UPDATE: Although this post was published on August 24, 2017, it was written weeks ago. Notably, before Charlottesville. I’ll be writing a followup in light of recent events for the near future.

Despite the fact that overt, explicit racism is widely rejected and condemned within the United States, racially disparate outcomes remain endemic. One particular blatant example of this is the racially unequal justice system we have in this country. In super-short terms, blacks and whites use illegal drugs at about the same rates, but black people are more likely to be arrested, charged with more serious crimes, and serve longer sentences than whites.[ref]For the longer version, you can read my entire review of The New Jim Crow.[/ref]

Contemporary definitions of racism–of which there are basically two–attempt to explain why America continues to be a place with racially unfair outcomes even though overt racism has long since been marginalized. The first contemporary definition of racism is about systematic racism. According to this definition, prejudice is a feeling of animus against a person/people based on their race, discrimination is unequal treatment stemming from prejudice, and racism is an attribute of social systems and institutions where prejudice and discrimination have become ingrained. Accordingly, America can be a white supremacy without any white supremacists, because the overt prejudices of the past have been absorbed into our institutions (like the criminal justice system) and have taken on a life of their own. If the system is racially biased, then even racially unbiased people are not enough to get racial justice. It would be like playing a game with loaded dice. Even if the other players are 100% honest, their dice are still loaded, and so the outcome is still not fair. If you accuse them of cheating, they will be defensive because–in a sense–they are playing the game honestly. But as long as their dice are loaded (and yours are not), the game is still rigged.

Second, we have the idea of implicit racism. This is the idea that even people who really and sincerely believe that they are not racist may harbor unconscious racial prejudice. This is based on implicit-association tests and the theory that tribalism is basically hard-coded in human beings. These two findings–the empirical results of implicit-association tests and theories about the innateness of human tribalism–are not necessarily connected, but they come together in a phrase you’ve almost certainly heard by now: “everyone is racist.”

Thus, racial injustice can remain without overt racism because (in the case of systemic racism) racism is now located inside of institutions instead of inside of people and/or because (in the case of implicit racism) racism is now located inside people’s unconscious minds instead of their conscious minds.

So far, so good. Both of the new definitions (which are not mutually exclusive) provide promising avenues to understand ongoing racial disparity in the United States and seek to redress it. But this is where we run into a serious problem. As promising as these avenues might be, they certainly take us onto more ambiguous and complex territory than civil rights struggles of the past. The more overt racial injustice is, the simpler it is. Slavery and Jim Crow are not nuanced issues. But now we’re talking about how to fight racism in a world where nobody is racist anymore (at least not consciously). And just when things start to get tricky, the problem of perverse incentives rears its ugly head.

Perverse incentives are “incentives that [have] an unintended and undesirable result which is contrary to the interests of the incentive makers.”[ref]Wikipedia[/ref] In the fight against racial injustice there are basically two kinds of perverse incentive: institution and personal.

Institutional perverse incentives arise whenever you have an institution with a mission statement to eliminate something. The problem is that if the institution ever truly succeeds then it is essentially committing suicide and everyone who works for that institution has to go find not only a new job, but a new calling and sense of identity.

If conspiracy theories are your thing, then it’s not hard to spin lots of them based on this insight. Instead of fighting poverty, maybe government agencies perpetuate poverty in order to enlarge their budgets, expand their workforces, and enhance their prestige. But you don’t have to go that far. In practice, it’s far more likely that an institution dedicated to ending something will have two simple characteristics. First, it will exaggerate the threat. Second, it will be studiously uninterested in finding truly effective policies to combat the threat.

An agency that does this will successfully satisfy the economic and psychological self-interest of the people who who work for it. Economically, the bigger the threat the bigger the institution to oppose it. This is true regardless of whether we’re talking about a government agency arguing for a bigger slide of taxpayer revenue or a non-profit appealing for donations. Psychologically, the bigger the threat the easier it is for the people who work in the institution to feel good about themselves and not think too hard about whether or not they are really picking the most effective tools to eliminate whatever they’re supposed to be eliminating. In short: institutions that oppose a thing will gradually come to be hysterical and ineffectual because that’s in the best interest of the people who run those institutions.

This may sound all very hypothetical, so let me give you a specific example: the Southern Poverty Law Center. Politico Magazine recently came out with a very long article titled Has a Civil Rights Stalwart Lost Its Way? which makes a lot of sense when you keep the perils of perverse institutional incentives in mind as you’re reading it. The article points out that the SPLC has “built itself into a civil rights behemoth with a glossy headquarters and a nine-figure endowment, inviting charges that it oversells the threats posed by Klansmen and neo-Nazis to keep donations flowing in from wealthy liberals.”[ref]9-figure means hundreds of millions, by the way, so we’re not talking chump-change here.[/ref] It also notes that the election of Trump–while ostensibly bad for anti-racism efforts in the US–is unquestionably great for the SPLC, “giving the group the kind of potent foil it hasn’t had since the Klan.” So no, this isn’t just hypothetical theorizing. It’s what is happening already, to one of America’s most legendary anti-racism institutions.

The second set of perverse incentives are personal and basically class-based. Both the systematic and implicit definitions of racism evolved on elite college campuses, and the anti-racist theories that are based on these definitions are correspondingly unlikely to successfully reflect the interests and concerns of the genuinely underprivileged. They may be about the underprivileged, but they are adapted to–and serve the interests of–elites.

Consider first the case of a hypothetical young black man with a solidly middle- or upper-class background. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. observed that “the most ironic outcome of the Civil Rights movement has been the creation of a new black middle class which is increasingly separate from the black underclass,” and a 2007 PEW found that nearly 40 percent of blacks felt that “a widening gulf between the values of middle class and poor blacks” which meant that “blacks can no longer be thought of as a single race.” Thus, this young man faces a sense of double alienation: alienation from lower-class blacks and alienation from upper-class whites. Placing emphasis exclusively on the racial component of social analysis obscures the gulf between lower- and upper-class blacks and offers a sense of racial solidarity and wholeness. At the same time, it denies the actual privilege enjoyed by this person (after all, his neighborhood is not crime ridden and his schools are high-functioning) and therefore eases any sense of conflict or guilt at his comparative fortune.

The case is simpler for a hypothetical young white man with a privileged background, but (since this person enjoys even more advantages) the need for some kind of absolution is even more acute. Propounding the new definitions of racism allows low-cost access to that absolution. For an example of how this works, consider how the hilarious blog-turned-book Stuff White People Like discussed white people’s love of “Awareness.”[ref]Note that Stuff White People Like is, according to Wikipedia, “not about the interests of all white people, but rather a stereotype of affluent, environmentally and socially conscious, anti-corporate white North Americans, who typically hold a degree in the liberal arts.”[/ref] Stuff White People Like notes that “an interesting fact about white people is that they firmly believe that all of the world’s problems can be solved through “awareness.” Meaning the process of making other people aware of problems, and then magically someone else like the government will fix it.” The entry goes on: “This belief allows them to feel that sweet self-satisfaction without actually having to solve anything or face any difficult challenges.” Finally:

What makes this even more appealing for white people is that you can raise “awareness” through expensive dinners, parties, marathons, selling t-shirts, fashion shows, concerts, eating at restaurants and bracelets. In other words, white people just have to keep doing stuff they like, EXCEPT now they can feel better about making a difference.

The apotheosis of this awareness-raising fad is the ritual of “privilege-checking” in which whites, men, heterosexuals, and the cisgendered publicly acknowledge their privilege for the sake of feeling good about publicly acknowledging their privilege. In biting commentary for the Daily Beast, John McWhorter noted that:

The White Privilege 101 course seems almost designed to turn black people’s minds from what political activism actually entails. For example, it’s a safe bet that most black people are more interested in there being adequate public transportation from their neighborhood to where they need to work than that white people attend encounter group sessions where they learn how lucky they are to have cars. It’s a safe bet that most black people are more interested in whether their kids learn anything at their school than whether white people are reminded that their kids probably go to a better school.

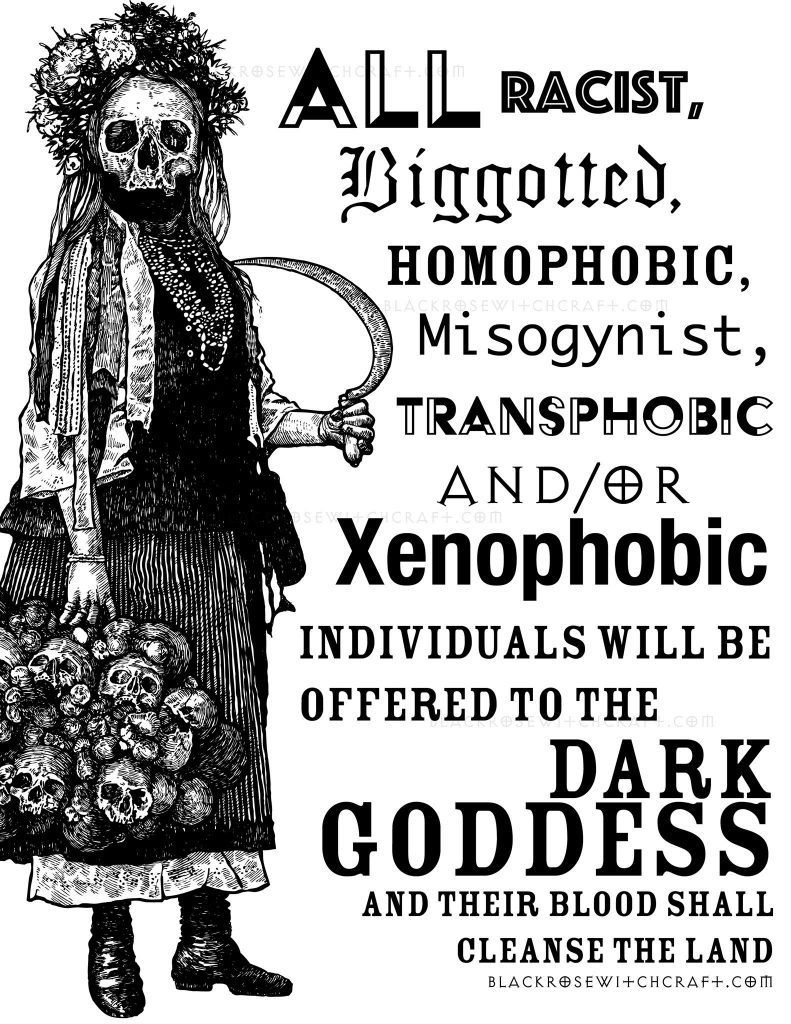

So we’re at a time when the complexity of racial injustice in the United States calls for new and nuanced definitions and theories of racism at precisely the time when–due to the past successes–the temptation to exaggerate racism and ignore effective anti-racism policies is also rising. The result? You might have a Facebook friend who will pontificate about how “everyone is racist” one day, and then post an image like this one the next:

So, you know, “we’re all racist” and also “if you’re racist, you deserve to die.” No mixed messages there, or anything.

Speaking of implicit bias, by the way, the actual results of Project Implicit’s testing are that nearly a third of white people have no racial preference or even a bias in favor of blacks. Once again, this doesn’t prove that racial justice has arrived and we can all go home. That’s absolutely not my point. It’s just another illustration that simplistic narratives about white supremacy don’t work as well in a post-slavery, post-Jim Crow world. The serious problems that remain are not as brutally self-evident as white people explicitly stating that the white race is superior.

Just to toss another complicating factor out there, researchers compared implicit bias to actual outcomes in undergraduate college admissions and found that despite the presence of anti-black implicit bias, the actual results of the admission process were skewed in favor of blacks rather than against them:

When making multiple admissions decisions for an academic honor society, participants from undergraduate and online samples had a more relaxed acceptance criterion for Black than White candidates, even though participants possessed implicit and explicit preferences for Whites over Blacks. This pro-Black criterion bias persisted among subsamples that wanted to be unbiased and believed they were unbiased. It also persisted even when participants were given warning of the bias or incentives to perform accurately.

If implicit bias can coexist with outcomes that are biased in the opposite direction, then what exactly are we measuring when we measure implicit bias, anyway?

I believe that both of the new definitions of racism have merit. The idea that institutional inertia can perpetuate racist outcomes long after the original racial animus has disappeared is reasonable theoretically and certainly seems to explain (in part, at least) the racially unequal outcomes in our criminal justice system. The idea that people divide into tribes and treat the outgroup more poorly–and that racial categories make for particularly potent tribal groups–is equally compelling. But the temptation to over-simplify, exagerate, and then coopt racial analysis for institutional and personal benefit is a genuine threat. As long as it’s possible to cash-in on anti-racism–financially and politically–then our progress towards racial justice will be impeded.

I am, generally speaking, a conservative. I don’t, by and large, share the worldview or policy proscriptions of those on the American left. But I do care about racial justice in the United States. I believe that the current discussion–or lack therefore–is significantly hampered by the temptation to profit from it. And I figure hey: maybe by speaking up I can contribute in a small way to shifting the conversation on race away from the left-right political axis and all the toxicity and perverse incentives that come with it.

“And I figure hey: maybe by speaking up I can contribute in a small way to shifting the conversation on race away from the left-right political axis and all the toxicity and perverse incentives that come with it.”

You’re raising awareness about the evils of the doctrine which leads to people thinking that raising awareness matters? :-)

“The article points out that the SPLC has “built itself into a civil rights behemoth with a glossy headquarters and a nine-figure endowment, inviting charges that it oversells the threats posed by Klansmen and neo-Nazis to keep donations flowing in from wealthy liberals.”3 It also notes that the election of Trump–while ostensibly bad for anti-racism efforts in the US–is unquestionably great for the SPLC, “giving the group the kind of potent foil it hasn’t had since the Klan.'”

You’re following an inference from the SPLC being well-funded to the SPLC overselling the threat. That’s not evidence that there’s an incentive to be hysterical, it relies on that assumption as a premise. As for ineffectual, unless you think the SPLC’s goal should be to swing elections, that seems irrelevant. As evidence for the existence of incentives to be hysterical and ineffectual, this is pretty poor. The hysteria bit I buy independently, because I’ve seen fundraising mailers. But I’ve never seen any evidence that people who work at most nonprofits are more motivated to maintain their power than to fix what the organization is intended to oppose. That strikes me as much like the inference that doctors don’t really want to cure fibromyalgia because they all seem to recommend arduous long-term management rather than simply offering people the pill which cures it.

But even if you were right about everything else you say about the current discourse about race, do you have any ideas about a better way to talk about it? Because, if you’re saying we need to stop doing what we’re doing to combat racism but you don’t have anything you want to substitute, your policy proposals look exactly like the policy proposals of white supremacists. That doesn’t strike me as at all the message you’re intending. One alternative would be to make explicit that you support current efforts to fight racism until we find something better, you’re just trying to encourage finding even more effective solutions ASAP. If you think current efforts to fight racism are worse than doing nothing, that’s not inconceivable, but it seems like you’ll need tremendously persuasive evidence to overcome my Bayesian priors on that, and you’ll want to do a truly heroic job of establishing that you’re not just trying to provide cover for a wickedly racist project.

Kelsey-

Touche.

I do think how we talk about these things really matters, however. What I’m opposed to is the toxicity of victimhood culture. If being a victim is a route to socio-political power, then all discussions of victimhood become hopelessly poisoned.

It’s incredibly naive, in my view, to believe that people don’t respond to incentives. The converse (that people do respond to incentives) is one of the key insights of microeconomic theory and has been validated again and again in a wide range of contexts. The idea that non-profit workers are somehow immune to this universal fact of human nature is the one that requires some strong evidence to accept. All I’m saying is: people are people.

You’re counter-example doesn’t really work, because in addition to the critique of perverse incentives (which is fair) it also supposes the existence of a hypothetical silver-bullet to cure fibromyalgia, which takes us into conspiracy theory territory. Same idea as rumors the GM has a secret engine in their basement that gets 1,000 mpg or whatever.

However, we can easily observe that (1) disease cures that are either patentable or that affect rich people get far more R&D dollars than cures that are not-patentable or that affect poor people and (2) waste, fraud, and abuse in non-profits is endemic.

I think some current efforts do more harm than good, notably the most visible ones. But there’s not one, singular, monolithic group, ideology, or set of practices out there fighting racism. A lot of people are doing good work and making the world a better place. It’s a very specific ideology that I’m opposed to here.

Better ways to talk about it? Yeah. I think that’s easy, at least in theory. Basically: stop demonizing people who depart from a narrow, political orthodoxy. Which is basically the same as saying: stop using race as a partisan tool.

But if you’re also asking about the kinds of policies that I’d support, I have ideas there, too. Especially around the criminal justice system. There are a lot of court findings that either limit our ability to quantify racism and/or provide excessive protections for prosecutors. I definitely have changes I’d like to see there to root out systemic racism in our criminal justice system.

“If being a victim is a route to socio-political power, then all discussions of victimhood become hopelessly poisoned.”

What’s the alternative? If being a victim isn’t a route to enough power to redress grievances, society is systematically unjust. If we refuse to identify victims, how do we seek justice?

“You’re counter-example doesn’t really work, because in addition to the critique of perverse incentives (which is fair) it also supposes the existence of a hypothetical silver-bullet to cure fibromyalgia, which takes us into conspiracy theory territory. ”

That’s my point–people often look at efforts to oppose some social ill–poverty, say, or racism–and claim that, since we’ve spent so much time and money fighting it, but it still exists, that must mean that we’re not really trying. But that requires thinking that there’s some better way, like a magic pill for fixing poverty or racism, rather than that these are problems which we’ll be managing for the foreseeable future no matter how hard we fight them. So people go looking for it–they say, “Hey, we’ve been fighting the war on poverty for fifty years, but people are still poor. Maybe, rather than giving poor people money, we should try a more regressive tax system and supply-side magic will make unskilled labor (to which we have more alternatives than ever before) valuable.”

I’m not saying people don’t respond to incentives, I’m saying they respond most to the incentives which matter most to them, and that the people who go into most helping professions find the success of their endeavors more rewarding than money or power. Doctors who choose to work with patients generally like helping those patients more than doctors who work on developing drugs or basic science. People who choose to work against racism generally enjoy success in that endeavor enough that those rewards swamp the rewards they would get from incubating racism in order to keep their jobs. That’s why the most compelling evidence for the influence of incentives on helping professions comes from cases which aren’t really in them at all, like the business school graduates who decide which research to fund, or frauds. If you’re going to look at incentives, you have to accept that not everyone values outcomes the same way, and the large majority of the people who think privilege and victimhood are worth noting are completely sincere and not motivated to say so by money.

An aside: I’m deeply troubled by the consequences of this for some professions, notably ICE/Border Patrol and various forms of financial advice. I don’t see how you avoid attracting brutal, xenophobic racists at an unusually high rate to the first, and people who care more about money than integrity to the second.

“Basically: stop demonizing people who depart from a narrow, political orthodoxy. ”

If you’re proposing plausible solutions which take the issues of systemic and subconscious racism seriously, I’d be shocked if you experience that. If what you’re focusing on is opposing the political left and all of the most visible forms of fighting racism, the polarization is coming from you as much as anyone. When you think about the post above, don’t you see it as demonizing leftist anti-racists (including calling them hysterical and ineffectual)? That kills me, because your thoughts about the criminal justice system sound fascinating. I’d love to hear more about that. Among other things, I’m really interested to know how you’d like to both quantify racism and also avoid supporting a culture of victimhood.

I guess it seems to me like I’ve seen two responses to excess polarization and demonization. One is to deride the other side for their contributions to it, and the other is to try to work together on pragmatic solutions acceptable to both sides. I’ve never seen the first one work–it just contributes to the problem. You sound like you have a path available to do the second. Why not go for it?