You can find plenty of attacks on “traditional marriage” these days. These pieces generally take a historical approach, looking at how the institution of marriage has changed throughout history and how widely they differ from 1950s stereotypes. There is a legitimate point to this analysis, marriage has changed quite dramatically from time to time and from place to place, and there are certainly modern embellishments that are anachronistically applied to the tradition backwards throughout time.

Unfortunately, the political assumptions that frequently accompany such critiques distort the analysis. Closer inspection reveals that the same core aspects that defenders of traditional marriage emphasize are much, much older and more deeply embedded into the institution of marriage than critics and maybe even defenders of traditional marriage realize.

The proximate provocation for this post is a piece by Angela C. at By Common Consent: The Myth of Traditional Marriage.[ref]This piece is an extrapolation of the comment I left there.[/ref] The core assumption that leads Angela astray is that marriage is an invention. As she writes:

Depending on whom you ask, marriage was either invented by men to protect or to oppress women. And some men would argue that marriage was invented by women to domesticate men (a pouty version of the protection argument).

Of course, Angela is also employing the highly partisan assumption that the invention of marriage had to have been sexist: either the outright misogyny of exploitation or the insidious sexism of assuming women need protection. As objectionable as this assumption might be, it’s actually far less important than the subtle assumption that marriage is an invention.[ref]Astute readers might also point out that by dismissing any explanation in which women play a proactive role rather than exist as passive subjects she risks enacting a pernicious form of sexism herself.[/ref] Which is to say that it is a social construct.

The explanation of why this idea of social constructivism is associated with socially liberal politics is an interesting one, but it is mostly also outside the scope of this post. I will just point out that it is associated with socially liberal politics. The most obvious example, of course, is the argument that gender is a social construct distinct from biological sex.

Implicit in these theories is the peculiar notion that society is not biological. It is peculiar because it is most often embraced by those who either outright deny the role of a supernatural deity in creating humanity or at least downplay it in favor of scientific explanations. But it’s quite difficult to see how science can provide any metaphysical justification for treating humans and our society and its constructs as one class of beings and the natural world as another. It’s very much like the natural foods advocates who warn against eating anything “chemical” without realizing that everything is chemicals. Social constructivism—at least in its most extreme and naïve form—is a modern superstition.[ref]I anticipate getting some stern replies from those with expertise in this area. I welcome the contribution of experts, but the popular understanding of technical concepts is also a relevant target of analysis and critique.[/ref]

Implicit in these theories is the peculiar notion that society is not biological. It is peculiar because it is most often embraced by those who either outright deny the role of a supernatural deity in creating humanity or at least downplay it in favor of scientific explanations. But it’s quite difficult to see how science can provide any metaphysical justification for treating humans and our society and its constructs as one class of beings and the natural world as another. It’s very much like the natural foods advocates who warn against eating anything “chemical” without realizing that everything is chemicals. Social constructivism—at least in its most extreme and naïve form—is a modern superstition.[ref]I anticipate getting some stern replies from those with expertise in this area. I welcome the contribution of experts, but the popular understanding of technical concepts is also a relevant target of analysis and critique.[/ref]

So let us set aside the assumption that marriage is an invention, a deliberate construction willfully created by humans to accomplish a consciously desired end. I don’t mean to say let’s assume that marriage is not an invention. I’m merely saying: if we don’t make that assumption do we find any more likely candidate explanations? And, as it turns out, we do.

To understand the origins of marriage we first have to understand a little bit about the differences between human beings and other animals. The answer is that humans have evolved to make a very high-risk, high-reward tradeoff. The risk is that our offspring are basically helpless for an exceptionally prolonged period of time. This requires enormous resources to feed them and keep them safe. The reward is that, in exchange for that helplessness, our offspring are incredible learners (and then, later in life, incredible teachers). Learning and teaching are what humans do better than any other species. Human babies are useless at running or fighting or hiding, but they are tremendous geniuses at things like language acquisition. We have highly plastic brains that take a long time to learn anything, but that can eventually learn just about anything. That single difference pretty much explains the difference between chimps using sticks to forage for ants and humans launching the Space Shuttle.

The reason why this change has such huge dividends is that it separated human knowledge from human genetics. Other animals are capable of some pretty amazing behaviors (like migration), but these are often instinctual. That means the information is genetic. Advantage: no one has to teach it. Disadvantage: the animals can only learn and change as the speed of genetic evolution, which takes place across hundreds or thousands of generations. If the migration pattern needs to change in an abrupt way, monarch butterflies can’t just tell the next generation to take a different route next time.

Humans, on the other hand, initially used society as a repository for knowledge. Each generation could teach the skills (from language to tool use) to the next generation. This meant that exchange of knowledge (for example when a new tool was discovered) could be exceptionally rapid both across generations and across tribes. That was the basis for creating (eventually) written language, which only further increased the pace since now our knowledge can be transmitted and reproduced even more rapidly and cheaply and widely. In short: other animals learn at the speed of genetics. Humans learn at the speed of memetics which, in the Internet Age, is the speed of light.

This is pretty cutting-edge science because it relies on concepts like group selection that—although initially proposed by Darwin—have been considered more or less impossible until recently. No one could figure out how to make it work: why would one individual sacrifice altruistically in order to benefit his tribe? In short: how do you get trust? Advances in game theory and complexity science have for the first time made it possible to illustrate how these obstacles can be overcome, and therefore how it is possible for groups to compete against each other (and therefore to have group evolution) rather than just individual organisms.

So now we’ve learned two key things. The first is that the chief difference between humans and other organisms is that we have really, really expensive but also really, really high-performing offspring. The second is that this idea carries with it the notion that groups compete and evolve, which is to say that societies can compete and evolve. Most notably, these are intrinsic to what it means to be a human being. They predate any history and go back to the origins of our species.

Which means that marriage predates our history and goes back to the origin of our species, provided we define marriage as (1) monogamous sexual pairing of males and females who (2) cooperate to feed, protect, and teach their offspring. This behavior must be as old as humanity because humanity is impossible without it. Without cooperation, human children cannot be raised by subsistence cultures. They are too expensive. But without sexual monogamy, males and females are not equally vested in the offspring. These behaviors therefore co-evolved with humanity itself.

So we’ve just bypassed all the historical, cross-cultural analysis of formal marriage institutions by a couple hundred thousand years, at least. So much for an “invention.” What does the story look like from there?

Well, all of the individual cultural variations around the kernel of marriage (monogamy and cooperative child-rearing) end up only being possible because of the integral role that the kernel of marriage played in our society. The logic can’t work any other way. Why would someone use marriage as the basis for political alliance, for example, if monogamous, child-rearing relationships weren’t already fundamental to human society? No one would think to invent marriage from scratch for the purposes of political alliance and, if someone did think of it, it would never work because there would be no foundation to build upon.

So it is absolutely true that marriage comes in a wide variety of cultural and legal and historical instantiations, but it is only the variety that is in any sense invented or constructed or arbitrary. They inventions only exist because there was a stable foundation upon which to build them.

Oral language was not invented. It evolved. Written language was not invented. It evolved. Nation-states were not invented. They evolved. Markets were not invented. They evolved. And, like these other bedrock institutions, marriage was not invented. It evolved. Just as oral and written languages vary widely, just as forms of government run the gamut from tribal chiefs to Prime Ministers, and just as the laws for doing business vary from place to place: so do does the institution of marriage alter and change from time to time and from place to place.

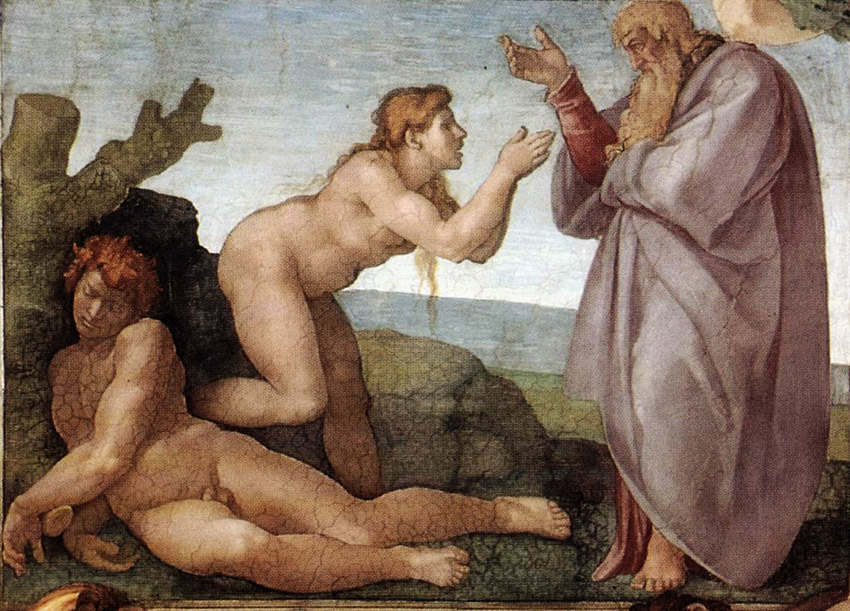

But there are individual characteristics that languages, governments, and markets must have in order to exist at all, and similarly there are traits that marriage—despite its many variations—must exhibit in order to exist. Those are sexual monogamy between men and women raising their biological children. Which, not at all coincidentally, are the characteristics that are of utmost importance in the minds of social conservatives defending “traditional marriage.” Whether you believe that marriage was ordained of God by divine fiat in a literal Garden of Eden, was orchestrated by God through the process of natural selection and evolution, or simply evolved spontaneously without any help from a Creator of any kind: marriage remains the fundamental institution that made the human species possible.

The key lesson to learn here is not necessarily that marriage should never change. Marriage—the entire package including the biological kernel and the social embellishments on top of it—changes all the time. Some of those innovations are bad. When society codifies marriage in a way that treats women as property to be bought or sold or gives men a legal right to rape their wives, then society is leveraging the power of the biological kernel of marriage to do great evil. But when marriage is used as a model to care for those in need—like with fostering or with adopting children—then in that case we’re building something beautiful and worthy on top of the foundation that we’ve inherited to work with.

Because this isn’t an argument that marriage should never change, this post cannot function as a direct argument against same-sex marriage, open marriages, or other currently controversial topics. It is possible to believe that the kernel of marriage has filled its evolutionary purpose. Now that we have enormously greater economic prosperity, perhaps the old rationales no longer apply.

This may be so, but at least those who advocate changes to marriage at a fundamental level ought to admit that they are tinkering with the evolutionary foundations of human society. To use a computer analogy: debates about marriage that get to its essential characteristics are not like swapping out one app for another. They are about making changes to the kernel of the operating system. It would be best to know what one is doing before one undertakes such an endeavor. Those propounding the “myth of traditional marriage” manifestly fail to apprehend its true nature and significance. Therefore, they are the last folks I want involved in the process.

Virtually nothing in this crucial paragraph is true:

Whether raising human children is too expensive for a subsistence culture without cooperation ([B]) depends on the harshness of the environment. In an environment of relative plenty, in which one is competing primarily against other humans, raising children is neither too expensive in absolute terms, nor does it put one at a competitive disadvantage. Even if it were true that cooperation was necessary in the context of our evolution (which is quite plausible, even if not certain), it would not follow that the cooperation need occur at the level of couples, contra [A]. It’s consistent with the need for cooperation that they be raised collectively by a tribe, for example.

Similarly, males and females need not be equally vested in the offspring, contra [C]. Indeed, I have rarely heard of a culture in which they were. Even when monogamy is a standard, it cannot be the sort of guarantee of paternity that biology affords a woman, which is often offered as a partial reason that men are generally less directly attached to their children than women.

I suspect your conclusion is correct–the institution of marriage gradually evolved in response to many pressures rather than being abruptly invented to accomplish a single goal. So the overarching point seems pretty sensible (though I’d like to save a little room for the possibility that there’s some amount of speaking with the vulgar going on). But if inadequate clarity on the rise of marriage makes one ill-suited to decide what it ought to be like in the future, it seems to me that we’re all in the dark.

Kelsey-

So there are three propositions in contention:

1. Some kind of cooperative bonding was necessary because human children are so expensive that they require cooperation to raise.

2. Monogamy was the dominant form of bonding because it ensured that the two most closely biologically related adults to the child (mother and father) were equally certain of their genetic investment.

3. As a consequence of (1) and (2), marriage (defined as monogamous coupling for the purpose of raising children) co-evolved with humanity.

I think you can argue that I may have over-stated (1) in my original post. But I think you’ve gone even farther in the opposite direction when you write that:

I think it’s wrong to say that a woman alone can adequately care for her child in a subsistence environment. Part of this is because there’s a lot more than food and shelter at stake. Human children require constant interaction in order to develop neurologically, and that’s exhausting. Any mom can tell you that, and that’s in modern society with a husband.

But even if, for the sake of argument, we say that a woman alone can provide for her child in a subsistence environment, there’s no way to say that she isn’t at a competitive disadvantage vs. a man and a woman who cooperate to provide for their child. A child with two parents is going to have roughly double the resources to benefit from vs. a child with one parent, and this is true no matter how the two parents divide up the labor.

However, I’ll also quote from one of the books that’s been most influential on my thinking here to provide some additional support for my allegations: The Righteous Mind, by Jonathan Haidt. In the chapter on the co-evolution of human biology with human culture called “Why Are We So Groupish,” he writes:

So I think Haidt strongly supports my argument that two-parents over one-parent has a strong competitive advantage, even if you’re not willing to go as far as saying that they are necessary.

Which brings us to the second point: buy why pair bonding? Why not just a group of adults who all cooperate together to take care of children, like a group of chimpanzees?

The important thing here is to note that group selection doesn’t rule-out individual selection. We are, as Haidt says, 90% chimp and 10% bee. The 90% chimp says that no human being wants to expend huge resources guaranteeing that someone else’s genes get to survive. We want our own genes to survive. Keep in mind, that I’m not talking about motivations that consciously drive a modern human being. I’m talking about evolutionary forces at work a quarter of a million years ago (or more) when humans were just diverging from other primates. At that time, monogamy would absolutely have worked to create more incentive for the father and the mother to have been equally invested in their offspring.

This is why monogamy, while certainly not universal, is also not uncommon in animal species. Crows, for example, are also highly intelligent and highly cooperative. They are one of the only animals other than humans to be capable of displacement communication. And they tend to mate for life. Monogamy is not the only way to integrate individual incentives with group incentives (I think in chimpanzee groups all males mate with all females so that it’s impossible to know for sure which male sired which baby chimp, which keeps the males from killing the baby chimps), but it is an adaptation and certainly seems to be the one that humans evolved to use.

And, if I’m right about the first two propositions, than the third (that this is an ancient adaptation) follows quite nicely.

Now, my argument isn’t the same as Haidt’s. He is arguing, based on multi-level evolution, for the origins of ultrasociality and, furthermore, for viewing human society and culture as evolved. I’m using that foundation and going just slightly farther to argue that one of the things that human society and culture evolved is marriage, in the form of pair-bonding to raise offspring.

What Kelsey Rinella says. In addition (or perhaps just piling on) an argument for cooperation does little to address monogamy, man-woman (only) pairing, and the expectation of permanence, that are all part of what I believe people mean when they advocate for “traditional marriage”.

Nor does it speak to the language, the word “marriage” itself. That there is some kind of cooperative activity involved in rearing children does not say that behavior is called “marriage”. A plausible (at least) argument can be made that the word developed or came into use to define property rights, including legitimacy and inheritance. In the realm of law rather than sociology.

No question that the negative cast about traditional marriage might be based on unpleasant personal experiences. For whatever reason, there are bad marriages and people who just make bad marriage partners. To assume that your personal or anecdotal good or bad experience characterizes marriage practices in collective consideration is nothing short of bigotry.

I agree, we must assume rationally, just by fact of the more generalized successful historic results of marriage tradition, that it IS a long-standing historic practice and has generally served well. The idea that these traditions must now be opposed or superceded by those who favor women’s rights or equality or some other trendy progressive buzzword is unsupported by the longer historic legacy.

Chris-

I do recognize that the cooperation argument and the monogamy argument are separate issues, and I’ve addressed that in my reply to Kelsey.

You raise a very good point, however, which is the permanence issue.

For starters, my attempt is not to simply reverse-engineer an evolutionary just-so story to vindicate traditional (i.e. Western, mid-20th century) conceptions of marriage. I’m outlining a core of the practice, and must necessarily exclude some things that I find favorable from the analysis. I’m a fan of romantic love, but it’s not necessarily essential to the definition. I’m also a big fan of equality and respect: they aren’t in there either. It’s a stripped-down, functionalist definition of marriage. To use another analogy, I’m talking about the chasis of marriage. A society still has to add its own engine, wheels, etc. to make the institution viable.

So is permanence a part of the core, or an add-on? First glance response is that it’s probably not. The pair-bond would need to last until the offspring were mature and/or until the couple were no longer fertile (which ever comes last), but how long did ancient human beings live after menopause? What’s the relationship between the relatively long period of time women live after fertility and other evolutionary pressures? I’ll need to think about that some more.

“Which means that marriage predates our history and goes back to the origin of our species, provided we define marriage as (1) monogamous sexual pairing of males and females who (2) cooperate to feed, protect, and teach their offspring. This behavior must be as old as humanity because humanity is impossible without it. Without cooperation, human children cannot be raised by subsistence cultures. They are too expensive. But without sexual monogamy, males and females are not equally vested in the offspring. These behaviors therefore co-evolved with humanity itself.”

I’m no expert, but the reading that I’ve done on the topic suggests that your summary and conclusions are almost certainly not correct.

In particular, anthropologists and scholars who study the evolution of human society tend to believe that humans are a species which employs a “mixed reproductive strategy” consisting of some sexual pair bonds as well as other sexual interactions. You see this discussed in Jared Diamond’s good summary about the evolution of human sexuality, _Why is Sex Fun?_ You also see it in writings from scholars like Sarah Hrdy.

If humans were a permanent monogamous pair-bonding species — and there are such species in the animal kingdom — then we’re designed all wrong. Human men produce way too much sperm for that social structure. Human women’s concealed ovulation means that humans end up with lots of non-procreative sex. Both of these are significant energy expenditures which don’t make evolutionary sense if humans were designed for permanent monogamous pair-bonding.

On the flip side, humans don’t produce _enough_ sperm or have _enough_ sex to function as a purely promiscuous species like bonobos, who don’t have pair bonds at all.

Human evolution indicates a mixed reproductive strategy, where pair-bond sex plays an important role but is not the only reproductive avenue.

Of course, just because something is evolutionary doesn’t mean we have to follow it. Infanticide of competing infants can be a useful evolutionary strategy but we should not do it.

But I’m reasonably sure that the existing anthropological evidence does not support a descriptive claim that humans are designed for permanent monogamous pair bonds.

“Which means that marriage predates our history and goes back to the origin of our species, provided we define marriage as (1) monogamous sexual pairing of males and females who (2) cooperate to feed, protect, and teach their offspring. This behavior must be as old as humanity because humanity is impossible without it. Without cooperation, human children cannot be raised by subsistence cultures. They are too expensive. But without sexual monogamy, males and females are not equally vested in the offspring. These behaviors therefore co-evolved with humanity itself.”

This logic does not follow.

Even if we accept your arbitrary definition of marriage by superimposing the political term, the concept doesn’t hold up. Monogamy is not the norm. Pair bonding is usually temporary and erratic. And even when monogamy can be observed in mammals, it tends to be serial monogamy by the female only (who will exchange her mate for a superior one should he come along). Mammalian males, with no biological investment required, tend to roam to the beat of a testosterone driven drum.

As you mentioned, our closest relatives the chimpanzee, in no way model this enlightened albeit arbitrary definition of marriage. And neither do humans until relatively recent in history.

The most you could argue is that humans are gradually developing a selective benefit in favor of faithful monogamous pair bonding (hypothetical ) and “traditional marriage” is a recent social evolutionary invention (very reasonable).

Kaimi-

Just a note: I’m having a very good (though long) discussion about this with Chelsea Shields Strayer on my Facebook wall (it’s public, so you should be able to see it). Some of the specific objections you raise are being discussed there. The short version is that I’m questioning the reliance on physiology as a proxy for behavior not in a general sense (although that’s a well-known consideration) but explicitly in the case of human evolution because that evolution is meta-biological. This means that when humans became the ultrasocial we stopped passing on information from generation to generation only through our genes and started passing it on through our society as well. This is the defining characteristic of human physiology, in fact: we’re evolved to be highly social so that we no longer are constrained by genetic evolution. There’s no reason to believe evolution requires information to be expressed through genes (rather than computer code or social memes), so the same evolution that shaped our bodies could very well continue to shape our minds once this jump has been made. However, evolution would now (1) be somewhat unconnected from physiology and (2) would proceed at a much more rapid pace.

Therefore, the objections based on the size of our testes, for example, simply might not work for humans the way that they do for chimpanzees.

The second objection–about permanence of the monogamous bonds–is one that I think is much more serious and I need to think about some more. (You’re not the first to raise it in this thread!)

Corey P-

I’m not really defining marriage. I’m defining what I see as an evolutionary core of marriage, about which different societies have constructed their own variations for both good and ill.

The definition I proposed for that core is not arbitrary. It is an attempt to work out a probable core given (1) a specific theory of evolution I’m working with, (2) the world as it exists today, and (3) the unique elements of human beings.

Given point #3 above, reference to chimps or other mammals isn’t very illuminating. One of the great puzzles that we have to address in human evolution is the fact that, physiologically, we’re so similar to our primate cousins and yet the results are so starkly different. What explains this gap? I argue–and this is not my own invention–that it is our ultrasocial nature. I think explain that this ultrasociality entails that for human beings, evolution proceeds not only at the genetic level, but also at the social level. This further underscores the dangers of assuming too much based on human physiology, let alone chimpanzee physiology.

This is a very confused critique, since “evolutionary invention” is a contradiction in terms. An invention is something people create for a given end. Evolution is a mindless algorithm. It also suffers from the assumption that evolution on a genetic level is somehow a different kind of process as evolution on a social level, but that might not be the case.

This seems to cut both ways, though. If we are connected to our offspring primarily memetically, why is there such emphasis on raising only your genetic children? That seems to be a crucial element of the explanation for male-female pair bonding, but you seem to have just conceded that it’s a uniquely weak explanatory factor in humans.

With respect to my earlier comment, you’re right that a single mother is at a competitive disadvantage to pair-bonded parents. However, that merely explains how, if minimal marriage had already evolved, it might crowd out single parenthood. It does nothing to establish your point that marriage had to evolve or we’d all have died; the point I’m trying to make is that we don’t know enough about the environment in which we evolved to make that claim. If pair bonding had never come along, we might have come through just fine. That means we can’t assume from this evidence that we must have evolved pair-bonding. Moreover, while you’re clearly right that passing on the massive amounts of culture we have takes a tremendous amount of effort, most of that culture didn’t exist during our evolution. Hundreds of person-hours go into teaching modern children to read and write, for example; extrapolating the educational needs of proto-humans from our experiences is highly unreliable.

Two points: (1) I’m not sure that an evolutionary theory of marriage disconnected from physiology and instead rooted in rapid social transmission is particularly conservative (either methodologically or in terms of outcomes) and (2) I’m with you that we should be reluctant to tinker with institutions that have stood the test of time. On the other hand, there is something that has always struck me as odd about the argument that the institution of marriage is, on the one hand, so powerful that it can do all of these amazing things (i.e., tame human passions and channel them into productive relationships, foster fidelity and cohesiveness, etc.) but on the other hand, the institution is apparently so brittle that if we extend it to homosexuals, the whole thing will fall apart. In other words, there’s tinkering and then there’s tinkering. If we were trying to redefine marriage so as to eliminate the whole monogamy aspect of it, then you could count me as very worried. But keeping the institution intact and just extending it to people who want to form a monogamous relationship? I guess I’m not particularly worried about the social implications of gay marriage in this country because of my faith in traditional marriage, not in spite of it.