If you’re into a lot of graphs and number crunching, read on. If you’re not, here’s the bottom line: compared to pro-life states, pro-choice states have more insurance coverage of contraception yet have roughly the same rates of unintended pregnancies and much higher rates of abortion.

In early 2015 the Washington Post published the article “States that are more opposed to abortion rights have fewer abortions — but not fewer unintended pregnancies.” Author Aaron Blake notes:

In fact, some of the states that oppose abortion the most also have some of the highest rates of unintended pregnancies — particularly in the South. And on average, the states that favor abortion rights the most have slightly lower levels of unintended pregnancies.

Blake elaborates:

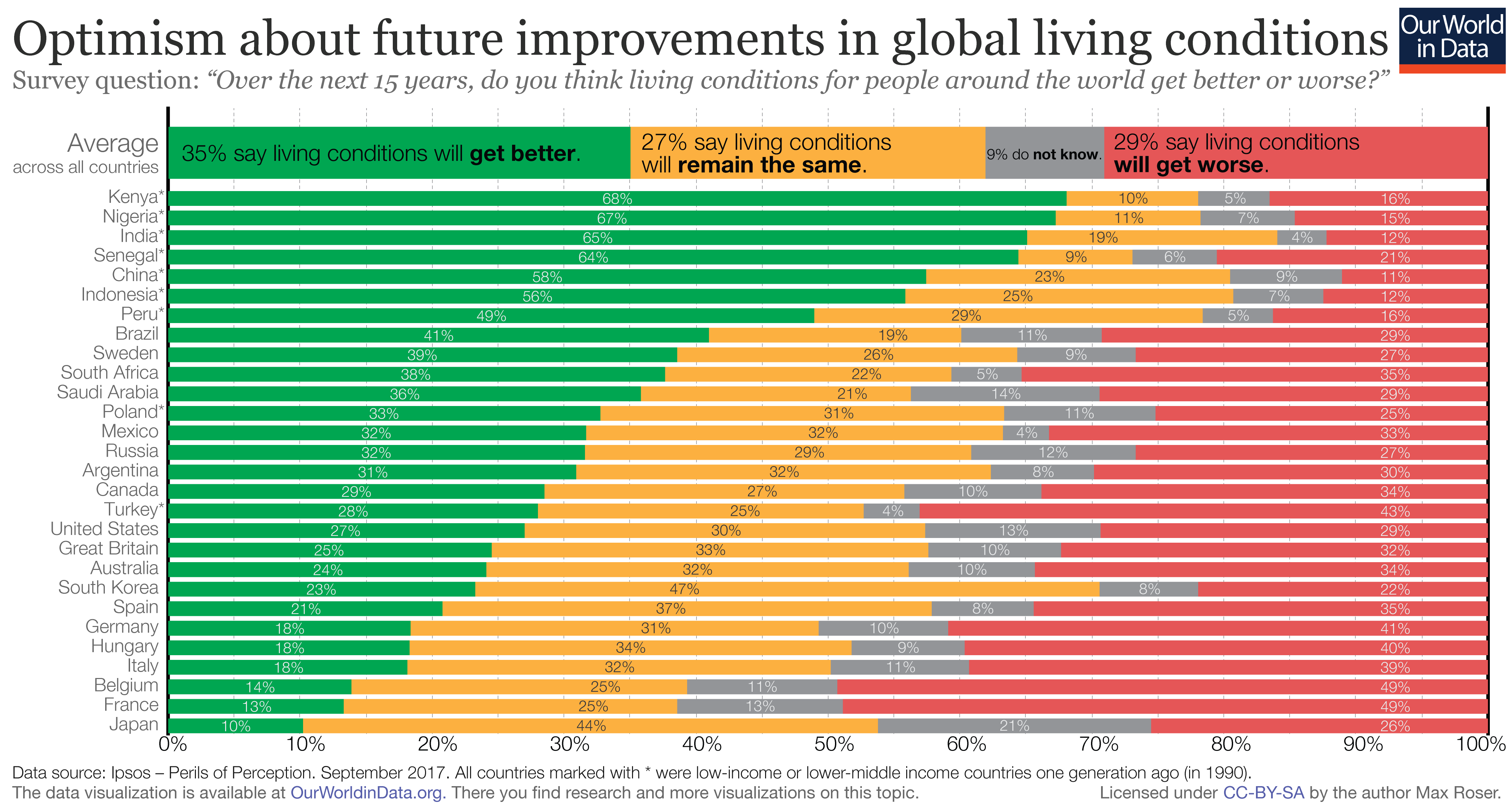

Mississippi, for instance, is the state that opposes abortion rights the most, according to Pew, with 64 percent generally opposing the procedure. It is also the state with the most unintended pregnancies, at 62 percent of all pregnancies, according to Guttmacher. After accounting for fetal loss, about two-thirds of those unintended pregnancies were brought to term.

By contrast, Massachusetts is one of the most pro-abortion-rights states, with just 28 percent of people opposing the procedure. But it’s also on the low end as far as the percentage of unintended pregnancies (44 percent). Far fewer — 43 percent — of those pregnancies were brought to term.

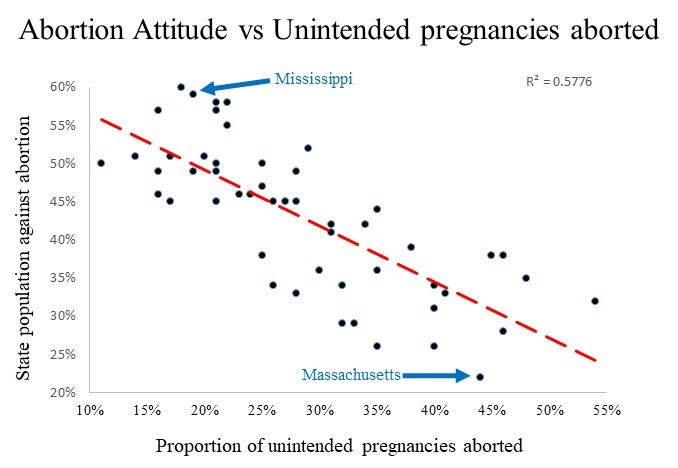

In both his article’s title and text Blake seems to imply a correlation between anti-abortion attitude and higher proportions of unintended pregnancies. This implication seems plausible because Blake focuses on only two data points among all 50 (51 if you count the District of Columbia). In fact if you plot the two states Blake highlights–Mississippi and Massachusetts–you get this graph:

And yet the only time Blake addresses trends across the whole country, he admits:

On average in the 10 states that oppose abortion the most, 51 percent of pregnancies are unintended. In the top 10 states that most favor abortion rights, it’s 50 percent.[ref]From here on I refer to states that oppose abortion as “pro-life states” and states that favor abortion rights as “pro-choice states.”[/ref]

In other words, the two groups hardly differ at all. Out of curiosity I dug up the numbers used to measure unintended pregnancy (from Guttmacher) and abortion opposition (from Pew Research Center)[ref]I found slightly different data than the numbers Blake cites. I suspect we’re drawing from Pew Research data sets in different years[/ref]. Instead of comparing only the 10 most pro-life states to the 10 most pro-choice states, I looked at all 50 states (and DC). Here’s what it looks like when you don’t cherry pick:

So when you look at the whole data set (instead of only Mississippi compared to Massachussetts, or only the top 10 pro-life states compared to the top 10 pro-choice ones), there appears to be no relationship at all between views on abortion and unintended pregnancy.[ref]Note the above graphs look at the proportion of pregnancies that were unintended, not the proportion of women with unintended pregnancies (called the “unintended pregnancy rate”). However I checked that data too (it’s available in the same Guttmacher link above), and when you compare abortion sentiment to unintended pregnancy rate, the result is basically the same, with an R^2 of 0.0011.[/ref]

I found this lack of correlation interesting. Pro-choicers often claim the best way to decrease abortion is not through outlawing abortion but through better access to contraception. If that theory is true, I would expect the states most open to abortion to also have lower unintended pregnancy rates, because (1) pro-choice states are more left-leaning, (2) left-leaning states are more likely to support better access to contraception, and (3) better access to contraception is supposed to decrease unintended pregnancies and thus abortion rates.

And yet the above graphic suggests that pro-choice states have no lower unintended pregnancy rates than pro-life states. Why is that? A few possibilities jump to mind:

- Pro-choice states don’t necessarily have better access to contraception than pro-life states.

- Pro-choice states do have better access to contraception, but that doesn’t actually decrease unintended pregnancy rates (and thus abortion rates).

- Pro-choice states have better access to contraception, and better access does decrease unintended pregancy rates, but some other factor in those states increases unintended pregnancy rates, thus cancelling the contraception effect.

I decided to dig a bit more. I used the same Guttmacher and Pew Research data linked above for unintended pregnancy info and state attitudes about abortion. To measure state access to contraception I used data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, which outlines which states require coverage of prescription contraception, related outpatient services, and no cost contraception coverage. I also looked at data collected by the National Women’s Law Center regarding which states have contraceptive equity laws (i.e. laws that require insurance plans to cover a full range of contraceptives for women). I assigned each state a contraception score by giving 1 point for each law or coverage requirement, with a maximum of 4 points.

Pro-choice states have more contraception access.

States with zero contraception coverage requirements had an average of 49% of their populations say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. States with 2 or 3 contraception coverage requirements had 41% and 38% say abortion should generally be illegal. And states with all 4 contraception coverage requirements had only 32% of their populations say abortion should be illegal all or most of the time.

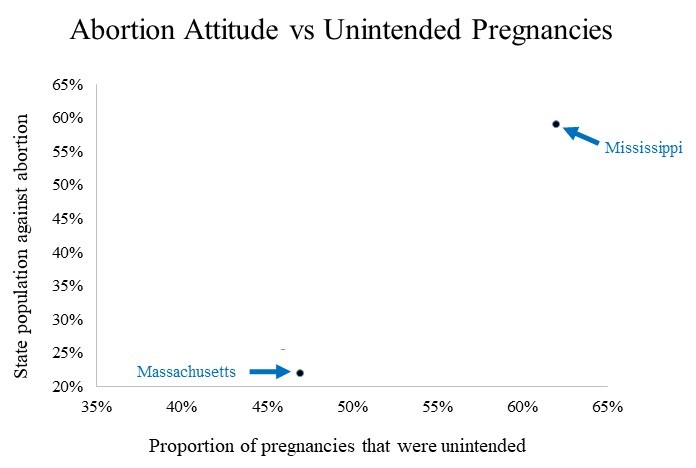

States with more contraception access don’t see lower unintended pregnancy rates.

I then averaged the unintended pregnancy rates for states based on their contraception score and it looked like this:

The states with the most contraception coverage requirements had the lowest unintended pregnancy rate at 44 per 1,000 women age 15-44. The states with zero contraception coverage requirements had the next lowest rate at 45.95. The states in between–with 2 or 3 contraception coverage requirements–had higher unintended pregnancy rates at 50.25 and 49.08 respectively. In other words there’s no obvious relationship between states’ contraception coverage requirements and their unintended pregnancy rates.

States with less access to contraception have lower abortion rates.

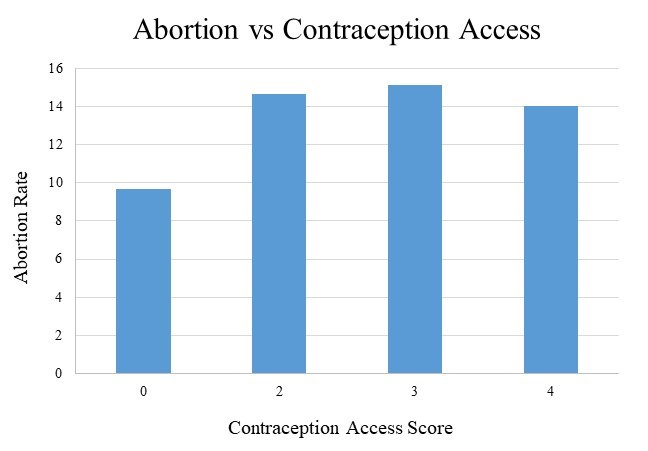

Since I already had the data handy I also compared state contraception access to abortion rates:

The states with zero contraception coverage requirements had the lowest abortion rates at 9.68 abortions per 1,000 women age 15-44. States with 2, 3, and 4 contraception coverage requirements had rates of 14.58, 15.14, and 14.00, respectively.

This result could imply that contraception access actually increases abortion rates, and many pro-lifers try to make that claim. Their theory is that whenever you have a desirable but risky action (sex), the more you lower the risk the more often people will take that action. If people think the risk is lowered more than is actually the case (e.g. if the contraception they’re using or the way they’re using it isn’t as effective as they think), then they may be actually increasing their risk exposure by taking a risky action more often without proportionally decreasing the risk in each instance. This theory is plausible because states with more contraception access do not have lower unintended pregnancy rates. Perhaps these populations lower the risk of a given instance of sex by using contraception but increase their overall risk exposure by having sex more often without using contraception consistently or correctly.

Pro-choice states have higher abortion rates.

Alternatively, perhaps the high contraceptive states have higher abortion rates simply because they are more pro-choice states. Given roughly equal unintended pregnancy rates, we’d expect the populations that support abortion to have higher abortion rates, and the data bears that out.

This trend may be due to social influences. It’s possible that women experiencing unintended pregnancies in more pro-life states experience more pressure not to abort, more encouragement and support to carry their pregnancies, or both, and that women in more pro-choice states experience the opposite. It’s hard to measure how much social pressures influence these decisions.

Either way, though, there’s little doubt that legal restrictions also influence women’s choices. To measure state-by-state legal restrictions, I again turned to Guttmacher. I assigned each state points based on whether they had the following restrictions in place and, if so, to what degree. The potential restrictions include:

- Whether the abortion must be performed by a licensed physician

- Whether and when the abortion must be performed at a hospital

- Whether and when a second physician must be present

- Whether and when abortion is prohibited (except life or health of the mother)

- Whether partial birth abortion is banned

- Whether public funding can be used for most abortions or very few abortions

- Whether private insurance has to cover abortions

- Whether individuals can refuse to participate in abortions

- Whether and when institutions can refuse to participate in abortions

- Whether there is mandated counseling regarding either an abortion breast cancer link, fetal pain, negative psychological effects, or any combination of those factors

- Whether and how long mandatory waiting must be

- Whether parents have to be notified or have to consent to their kids’ abortions

States with more legal restrictions garnered more points with a maximum possible 12 points. Unsurprisingly, there was an inverse correlation between the number of abortion restrictions and the proportion of unintended pregnancies aborted.

Contraception is not a panacea for abortion.

Pro-choice people repeatedly claim that if we truly care about lowering abortion rates we should support pro-choice policies and politicians who promote contraception access. As I’ve written about previously, this theory isn’t backed by the evidence. There’s some research to suggest contraception access–especially access to long acting reversible contraception–can help, but so far the evidence I’ve found continues to show that the abortion rate decreases more when there are more abortion restrictions than it does when there is more access to contraception.