of [the gospel’s] saving truths…” Reminded me of Terryl & Fiona Givens’ claim in The Crucible of Doubt that members of the LDS Church are custodians of the temple.

Spencer W. Kimball’s talk was annoyingly alarmist, though intriguing from a historical view. Kimball engages in some inflammatory anti-gay rhetoric, being two years after the Stonewall riots. But considering the 1970s was a transformative decade for the LGBT community, it is interesting to see how some Church leaders were responding to the trends around them. Nonetheless, the “perversion” of homosexuality is not the main topic, but fits snuggly into Kimball’s apocalyptic rhetoric and worldview: “We are living in the last days, and they are precarious and frightening. The shadows are deepening, and the night creeps in to envelop us.” According to Kimball, the “world is now much the same as it was in the days of the Nephite prophet who said: “… if it were not for the prayers of the righteous … ye would even now be visited with utter destruction. …” (Alma 10:22.)” Our world is “sinking into depths of corruption. Every sin mentioned by Paul is now rampant in our society.” The “eccentricities and disobedience” of the youth are “laid at the feet of those parents who gave them an example of disobeying both government and God’s laws.” Among these sweeping statements, Kimball makes the following claim without a hint of irony: “Many voices, loud and harsh, come from among educators, business and professional men, sociologists, psychologists, authors, movie actors, legislators, judges, and others, even some of the clergy, who, because they have learned a little about something, seem to think they know all about everything.” Since I think the evidence is in favor of the world getting better overall, I found little to be salvaged from this talk.

However, Marvin J. Ashton’s talk struck home for me. With President Nixon declaring a “war on drugs” in June of that year, it is noteworthy that drug addiction plays a prominent role in Ashton’s talk. Yet, it isn’t the addiction or drug use that is Ashton target, but the reasons for it:

If we as parents and friends advise our youth that drugs are bad, evil, and immoral, and yet we do not try to understand why our youth turn to this evil substitute for reality, then the drugs themselves become the issue and not the symptom of the greater issue of unhappiness. We need to know why our loved ones want to run from their present life to the unknown yet dangerous life of addiction. What causes a strong, lovely, vibrant young person to allow a chemical to control his or her behavior? What is there at home, school, work, or church that is so uncomfortable that an escape seems necessary? If we were not faced with the evils of marijuana, LSD, speed, and heroin, we would be faced with some other type of escape mechanism, because some of us as brothers, sisters, parents, friends, and teachers have not yet been able to reach our youth in such a way as to give them the confidence and love they seek. Some of us are not providing the stability in the home, the respect, and the care that every person needs. They need more than Church upbringing—they need a loving home life.

Ashton’s approach recognizes the lack of human connection behind addiction. Without using the term, his description acknowledges drug use as a shame-based behavior: “May I reiterate that while drugs are a most serious problem, and while the Church is a flexible instrument in the Lord’s hands, we must not be diverted from our eternal and most effective course by problems that, though serious, are only symptoms of greater ills” (italics mine). The way to address these “greater ills” is to “strengthen their homes and personal lives through warm, loving reeducation around basic gospel principles.” Instead of responding undesirable behaviors with shame, anger, and fear, “it is imperative that there be love, understanding, and acceptance in the home so our youth can learn that only steadfast pursuit of God’s ways will bring a rich, happy life.” And though many “who are part of the drug scene tend to adopt unusual dress, hair styles, and other mannerisms which set them apart…we do only harm by rejecting them from our meetings and general fellowship.”[ref]Only if they “become offensive or unacceptable by reason of extreme behavior” should we exclude them.[/ref] He offers credible advice to parents:

Parents, let’s make certain our youth are not continually exposed to the idea that the stresses of daily life require chemical relief. Factual information about drugs should be constantly stressed rather than attempts to frighten or shame. We must try to rear our children so that they are neither deprived of affection nor spoiled. We must give our children responsibilities according to their capabilities and never overprotect them from the difficulties they will encounter. As sure as some adults—mothers and fathers—continue to sow the wind, they will reap the tornado. Let us more firmly entrench ourselves in the true purposes of family life and sow oneness and reap joy.

And what of those who feel they are “failing in the home” because of their wayward children?: “I believe we start to fail in the home when we give up on each other. We have not failed until we have quit trying. As long as we are working diligently with love, patience, and long-suffering, despite the odds or the apparent lack of progress, we are not classified as failures in the home. We only start to fail when we give up on a son, daughter, mother, or father.”

The contrast between Ashton and Kimball demonstrates that if apostles can see and address the world differently, so can local members.

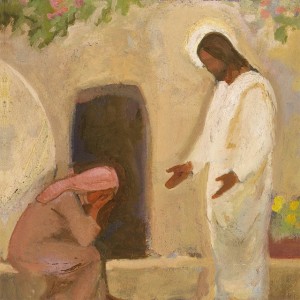

Finally, Ezra Taft Benson offers a healthy, edifying testimony of our eternal nature, the Resurrection, and the need for an eternal perspective. It was an excellent follow-up to Ashton’s talk, reminding us of our inner divinity and potential: “As eternal beings, we each have in us a spark of divinity. And, as one who has traveled over much of this world, on both sides of the iron curtain, I am convinced that our Father’s children are essentially good. They want to live in peace, they want to be good neighbors, they love their homes and their families, they want to improve their standards of living, they want to do what is right, they are essentially good. And I know that God loves them.” But all these virtuous desires do not end here because of the Savior’s resurrection: “Yes, there is the ever expectancy of death, but in reality there is no death—no permanent parting. The resurrection is a reality.” Peace between peoples, good neighbors, loving homes and families will not end. They will continue because death has been conquered. I wholeheartedly agree with Benson’s declaration: “There is nothing in history to equal that dramatic announcement. “He is not here, but is risen.””

Finally, Ezra Taft Benson offers a healthy, edifying testimony of our eternal nature, the Resurrection, and the need for an eternal perspective. It was an excellent follow-up to Ashton’s talk, reminding us of our inner divinity and potential: “As eternal beings, we each have in us a spark of divinity. And, as one who has traveled over much of this world, on both sides of the iron curtain, I am convinced that our Father’s children are essentially good. They want to live in peace, they want to be good neighbors, they love their homes and their families, they want to improve their standards of living, they want to do what is right, they are essentially good. And I know that God loves them.” But all these virtuous desires do not end here because of the Savior’s resurrection: “Yes, there is the ever expectancy of death, but in reality there is no death—no permanent parting. The resurrection is a reality.” Peace between peoples, good neighbors, loving homes and families will not end. They will continue because death has been conquered. I wholeheartedly agree with Benson’s declaration: “There is nothing in history to equal that dramatic announcement. “He is not here, but is risen.””

I take the good with the bad of General Conference. I’m excited to do so each week.

—-

Here are the other folks participating in this grand scheme who have also written blog posts responding to the Saturday Morning session of the April 1971 General Conference. (If any of the links don’t work, try back later. They are all coming online during the day.)

- The Voices of the Prophets (G at Junior Ganymede)

- LDS Conference April 1971- Hippies, Drugs, and Failure in the Home (J. Max Wilson at Sixteen Small Stones)

- Custodian and Dispenser of Saving Truth (Daniel Ortner at Symphony of Dissent)

- Voices of the Past, of the Present, of the Future (John Hancock at Good Report)

- April 1971: Nothing New Here – Just Same Ol’ Mormonism (Ralph Hancock at Soul and City)

- Our individual battles to overcome our worlds (Michelle L at Mormon Women)

- Beginnings and Endings (Nathaniel Givens here at Difficult Run)

This is an astute if cheeky recounting of and commentary on these talks situated as they are in the 70s. I always thought that Marvin Ashton was a voice of reason, and I love the fact that you argued that if there can be variance in GA talks about similar topics, then variance should be tolerated if not celebrated among Mormons. I’ve long argued myself that it’s time to explode the notion of what a “Mormon” is to include all the adjectives: neo-conservative, liberal, lapsed, “Jack,” secular and my favorite “ethnic Mormon.” Cory, the redoutable heroin of Maureen Whipple’s “The Giant Joshua” memorably says that there might come a time when Mormons could disagree among themselves and with the leadership but that neither the mid-19thC, nor the pioneer settlement of St. George–the novel’s setting–were the time or the place. The time is long overdo.