I’ll just start with my thesis: the only rational and consistent outlook of materialist atheism (hereafter referred to simply as atheism for brevity) is that life is pointless. Believing otherwise inevitably involves some degree of delusion or distraction.

I suppose them fightin’ words need support. First, I would point out the following. I will die. You will die. Everyone we know, helped, or hurt will die. Everything we ever accomplished will disappear. The earth will cease to support life. The sun will go supernova. And eventually the ultimate heat death of the universe will occur, beyond which nothing will ever occur again (at least in this universe, but let’s leave out multiverse theory). In that context, how can anything matter?

The most common response I hear is that you create your own purpose, sometimes followed by quotes from existentialist philosophers. Within an atheistic point of view, that sounds like the equivalent of saying ‘I will believe in stories that give my life purpose or distract me from my inevitable and permanent non-existence,’ which should appear disturbingly similar to the purpose of religion as understood by many atheists.

Furthermore, saying you create your own purpose seems like saying that Sisyphus would’ve had a purpose if the gods had attached a rolling-counter to his boulder to keep him occupied. SMBC wrote a comic to that effect.

Sisyphus could have attached any personal purpose imaginable to his existence, and we would still say his existence is pointless because it has no final point or purpose. The boulder goes up the hill, and then it goes down, leaving Sisyphus with a net nothing. We expect to meet the same fate under an atheistic point of view. We spend our existence pushing our boulder of accomplishments up the hill of life, and whether in a few decades, a century, or a millennium, that boulder will come right back to where it started. We will be forgotten, and everything and everyone we influenced will cease to exist. We ultimately did it all for no objective purpose.

The next response is usually that my opinion doesn’t really count since I’m not an atheist. I would bring up that I was an atheist, and this question mattered to me, but I think it’s more effective to point that this isn’t my opinion originally. It’s the opinion of many atheist and agnostic thinkers throughout history. For example, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes about Albert Camus that:

Camus sees this question of suicide as a natural response to an underlying premise, namely that life is absurd in a variety of ways. As we have seen, both the presence and absence of life (i.e., death) give rise to the condition: it is absurd to continually seek meaning in life when there is none, and it is absurd to hope for some form of continued existence after death given that the latter results in our extinction.

Leo Tolstoy searched for meaning in life and ultimately found none within a material framework, bringing him to the edge of suicide before his conversion to Christianity. He wrote in his book Confessions:

I sought in all the sciences, but far from finding what I wanted, became convinced that all who like myself had sought in knowledge for the meaning of life had found nothing. And not only had they found nothing, but they had plainly acknowledged that the very thing which made me despair–namely the senselessness of life–is the one indubitable thing man can know.

…

My question–that which at the age of fifty brought me to the verge of suicide–was the simplest of questions, lying in the soul of every man from the foolish child to the wisest elder: it was a question without an answer to which one cannot live, as I had found by experience. It was: “What will come of what I am doing today or shall do tomorrow? What will come of my whole life?”

Differently expressed, the question is: “Why should I live, why wish for anything, or do anything?” It can also be expressed thus: “Is there any meaning in my life that the inevitable death awaiting me does not destroy?”

Somerset Maugham, a famous 20th century writer and agnostic, stated:

If one puts aside the existence of God and the survival after life as too doubtful . . . one has to make up one’s mind as to the use of life. If death ends it all, if I have neither to hope for good nor to fear evil, I must ask myself what I am here for, and how in these circumstances I must conduct myself. Now the answer is plain, but so unpalatable that most will not face it. There is no meaning for life, and life has no meaning.

Personally, my favorite answer comes from Hume. In the face of life’s inevitable end, Hume recommended the very modern solution of distraction:

Where am I, or what? From what causes do I derive my existence, and to what condition shall I return? … I am confounded with all these questions, and begin to fancy myself in the most deplorable condition imaginable, environed with the deepest darkness, and utterly deprived of the use of every member and faculty.

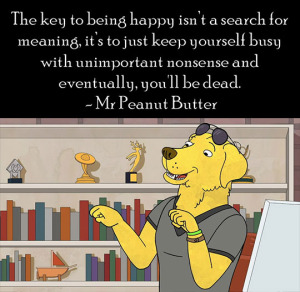

Most fortunately it happens, that since Reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, Nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures me of this philosophical melancholy and delirium, either by relaxing this bent of mind, or by some avocation, and lively impression of my senses, which obliterate all these chimeras. I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends. And when, after three or four hours’ amusement, I would return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strained, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.

Which I would wager is the most common answer today. I suppose every person feels like they live in an age of unparalleled distraction, but I truly believe that the amount of distraction available to human beings today is greater than almost any period of history. In that context, nobody really needs to bother with whether life has meaning or not.

A brave new world indeed.

Mostly, I write this post as a call for consistency and rationality. I came of age in an atheism that espoused facing the truth, no matter how bleak. Here is the truth. Under an atheistic point of view, life has no objective meaning, so the the options are making up your own (unprovable) story, finding sufficient distraction until you die, or nihilism. Or as my friend Reece succinctly put it:

In my mind, there are really only two kinds of atheists. There is make-believe pretend atheism, and then there is nihilism.

Ultimately, we won’t know until we’re dead who is right. However, we can know in this life who lives consistently with what they believe.

Bryan, just for clarification, what do you think would specifically constitute worldview-consistent behavior for someone who thinks that their existence has no ultimate meaning or purpose?

I am an atheist, and believe life has no objective meaning. Were I to view life as a trial to be endured, I might wonder why I bothered. As it happens, though, life is pretty great. So it seems I read the Hume quote differently–it’s not merely that pleasurable experiences distract us from the question of whether life has meaning, they demonstrate that it doesn’t matter whether life has meaning or not, and so make the question uninteresting.

As a matter of psychology, I still find some work inherently satisfying. Not laundry, I confess, but teaching, and developing useful exercises for others to use in their teaching, for example. I think this is the sort of thing that’s supposed to not happen if life has no objective meaning, and I confess I have wondered whether I am merely avoiding the question. But it certainly seems to me that I can entertain the meaninglessness of life while deriving satisfaction from the sort of contribution to the welfare of others which would be a prime candidate for disqualification. It even seems to me faintly immoral to derive such satisfaction only if helping others contributes to the meaning of one’s own life.

Then again, it also seems faintly immoral to do it for the satisfaction of it, which is my motivation. I seem to have internalized a touch of Kant, despite my best efforts.

Nihilism is a drag, which is a good enough reason to stay out of that camp. A more compelling reason is knowing I might be wrong. The “dunno, hope not” option sits between Reece’s two kinds of make-believe and nihilist atheism.

“Bryan, just for clarification, what do you think would specifically constitute worldview-consistent behavior for someone who thinks that their existence has no ultimate meaning or purpose?”

I’d say (admittedly vaguely) that we would need to give up any sense that there is anything worth doing or anything that needs to be done with our lives. What that looks like in practice, I can’t say for sure, since fully embracing nihilism is naturally very difficult (if not impossible) for human beings. My practice would probably be the Tolstoy route: Might as well kill myself and get this farce over with. Camus argues that suicide is not a valid choice because it negates the question of life, but why should I care about answering the question in the first place? And if I can’t find the courage to overcome my instinctual aversion to suicide, I’d go next for a life of hedonism straight from the school of Epicurus. In a life devoid of purpose, maximizing my pleasure and minimizing my pain seems the most logical to me.

“Nihilism is a drag, which is a good enough reason to stay out of that camp. A more compelling reason is knowing I might be wrong.”

These are compelling reasons, but also irrational. The fact that nihilism is unappealing has no bearing on its truth. Knowing you might be wrong in this case seems like a restatement of the first reason in the guise of metaphysical humility: This outcome is excessively unappealing and essentially impossible to live, so I’m going to hedge my bets on the outcome. It’d also be a bit schizophrenic to base our beliefs on materialist atheism, except when the question becomes if life has purpose or not, and then shift to an agnostic position because nihilism is unpleasant.

“Materialist atheism” without a commitment to nihilism makes as much sense as keeping your cards until you see the river. That is to say: it costs you little to stay in the game, and you definitely lose if you fold early. Outside of the metaphor: folding early, you never know if you had the cards to win all along. As with any hand, you’ll probably lose, but that’s no reason not to see it through.

“‘Materialist atheism’ without a commitment to nihilism makes as much sense as keeping your cards until you see the river. That is to say: it costs you little to stay in the game, and you definitely lose if you fold early. Outside of the metaphor: folding early, you never know if you had the cards to win all along. As with any hand, you’ll probably lose, but that’s no reason not to see it through.”

You make a good point, but I thought atheists despised anything resembling Pascal’s Wager :P. And if you’re willing to stay in the game on those grounds, why stick with atheism? Why not place a wager on the faith that seems most reasonable since you’re hoping one of them is true? At very least deism seems like a reasonable bet if you can’t get behind special revelation.

“… the only rational and consistent outlook of materialist atheism (hereafter referred to simply as atheism for brevity) is that life is pointless.”

I actually see a different thesis in your writing. Or, rather, I see some premises that are up for much more debate than your conclusion towards material atheism; I see you basing your arguments on the ideas that:

a) life must have an ultimate, objective purpose,

b) everything that doesn’t stand to serve a purpose/this purpose is bad

and, perhaps

c) spirituality is the only way to live this purpose.

This may seem like a bizarre point, especially given how so deeply rooted it seems to be in everything we do, but truly — if we’re going to be thorough, why would we assume that this exists when we don’t no real basis for assuming it does? Why does it all need to be eternal and purposeful? How do you even define something having a “purpose” or a “point”? Does a “purpose” have to be an end objective that is somehow tangible or spiritual? These seem like much larger points that must be addressed and not just taken for granted.

What if someone could not come to any metaphysical conclusions about the world but lived an ultimately positive and helpful life? Would they be pointless and bad? If a person, who couldn’t seem to find a connection with a God or religion – or was simply atheist – spent their life just trying to be a good person and ended up succeeding and brought happiness and a higher quality of life to everyone; if they themselves were content but felt that it never had a single, lasting point, would their existence in the world really be so unsatisfactory?

Or, let’s look at Sysiphus. Why is this story so abhorrent? You say the following:

“Sisyphus could have attached any personal purpose imaginable to his existence, and we would still say his existence is pointless because it has no final point or purpose. The boulder goes up the hill, and then it goes down, leaving Sisyphus with a net nothing. We expect to meet the same fate under an atheistic point of view. We spend our existence pushing our boulder of accomplishments up the hill of life, and whether in a few decades, a century, or a millennium, that boulder will come right back to where it started. We will be forgotten, and everything and everyone we influenced will cease to exist. We ultimately did it all for no objective purpose.”

Why is the boulder metaphor so ugly to you, especially when you even go on to give it a slightly happier extension – the idea that someone actually got to *accomplish* things in their boulder-for-existence life? As in my previous example, can you really say that something was bad if they did great and selfless things?

What about the smaller things in life? Do they have to contribute to this purpose or have their own little purpose? If this were the case, why would you ever eat hamburgers or highly sugary foods? The only good they bring is a quick, temporary satisfaction to your life and then, for the most part, leave a negative impact on your body, particularly when eaten in excess. This has never stopped you from eating burgers, but if you were truly “living consistently with what you believe”, would you not stop eating these today for both this and many other ethical reasons?

I also wanted to address this point on the end of your essay:

“Ultimately, we won’t know until we’re dead who is right.”

Why is it about who is right? Better question: why is there even a “right”? How do we even know there is a “right” to any of this?

I’m also going to be a little critical of Reece’s message:

“In my mind, there are really only two kinds of atheists. There is make-believe pretend atheism, and then there is nihilism.”

Honestly, this seems rather dogmatic and not very thoughtful. Why is a higher power so absolutely necessary to this entire basis of metaphysics? There are an uncountable number of ways within the realm of metaphysics as to the understand of the fiber of our world and many of which hold greatly complex ideas that exist without a necessary being (aka a God.)

Not directly correlating to your atheist position here, you quote Camus and try to point towards his philosophy of the absurd to attribute to this idea that material atheism has to equate to nihilism (which you seem to hold as rather repulsive.) I would argue that you’re incorrect in your interpretation of Camus, especially in how he relates to atheism/agnosticism. Perhaps the most important thing Camus brought to philosophy is the question of whether we should all just kill ourselves or not. Scholars of Camus’ agree with virtually no controversy that Camus’ main conclusion is that even though life has no inherent or objectiveprinciple, it is still worth living. Take this important quote also from SEP (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy):

“Accepting absurdity as the mood of the times, he asks above all whether and how to live in the face of it. “Does the absurd dictate death” (MS, 9)? But he does not argue this question either, and rather chooses to demonstrate the attitude towards life that would deter suicide. In other words, the main concern of the book is to sketch ways of living our lives so as to make them worth living despite their being meaningless.”

__________

I am going to stop here. I find your faith and your writing highly commendable, but I think the arguments you are making are against points and people which are hardly even sophomoric in nature. I have taken such an interest in religion since we first talked about it over a year ago that I have taken it upon myself to take classes and study it at an academic level, and from this I can now honestly tell you that even after rigorous study I know almost nothing. The debates regarding God amongst the field of philosophy, metaphysics, and religion are so unbelievably dense that a short blog article and even my corresponding reply do it no justice.

I also want to let you know that, within academia, both atheists and deists of all sorts tend to be highly respectful of each others positions; atheists commend good arguments for deism and deists give respect to atheists. I say this because it seems the debates on the metaphysics of God amongst laymen – let alone even fairly well educated people – tend to dwindle into fiery attacks fueled by emotion, and I can’t help but feel that your writing and views have been affected and hurt by this, too. I encourage you to not be affected by these typical arguments and to seek more scholarly debate if you wish to enhance your own writing and your understanding on the topic.

Bryan: “why stick with atheism? Why not place a wager on the faith that seems most reasonable since you’re hoping one of them is true?”

Atheism seems most reasonable. The point of the poker metaphor was to illustrate the disadvantage of wagering before you’re required to. The reverse of Pascal’s wager.