There’s a general assumption among most Americans that democracy is a good thing and that, as a general rule, more democracy is better. With the single exception that we ought to have a Bill of Rights to carve out protections so that the majority cannot persecute the minority, reforms like direct election of Senators (before the adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913, state legislatures elected national Senators), direct involvement via ballot initiatives, and even reform of the Electoral College to apportion votes equitably with respect to population all seem to strike most people as more or less common sensical. The same general attitude is applied internationally as well, which is why so many Americans were initially supportive of the Arab Spring revolutions that swept the Middle East.

I think this is all wrong. Democracy, in my mind, is overrated. And for clarity, “democracy” means to me “rule by the majority” or even just “rule by the people”.

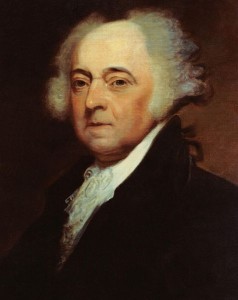

Let’s start at the beginning with the American Revolution. There’s a widespread urban legend that 1/3 of Americans supported the Revolution, 1/3 were neutral, and 1/3 opposed it. The problem with this view is that it’s not actually accurate. It stems from a letter by John Adams written in 1813 that was actually about American opinions of the French Revolution, although it has been mistakenly quoted by historians dating back to the early 1900’s. The best explanation I’ve found for this issue comes from the Journal of the American Revolution, which addressed the issue directly. According to that piece, no one really knows what the actual breakdown for support of the American Revolution was. In addition to the absence of statistical polling at the time, the issue is complicated by the fact that the American population was growing very rapidly. However (citing the Journal of the American Revolution again), historians like Robert Calhoon estimate that between 40% and 45% of the free population (so African American slaves are not included) or “at most no more than a bare majority” supported the Revolution. So the 1/3-1/3-1/3 quote is erroneous, but the idea that the Revolution was supported by a minority of Americans is reasonable.

This is a controversial claim. Another organization that weighed in on this issue is the Independent Institute, a conservative/libertarian think tank. William F. Marina wrote a piece for them denouncing the “minority myth” as a malicious lie to support elitism and citing “the obvious delight that these writers take, which is, indeed, a major reason they cite it, in the notion that it is a minority that often knows best.” Despite Marina’s foreceful defense of the view that the majority of Americans supported the Revolution, however, the Founders themselves seemed less clear about it. Writing to a friend in 1813, John Adams responded to his friend Thomas McKean’s assertion that the overwhelming majority of Americans had supported the Revolution, Adams demurred. He cited the strength of the Loyalist cause and then wrote (again, Journal of the American Revolution): “Upon the whole, if we allow two thirds of the people to have been with us in the revolution, is not the allowance ample?”

So we should take two things from this. The first is that we don’t really know if the majority of Americans supported the Revolution or not, and neither did (at least some of) the Founders. The second is that, to this day, that assertion is hotly contested. Why? Because of an idea that the American political system is founded on the “will of the people” and that–if the Founders did not follow the will of the people–they were “a pretty slippery and hypocritical bunch”, as Marina put it.

I have a different perspective. I think that there is an important distinction between (to use my own terminology) the consent of the governed and the intent of the governed. And I think that when most Americans envision “democracy” they are implicitly assuming that government ought to reflect the intent of the governed. For example, I think that most Americans believe that the purpose of elected representatives is basically practical. We can’t ask Americans for their opinion on every single law, and so we elect representatives, and their job is to go and act as a simple stand-in for their constituents. That is why we passed the 17th Amendment: so that Senators would directly represent their constituents, as opposed to having the state legislature exist as an intermediary. Based on this idea (the intent theory of representative government), not only do legislatures act as stand-ins for their constituents, but the rest of government (the executive and judicial branches) are also simply practical necessities. We have a President because, especially in times of crisis, we need a single person who can act decisively and unambiguously. We have a judicial system purely as a kind of expert legal consultant, although in recent years there has been increasingly a theory that even the Supreme Court ought to reflect the changing mores and attitudes of society. In short: the intent theory is the idea that the entire apparatus of the American political system is an elaborate attempt to enact the will of the American people. In this view, the government (and everyone who works there) is essentially a passive filter that processes the intent of Americans into official law and action.

I believe this is entirely wrong.

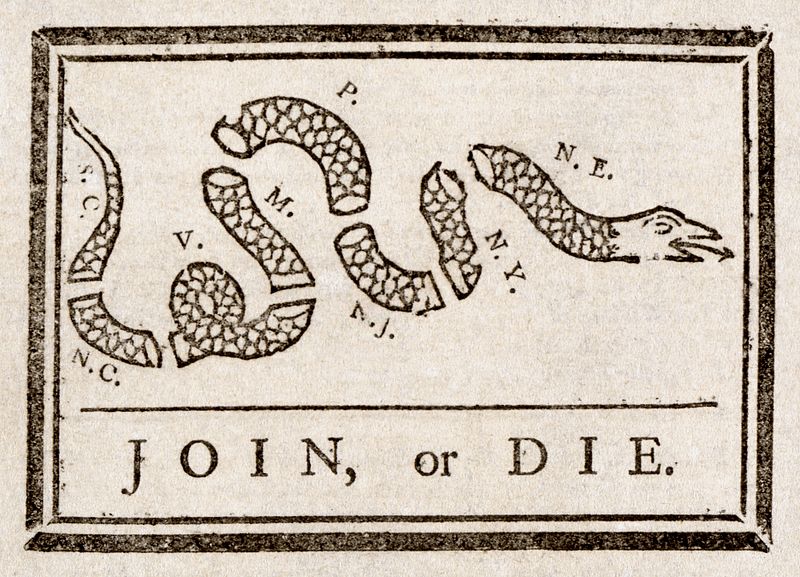

First of all, I don’t believe that was the intent of the Founders in creating the system. This is clear from both their actions before and during the Revolution and also from the system that they created. In terms of actions: they acted proactively without waiting for the will of the majority to be clear. John Adams’ letter reflects this. It’s obvious that the will of the people was crucial to their view of governmental legitimacy, but it didn’t serve as the source of government action. In simple terms, the Founders asked for permission from the American people, but didn’t wait for instructions. That’s fundamentally incompatible with the idea that the government merely enacts the intent of the American people. In terms of political structure: the design of the American political system laid down in the Constitution is incompatible with the idea that it is merely a passive filter. After all, the 17th Amendment wasn’t passed until the 20th century. The original intent of the Founders was to intentionally create a layer between national and state government, and have that layer remove the American people a step or two from the process. Since there’s no practical reason for that design decision (it wouldn’t have been significantly more difficult to have popular election for the Senate), it shows that the Founders deliberately chose a less-democratic political system.

Why? Because the Founders were not fools.

The most influential writer on this topic that I’ve read is the modern libertarian scholar Bryan Caplan who wrote The Myth of the Rational Voter. Caplan’s main point, in this book, was to document specific systematic biases common to American voters that lead to poor economic policies. But, along the way, he also pointed out that an important advantage of voter ignorance is that it leaves wiggle room for their representatives to make better decisions that would be unpopular if (biased) American voters knew exactly what was going.

Now I expect that this line of argument is going to raise all kinds of red flags with people, and it should. But the fundamental reality is that elitism has some things going for it. Who do you want to do analysis about global warming, PhD scientists or the man on the street? Who do you want to perform surgery on your kid, a trained and accredited surgeon or a randomly selected poll respondent? Then elitism has a role to play in our society. The government makes policies based on or impacting scientific, strategic, economic, and other matters where expertise is absolutely essential if you want good policies. Then elitism has a role to play in our government.

Now I expect that this line of argument is going to raise all kinds of red flags with people, and it should. But the fundamental reality is that elitism has some things going for it. Who do you want to do analysis about global warming, PhD scientists or the man on the street? Who do you want to perform surgery on your kid, a trained and accredited surgeon or a randomly selected poll respondent? Then elitism has a role to play in our society. The government makes policies based on or impacting scientific, strategic, economic, and other matters where expertise is absolutely essential if you want good policies. Then elitism has a role to play in our government.

But obviously the possibility for reliance on elites to be abused is incredibly dangerous. There has to be a counterweight to elitism, and that counterweight is the consent of the governed. Our political system is designed to allow representatives (hopefully representing our elite in the best sense of the word) a wide range of latitude in governance, but to make them ultimately accountable to the people. It is neither populist nor elitist, but a fusion of the two.

So what happens when the balance between populism and elitism is disrupted? Well, take a look at the increasing partisanship and dysfunction in Washington D.C. since the rise of the Internet to get an example. Knowledge is power, and power can be abused. The Internet is, fundamentally, a communication technology that allows for the wide and targeted distribution of information. How much easier is it for activist groups (like the NRA) to micromanage elected representatives and then pass that information directly to their self-selecting constituents who have this information in the absence of any meaningful context. We complain that there’s so little real compromise in Washington, but who can compromise when there are hundreds of single-issue and ideological groups who are literally scoring our legislators on every vote they take?

Again: when I make an argument that says “less informed voters would be better” that ought to send up some red flags. But viewing it as less / more informed isn’t helpful. It’s not just about the amount of information that voters have, but also the kind of information that voters have. I would absolutely love to have voters who are more informed about the nature of our government, what the various branches are responsible for, and so on. I think that a kind of basic citizenship test before voting is a good idea (but not an unproblematic one). But when voters get myopic rankings on hot-button issues without any context: that’s more like noise than information. Voters don’t actually know what votes their representatives cast. They don’t even understand the arcane and complex procedures by which the House and Senate operate. They don’t know when a vote represents a pure capitulation, and when it represents a give-and-take. All they know is that on Position X Candidate Y has a D- from their favorite activist organization. So we’ve got a bunch of elected representatives who have to game the system with their votes in order to stay in office.

And that’s thanks to democracy.

What’s the solution? Well, there’s no silver bullet, but I do believe the first step is a recognition of what the American political system is for. And I don’t think that the American political system was designed or intended to get representatives to either guess what Americans would want if they were asked or merely act out their reactions to poll questions. I think the American political system harnesses the concept of consent of the governed to create accountability by creating healthy incentives. In short, representatives (in the past) have had more incentive to get good outcomes then to react to the preferred ideologies of their constituents. But, since we’ve lost an appreciation for that distinction, we risk reforms that will actually make the problem better rather than worse. Banning single-interest groups or clamping down on their free speech is not, in my mind, a viable solution. Reforming the way we create districts (to restrict gerrymandering), reforming the way we vote (to eliminate strategic voting), and reforming the schedule for primaries (to decrease entrenched special interests) all are.

In short: you have to know how the machine is supposed to work before you can understand how to repair or improve it.

This is particularly interesting in light of the “permission structures” speech that Obama gave. Graham and McCain have been, arguably, the lead spearchuckers on Benghazi in the Senate. Coincidentally, they’re also leading on the immigration bill.

I haven’t got into the weeds of the specific issues, but now having been self-aware for several election cycles and witnessing little change in the context of pompous, grand, ideological campaigns; and having observed our elected officials debate ad infinitum whether our government should be the size of a pea or a palace, I eventually came to the conclusion that any meaningful change will come from the bottom of a barrel which contains the most unsexy ideas imaginable. So when you say things like “gerrymandering” and “primary schedules”, I get really excited.

I like these ideas so much that I would love to see this become the raison d’etre of a viable third party, and I would happily jump ship to such party and let the R’s and D’s have their freudian size-of-government discussions in peace.

Do you have any thoughts on the role of term lengths and/or limits reforms to contribute to system reforms?

I’m not familiar with that speech, Galen. Fill me in?

I’m glad that you like the unsexy ideas, and I’d like to do something with them one day. I’m thinking about starting in Virginia (my home state) with state-wide reforms to the voting system, but I don’t even really know where to begin with that.

I don’t have any special expertise, but I’m generally skeptical that they would have a major impact. I also think there is the possibility of real costs when you have a ton of churn in government.

Overall, I think there’s a kind of super-naive idea of the citizen politician. The Founders may not have been professional politicians, but how much of this was because they were from a landed, genteel class that didn’t really need a profession? It’s not like we had a large number of middle-class politicians, did we? (Honestly: I’m not sure. That’s a real question.)

I’m OK with relative elites, or at least specialists, in office. I just want them more accountable and not subject to so many perverse incentives.

I like the idea of more specialist “elites” in office as a good balance to the elite career politician vs. the citizen politician. My husband will never run for office, but I would like to see more people like him in politics. He is a professional geologist who will graduate from law school next year. He has worked as a geologist for private business — oil companies, private environmental firms. He has worked extensively with the DEQ, EPA, various states, the public and private sector, and he has seen the messy legal, political, and scientific problems. He is often shocked by the low level of knowledge and experience displayed by fellow environmentalist law students and even some of his seasoned environmental law profs, who only experience the legal and academic side of things. He corrects them on basic areas of business, science, and regulatory realities, which they use to formulate their ideas and arguments. They read books that come from horrible sources, but those books champion a certain ideology. And the excited inexperienced student eats it up. Just an example: they seriously discussed the value of implementing China’s one-child policy in the U.S. as a way to control population and “save the environment” and completely dismissed the huge objections and realities of such a policy. This is a relatively conservative law school — Welcome to our future lawyers, judges, and lawmakers. Environmental politics in this country is truly maddening when you have some scientific knowledge and experience in the real world.

We definitely have elites in office already, LT, but they are the wrong kind of elites! Lawyers may be smart people, but in a sense they are largely folks who couldn’t hack it in a quantifiable discipline. And so, like you say, they really don’t know the first thing about science, business, or other realities.

As a general rule, I’m deeply distrustful of humanities and law because it seems to have become such an ideological monoculture in our society. I’m not sure why literature would necessarily have a political ideology, but there’s no denying that it does. Even the social sciences are deeply partisan.

Anyway, that’s all a bit of a tangent, but I definitely think that we will always have elites and they will–by definition–always have outsized power. Trying to make that reality go away ends up in denialism, and then we can’t compensate or mitigate the elitism. That’s the position we’re in today, when Sarah Palin was mocked for going to the kind of public universities that many Americans would be proud to attend while Democratic and Republican leaders all come from immaculate Ivy League backgrounds.

I’d rather have elites who are accountable and who are elite in ways that are actually beneficial. Such as more practical knowledge and experience (as you mentioned) and perhaps (dare I dream?) even in matters of personal character.

As written this applies to budget, but swap out references to a grand bargain with “immigration reform” and it’s the same idea:

http://tpmdc.talkingpointsmemo.com/2013/05/obamas-permission-structure-and-his-last-best-chance-for-a-budget-grand-bargain.php

As I see it, the third-party authentication at play here is an issues bankshot, where “who edited the talking points and when did they edit them?!” insulates McCain and Graham from the right in states where immigration reform is very problematic:

“Running in a conservative, Southern state that has proven friendly to insurgents in recent years, Graham has repeatedly poked his finger in the eye of the GOP base. He supported both of President Obama’s Supreme Court justices, muses about higher taxes to get a fiscal grand bargain and is among the leaders of the push to create a pathway to citizenship for illegal immigrants.

Graham’s fortunes could yet turn. Particularly if the immigration bill sparks a backlash, Graham could find himself in danger of suffering the same fate as other deal-making Republican senators who got outflanked on the right and lost primaries.

But for now, the South Carolinian appears to be a much safer bet for a third term than many would have predicted a few years ago when he backed Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan for the Supreme Court.

For the 57-year-old bachelor and Air Force reservist, politics and policy are his life’s passions and he’s determined to play a central role in the country’s big debates. This hunger for the limelight, and for addressing difficult issues, can lead him to trouble with his own party. Look no further than immigration. Representing a state with a minimal Hispanic population, there’s no political incentive for him to become so associated with such a contentious issue.

But his outspokenness and penchant to appear on center stage can also be an asset to Graham, as has been on vivid display since last September when he first seized on the killings of four Americans at the U.S. consulate in Libya.

“When people ask me, ‘Will you let [Benghazi] go?’ Hell no I’m not going to let this go!” he said to loud cheers at the state GOP convention here Saturday.

Issues like Benghazi, the handling of last month’s Boston Marathon bombing, the gun control debate – each of which saw Graham carve out a hard-line position — offer the Republican a chance to remind conservatives of the areas where they not only agree with him but where he’s a tenacious advocate for their cause.

And he does plenty of reminding. As is wellknown in even the outer fringes of the political universe, the wise-cracking and often off-message Graham is a ubiquitous presence on TV news programs. He’s on a Sunday show nearly every weekend, but, as important for his primary quandry, is also a fixture on Fox’s daytime programming. As South Carolina GOP chair Chad Connelly cracked at a Republican fundraiser here last weekend there are two things you can find at anytime, anywhere in the world: “Reruns of ‘Law and Order’ and Lindsey Graham being interviewed.”

If he’s not on the tube or in the Capitol, he’s invariably back home on the banquet circuit, making the case to Lions Clubs and Rotaries why immigration reform is essential while savaging President Obama on national security.

In Graham’s eyes, by loudly carrying the right-wing banner on some issues he buys himself some political capital to spend in other areas where he strays from the party line.

“Our country needs to fix problems and that’s who I am — I’m going to be a guy that will do the deal but I’m also going to be a guy that can throw the punch,” he said in an interview after his Saturday convention speech.

It’s the pugilistic side he’s been demonstrating of late that he believes has jogged memories of the more traditional conservative first elected to Congress in 1994 who came to fame as an impeachment manager on the House Judiciary Committee.

“What has helped me back home is that people remember the Lindsey from impeachment, they remember the guy who was leading the charge on conservative caucuses,” he said. “[Benghazi] and the second amendment stuff, that’s where I can throw a punch.”

Beyond his own considerable efforts making sure his conservative views get as much exposure as his practical side, Graham has been helped by circumstances.

Issues like Bengahzi and Boston that play to Graham’s strengths with the right have dominated the headlines while immigration reform, so far, lacks the punch it had when it was debated at the end of the Bush administration.”

http://dyn.politico.com/printstory.cfm?uuid=27D9C066-4CF4-4855-B00A-E0C51FB09411

I don’t think it’s a happy coincidence that McCain and Graham make the Sunday circuit weekend after weekend, lacing into Obama on Benghazi, and then come over for tea afterwards to talk immigration (which seems to be going swimmingly, at least in the Senate).

“Lawyers may be smart people, but in a sense they are largely folks who couldn’t hack it in a quantifiable discipline. And so, like you say, they really don’t know the first thing about science, business, or other realities.”

Neil Tyson Degrasse was on to something: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRemPvRxt9w

“A democracy, Mr. Cromwell, was a Greek drollery based on the foolish notion that there are extraordinary possibilities in very ordinary people.” The movie takes liberties with the history, of course, but it is a fascinating portrayal of the interplay between power, political necessity, and ideals. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dRFrXGkYjhM