Asking for evidence of police brutality doesn’t make you blindly pro-cop. Being skeptical of the officer’s POV doesn’t make you blindly anti-cop.

I’ve seen people defend Officer Sean Groubert shooting Levar Jones even after Groubert was fired and charged with a felony count of assault and battery (he has since plead guilty). I’ve had arguments with people who claim the video of Officer Michael Slager repeatedly shooting Walter Scott in the back was deceptively edited, even though Slager has since been fired and charged with murder and obstruction of justice. There are people for whom no amount of evidence is enough.

So when someone says “We weren’t there. We don’t know what happened. We shouldn’t jump to conclusions,” I’m sure I’m not the only one who feels weary and angry. I get frustrated because so many times those statements are insincere; so many times, when it comes down to it, the person patiently calling for objectivity and evidence doesn’t actually care about evidence at all. He says “Give the investigation time,” but he means “no matter what surfaces, I’ll assume the officer was in the right. No matter the injustice, I’ll believe the dead deserved it.”

But I need to be careful about my assumptions. On the surface there’s no way to tell the difference between the person who is really just going to side with the LEO no matter what and the person who genuinely cares about clear thinking and due process. It’s unfair to assume anyone calling for more information falls into the former category.

It’s also unhelpful. I want more people to consider the possibility that serious systemic problems are at play here; accusing people of bigotry just for asking for evidence isn’t likely to start a thoughtful conversation.[ref]When I think about a lot of the problems in our current political climate, shutting down tricky conversations with accusations of bigotry seems to be a recurring theme.[/ref]

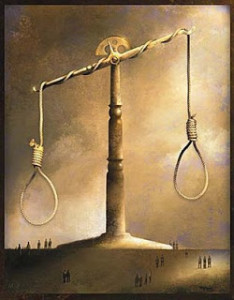

The principles of (1) innocent until proven guilty and (2) proof beyond a reasonable doubt inevitably mean truly guilty people will go free. Our justice system is (supposed to be) designed to err on the side of freeing the guilty rather than imprisoning the innocent. In fact, jurors are given explicit instructions to this end: if they’re presented with multiple theories about how a crime happened, they are supposed to pick whichever is most reasonable. But if there is more than one reasonable theory, they are supposed to pick the reasonable theory that finds the defendant innocent.

In the case of an officer-involved shooting, that means if there’s a reasonable chance the officer acted in self-defense and there’s a reasonable chance he did not, the jury is supposed to assume it was self-defense. Given how often LEOs do have to fear for their lives[ref]As I write, I’m reading about the shootings in Dallas last night that have left several officers dead. We can both call for LEOs to be held to high standards and acknowledge and respect the dangers their jobs entail.[/ref]–and given that the dead can’t talk–this means an officer can claim self-defense and, absent extremely explicit evidence to the contrary[ref]And I don’t just mean video evidence that an LEO hurt or killed a citizen. I mean video evidence that the LEO hurt or killed a citizen and could not have reasonably believed the citizen was a threat.[/ref], the jury will assume that’s the truth.

I would think that’s what we’d all want for ourselves if we were accused of a crime. We’d want the evidence to have to show beyond a reasonable doubt that we did the deed before we could be found guilty. Of course we would.

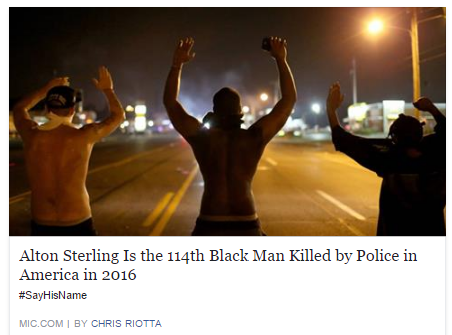

I would also expect we’d all want the right to defend ourselves in dangerous situations. That’s why I think it really undermines the Black Lives Matter movement and its allies when people fail to distinguish between LEO self-defense vs LEO abuse of power. For example, I’ve seen a few posts along these lines:

This article references a database put together by The Washington Post to track officer-involved shooting deaths. But the stat is for everyone shot and killed by police, whether those citizens were a danger to the officers’ lives or not. While I think it’s important to track that kind of information, I also think it’s misleading to use it in the context of police brutality.

Police brutality is unwarranted LEO aggression and violence, but not all LEO aggression is unwarranted. Good cops acting in self-defense shouldn’t be lumped in with corrupt cops abusing their power or even with incompetent cops dangerously overreacting. And victims of police brutality shouldn’t be lumped in with people killed attempting to commit violence against others. Equivocations like these are part of the reason so many hesitate to condemn a given shooting, instead asking for more information. It’s “the Social Justice Warrior who cried ‘police brutality,'” and many people aren’t interested in more accusations until all the facts are in.

The problem with that, though, is that there are a lot of cases in which the facts are never all in.

The Walter Scott case is a great example of what so many people now fear and expect: Officer Slager is being charged not just with murder but also with obstruction of justice because, after repeatedly shooting Scott in the back, Slager told investigators that Scott had been advancing toward Slager with a taser. It was only when a citizen turned over a cell phone video that it became clear Scott had actually been running away from Slager. If the citizen hadn’t come forward with the video, what are the odds Slager would’ve been charged with anything?

Similarly, when multiple deputies beat Derrick Price, two of them later submitted falsified reports claiming Price had resisted arrest. According to court documents, security footage later revealed that “Price was compliant and immobilized during the entire time of the beating.” The two deputies subsequently plead guilty to deprivation of rights, but if there had been no security footage it’s unlikely their false reports would’ve been discovered.

These are examples of officers being willfully deceptive, but I expect there are plenty of situations where an officer recounts events sincerely and still gets them wrong. Eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable; I see no reason this would apply less to officers than anyone else.

For example, Officer Groubert suggested he shot Levar Jones because he perceived Jones to be a threat, claiming Jones “dove” into his van. Groubert may very well have believed that, but his own dash cam footage shows Jones simply reach into the van directly after Groubert asked for Jones’ license and registration. That footage contributed to Groubert being fired and charged, but if there had been no dash cam footage, would citizen safety still depend on Officer Groubert’s judgement?

Officer Timothy Runnels tased teen Bryce Masters until Masters went into cardiac arrest. Police later claimed Masters had been uncooperative during the stop, but dash cam footage shows Masters only asking whether he was under arrest before Runnels tased him and dropped him face down on the pavement. Runnels has since been fired and plead guilty to civil rights violations, but if there had been no dash cam footage?

Some people say these cases show our system does work because–given sufficient evidence–officers are charged with crimes. But I hope you can see how problematic this is. These cases are rare in that there was clear-cut video footage. How often do officers overreact, like Goubert did, or willfully try to deceive, like Slager did, with no video evidence to catch them? Perhaps it almost never occurs, and the exceedlingly rare times when it does occur happen to be disproportionately caught on video.

But I doubt it. A lot of people doubt it. Each time an LEO is caught not only unlawfully hurting citizens but also trying to cover it up, it greatly erodes public trust. And each time seemingly damning evidence proves insufficient to even indict an officer, it greatly erodes public trust. Each time there’s no major repercussion for anyone from the LEO himself to his superiors for, at best, grave errors in judgement, it greatly erodes public trust.

And once the public no longer trusts the system, cautioning people to reserve judgement until all the facts are in starts to sound a little too much like telling people to never judge an officer-involved death at all. In most cases all we can do is wait for one side of the story, and we already know what that side will say. It’s “the LEO who cried ‘self-defense.'”

So, while I understand people calling for calm and for evidence–a good approach not just here but in general–I also understand a lot of people feeling completely disillusioned and distrusting of the evidence-gathering process. I understand why having a jury decide an officer shouldn’t be indicted or isn’t guilty doesn’t necessarily convince the public the officer actually isn’t guilty.

People seem to believe this level of suspicion can only stem from a general anti-cop sentiment, but I don’t agree. Given the known cases of officers abusing power and then lying about it, it’s reasonable for people who respect the profession in general to still have major concerns about this issue specifically. I don’t agree with Jon Stewart on everything but I thought he was spot on here:

I don’t pretend to have a simple solution to all of this. I want to live in a society where people of color and LEOs are safe. I want us to respect the principles of “innocent until proven guilty” and “proof beyond a reasonable doubt.” I want law enforcement agencies to responsibly police their own ranks. It doesn’t seem like any of that is happening right now.

I’m not sure what to do, but I am sure that assigning the worst motivations to the other side doesn’t help anything. We may not be able to fix everything quickly, but we can at least try to understand where people are coming from.