From my BYU Studies Quarterly article:

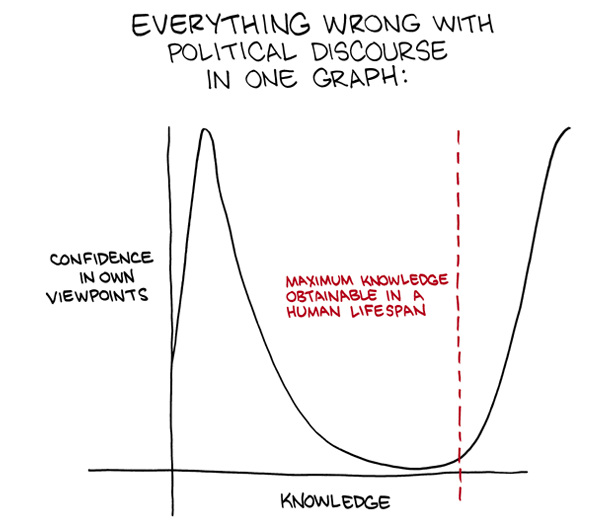

A particularly interesting aspect of public attitudes toward immigration is that of political ignorance. Multiple studies have shown that political ignorance is rampant among average voters, and this holds true when it comes to immigration policy. As legal scholar Ilya Somin explains, “Immigration restriction . . . is one that has long-standing associations with political ignorance. In both the United States and Europe,survey data suggest that it is strongly correlated with overestimation of the proportion of immigrants in the population, lack of sophistication in making judgments about the economic costs and benefits of immigration, and general xenophobic attitudes toward foreigners. By contrast, studies show that there is little correlation between opposition to immigration and exposure to labor market competition from recent immigrants.” One pair of economists found that those voting to leave the European Union in the Brexit referendum, who were motivated largely by a desire to restrict immigration, “were overwhelmingly more likely to live in areas with very low levels of migration.” Similarly, voters who supported Donald Trump during the US election were more likely to oppose liberalizing immigration laws (even compared to other Republicans), but least likely to live in racially diverse neighborhoods. In short, both political ignorance and lack of interaction with foreigners tend to inflame anti-immigration sentiments. These sentiments are what George Mason University economist Bryan Caplan refers to as antiforeign bias: “a tendency to underestimate the economic benefits of interaction with foreigners.” In fact, economists take nearly the opposite view from the general public on immigration (pgs. 80-82).

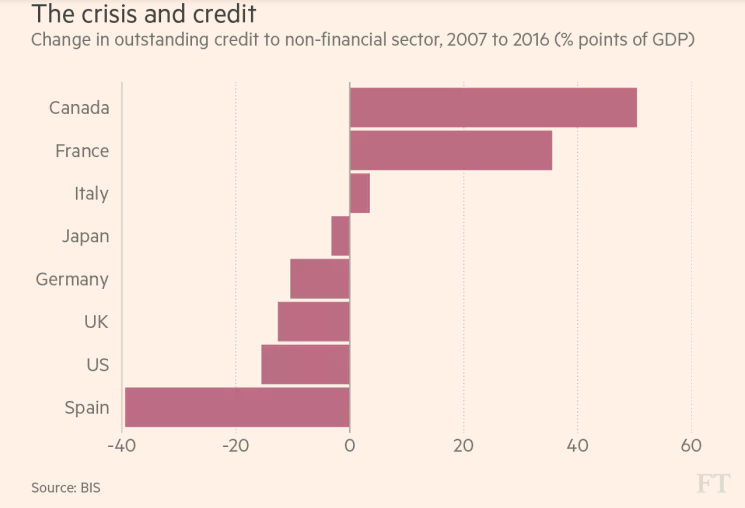

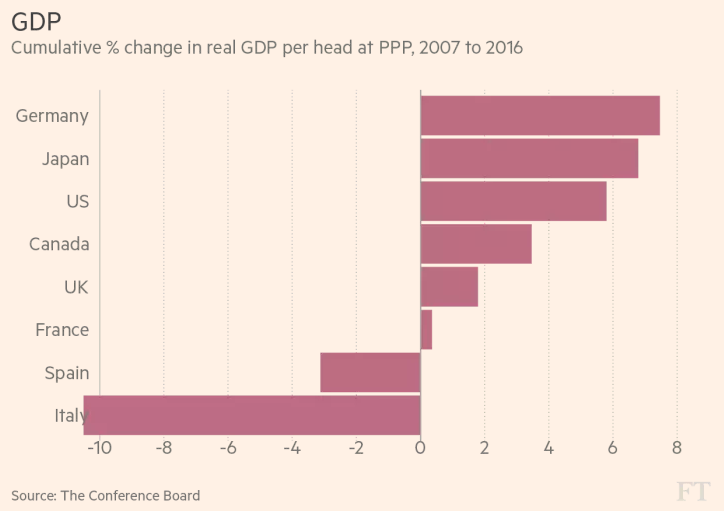

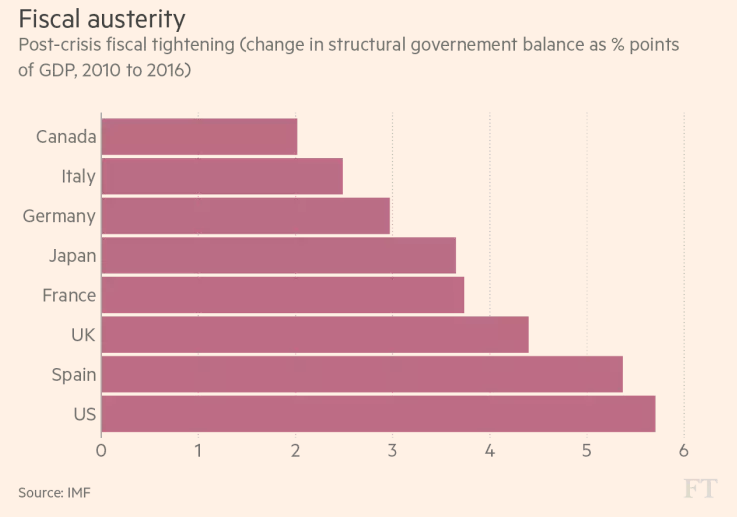

The evidence we uncover shows that financial crises put a strain on modern democracies. The typical political reaction is as follows: votes for far-right parties increase strongly, government majorities shrink, the fractionalization of parliaments rises and the overall number of parties represented in parliament jumps. These developments likely hinder crisis resolution and contribute to political gridlock. The resulting policy uncertainty may contribute to the much debated slow economic recoveries from financial crises. Financial crises are politically disruptive, even when compared to other economic crises. Indeed, we find no (or only slight) political effects of normal recessions and different responses in severe crises not involving a financial crash. In the latter, right wing votes do not increase as strongly and people rally behind the government. In the light of modern history, political radicalization, declining government majorities and increasing street protests appear to be the hallmark of financial crises. As a consequence, regulators and central bankers carry a big responsibility for political stability when overseeing financial markets. Preventing financial crises also means reducing the probability of a political disaster (pg. 245).

that financial crises of the past 30 years have been a catalyst of rightwing populist politics. Many of the now-prominent right-wing populist parties in Europe, such as the Lega Nord in Italy, the Alternative for Germany, the Norwegian Progress Party or the Finn’s Party are “children of financial crises”, having made their breakthrough in national politics in the years following a financial crash. We also find that the 2008 crisis triggered a wave of governments in which right-wing populists gained power, often as a coalition partner. As discussed, the crisis is just one of many potential factors explaining the recent successes of right-wing populism in Europe and beyond. Other drivers such as “cultural backlash”, the impact of globalization, rising inequality, and the refugee crisis of 2015 surely played a critical role too. However, “the rise of the right” in Europe since 2008 cannot be fully understood without considering the impact of the 2008 and 2011/2012 financial crises…A first potential explanation is that financial crises are perceived as inexcusable events that result from a failure of policies and regulation, rather than from an external shock. This leads to distrust in government and mainstream politics. Secondly, financial crises typically trigger creditor-debtor conflicts (Mian et al. 2014) and a rise in income and wealth inequality (Atkinson and Morelli 2010, 2011) to levels not observed in normal recessions. Thirdly, we know that financial crashes often involve large-scale bank bailouts and these are highly controversial and unpopular (e.g., Broz 2005). Such bail-out initiatives give traction to extremist ideas at the political fringe. In this environment of distrust, uncertainty and dissatisfaction, right-wing populists have learned to gain votes by offering seemingly simple solutions to complex problems, and by attributing blame to minorities or foreigners (pg. 8).

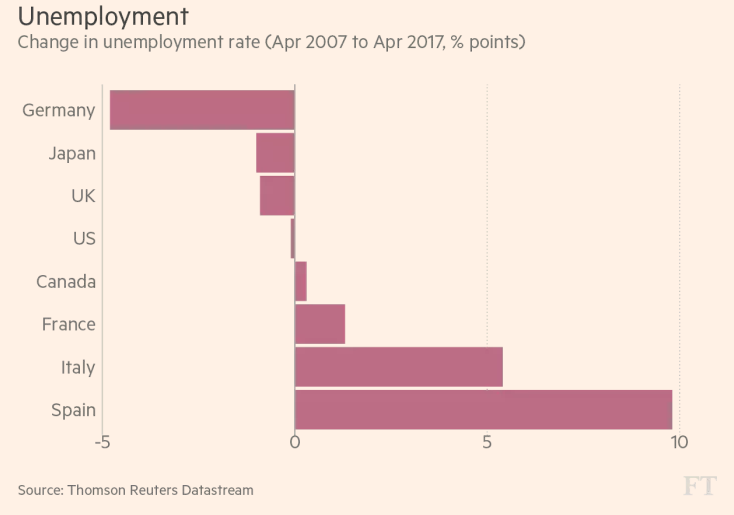

a strong correlation between rising regional unemployment and voting for non-mainstream and especially populist parties. A one percentage point increase in unemployment is associated with a one percentage point increase in the populist vote. The association is especially strong in the south, where voters turn mostly to radical-left parties. In the north increases in regional unemployment are correlated with a rise in far-right party vote. This pattern is also present in eastern Europe, where people are moving towards xenophobic, anti-European parties. These associations do not necessarily imply causality. To advance on causality we associate voting patterns to the component of changes in unemployment stemming from the pre-crisis share of construction (which is strongly related to falling unemployment pre-2007 and rising unemployment post-2008). This approach also yields a strong correlation between the recent rise of the populist vote and industrial specialization–driven unemployment. We then examine the role of the crisis on the Brexit vote across the UK’s 379 electoral districts. In line with the European-wide results, [the data] show that the increases in regional unemployment before the referendum (2007–15) are strong predictors of the Brexit vote, while the level of unemployment is not much related to Brexit. We then study the evolution of trust, political beliefs and attitudes before and after the 2007–10 crisis and examine whether swings in unemployment are related to changing ideology. We use individual-level data on Europeans’ beliefs and attitudes from the European Social Survey that covers the period 2000–2014. [The data] show that increases in regional unemployment have resulted in a deterioration of trust towards national and European political institutions.

Valerie M. Hudson, Bonnie Ballif-Spanvill, Mary Caprioli, Chad Emmett, Sex & World Peace (Columbia University Press, 2012): “Sex and World Peace unsettles a variety of assumptions in political and security discourse, demonstrating that the security of women is a vital factor in the security of the state and its incidence of conflict and war. The authors compare micro-level gender violence and macro-level state peacefulness in global settings, supporting their findings with detailed analyses and color maps. Harnessing an immense amount of data, they call attention to discrepancies between national laws protecting women and the enforcement of those laws, and they note the adverse effects on state security of abnormal sex ratios favoring males, the practice of polygamy, and inequitable realities in family law, among other gendered aggressions. The authors find that the treatment of women informs human interaction at all levels of society. Their research challenges conventional definitions of security and democracy and shows that the treatment of gender, played out on the world stage, informs the true clash of civilizations. In terms of resolving these injustices, the authors examine top-down and bottom-up approaches to healing wounds of violence against women, as well as ways to rectify inequalities in family law and the lack of parity in decision-making councils. Emphasizing the importance of an R2PW, or state responsibility to protect women, they mount a solid campaign against women’s systemic insecurity, which effectively unravels the security of all” (

Valerie M. Hudson, Bonnie Ballif-Spanvill, Mary Caprioli, Chad Emmett, Sex & World Peace (Columbia University Press, 2012): “Sex and World Peace unsettles a variety of assumptions in political and security discourse, demonstrating that the security of women is a vital factor in the security of the state and its incidence of conflict and war. The authors compare micro-level gender violence and macro-level state peacefulness in global settings, supporting their findings with detailed analyses and color maps. Harnessing an immense amount of data, they call attention to discrepancies between national laws protecting women and the enforcement of those laws, and they note the adverse effects on state security of abnormal sex ratios favoring males, the practice of polygamy, and inequitable realities in family law, among other gendered aggressions. The authors find that the treatment of women informs human interaction at all levels of society. Their research challenges conventional definitions of security and democracy and shows that the treatment of gender, played out on the world stage, informs the true clash of civilizations. In terms of resolving these injustices, the authors examine top-down and bottom-up approaches to healing wounds of violence against women, as well as ways to rectify inequalities in family law and the lack of parity in decision-making councils. Emphasizing the importance of an R2PW, or state responsibility to protect women, they mount a solid campaign against women’s systemic insecurity, which effectively unravels the security of all” ( Eric Nelson, The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought (Harvard University Press, 2010): “According to a commonplace narrative, the rise of modern political thought in the West resulted from secularization—the exclusion of religious arguments from political discourse. But in this pathbreaking work Eric Nelson argues that this familiar story is wrong. Instead, he contends, political thought in early-modern Europe became less, not more, secular with time, and it was the Christian encounter with Hebrew sources that provoked this radical transformation. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Christian scholars began to regard the Hebrew Bible as a political constitution designed by God for the children of Israel. Newly available rabbinic materials became authoritative guides to the institutions and practices of the perfect republic. This thinking resulted in a sweeping reorientation of political commitments. In the book’s central chapters Nelson identifies three transformative claims introduced into European political theory by the Hebrew revival: the argument that republics are the only legitimate regimes; the idea that the state should coercively maintain an egalitarian distribution of property; and the belief that a godly republic would tolerate religious diversity. One major consequence of Nelson’s work is that the revolutionary politics of John Milton, James Harrington, and Thomas Hobbes appear in a brand-new light. Nelson demonstrates that central features of modern political thought emerged from an attempt to emulate a constitution designed by God. This paradox, a reminder that while we may live in a secular age, we owe our politics to an age of religious fervor, in turn illuminates fault lines in contemporary political discourse” (

Eric Nelson, The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought (Harvard University Press, 2010): “According to a commonplace narrative, the rise of modern political thought in the West resulted from secularization—the exclusion of religious arguments from political discourse. But in this pathbreaking work Eric Nelson argues that this familiar story is wrong. Instead, he contends, political thought in early-modern Europe became less, not more, secular with time, and it was the Christian encounter with Hebrew sources that provoked this radical transformation. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Christian scholars began to regard the Hebrew Bible as a political constitution designed by God for the children of Israel. Newly available rabbinic materials became authoritative guides to the institutions and practices of the perfect republic. This thinking resulted in a sweeping reorientation of political commitments. In the book’s central chapters Nelson identifies three transformative claims introduced into European political theory by the Hebrew revival: the argument that republics are the only legitimate regimes; the idea that the state should coercively maintain an egalitarian distribution of property; and the belief that a godly republic would tolerate religious diversity. One major consequence of Nelson’s work is that the revolutionary politics of John Milton, James Harrington, and Thomas Hobbes appear in a brand-new light. Nelson demonstrates that central features of modern political thought emerged from an attempt to emulate a constitution designed by God. This paradox, a reminder that while we may live in a secular age, we owe our politics to an age of religious fervor, in turn illuminates fault lines in contemporary political discourse” ( Hans Rosling with Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Ronnlund, Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World–and Why Things Are Better Than You Think (Flatiron Books, 2018): “When asked simple questions about global trends―what percentage of the world’s population live in poverty; why the world’s population is increasing; how many girls finish school―we systematically get the answers wrong. So wrong that a chimpanzee choosing answers at random will consistently outguess teachers, journalists, Nobel laureates, and investment bankers. In Factfulness, Professor of International Health and global TED phenomenon Hans Rosling, together with his two long-time collaborators, Anna and Ola, offers a radical new explanation of why this happens. They reveal the ten instincts that distort our perspective―from our tendency to divide the world into two camps (usually some version of us and them) to the way we consume media (where fear rules) to how we perceive progress (believing that most things are getting worse). Our problem is that we don’t know what we don’t know, and even our guesses are informed by unconscious and predictable biases. It turns out that the world, for all its imperfections, is in a much better state than we might think. That doesn’t mean there aren’t real concerns. But when we worry about everything all the time instead of embracing a worldview based on facts, we can lose our ability to focus on the things that threaten us most. Inspiring and revelatory, filled with lively anecdotes and moving stories, Factfulness is an urgent and essential book that will change the way you see the world and empower you to respond to the crises and opportunities of the future” (

Hans Rosling with Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Ronnlund, Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World–and Why Things Are Better Than You Think (Flatiron Books, 2018): “When asked simple questions about global trends―what percentage of the world’s population live in poverty; why the world’s population is increasing; how many girls finish school―we systematically get the answers wrong. So wrong that a chimpanzee choosing answers at random will consistently outguess teachers, journalists, Nobel laureates, and investment bankers. In Factfulness, Professor of International Health and global TED phenomenon Hans Rosling, together with his two long-time collaborators, Anna and Ola, offers a radical new explanation of why this happens. They reveal the ten instincts that distort our perspective―from our tendency to divide the world into two camps (usually some version of us and them) to the way we consume media (where fear rules) to how we perceive progress (believing that most things are getting worse). Our problem is that we don’t know what we don’t know, and even our guesses are informed by unconscious and predictable biases. It turns out that the world, for all its imperfections, is in a much better state than we might think. That doesn’t mean there aren’t real concerns. But when we worry about everything all the time instead of embracing a worldview based on facts, we can lose our ability to focus on the things that threaten us most. Inspiring and revelatory, filled with lively anecdotes and moving stories, Factfulness is an urgent and essential book that will change the way you see the world and empower you to respond to the crises and opportunities of the future” ( N.T. Wright, Paul: A Biography (HarperOne, 2018): “In this definitive biography, renowned Bible scholar, Anglican bishop, and bestselling author N. T. Wright offers a radical look at the apostle Paul, illuminating the humanity and remarkable achievements of this intellectual who invented Christian theology—transforming a faith and changing the world. For centuries, Paul, the apostle who “saw the light on the Road to Damascus” and made a miraculous conversion from zealous Pharisee persecutor to devoted follower of Christ, has been one of the church’s most widely cited saints. While his influence on Christianity has been profound, N. T. Wright argues that Bible scholars and pastors have focused so much attention on Paul’s letters and theology that they have too often overlooked the essence of the man’s life and the extreme unlikelihood of what he achieved. To Wright, “The problem is that Paul is central to any understanding of earliest Christianity, yet Paul was a Jew; for many generations Christians of all kinds have struggled to put this together.” Wright contends that our knowledge of Paul and appreciation for his legacy cannot be complete without an understanding of his Jewish heritage. Giving us a thoughtful, in-depth exploration of the human and intellectual drama that shaped Paul, Wright provides greater clarity of the apostle’s writings, thoughts, and ideas and helps us see them in a fresh, innovative way. Paul is a compelling modern biography that reveals the apostle’s greater role in Christian history—as an inventor of new paradigms for how we understand Jesus and what he accomplished—and celebrates his stature as one of the most effective and influential intellectuals in human history” (

N.T. Wright, Paul: A Biography (HarperOne, 2018): “In this definitive biography, renowned Bible scholar, Anglican bishop, and bestselling author N. T. Wright offers a radical look at the apostle Paul, illuminating the humanity and remarkable achievements of this intellectual who invented Christian theology—transforming a faith and changing the world. For centuries, Paul, the apostle who “saw the light on the Road to Damascus” and made a miraculous conversion from zealous Pharisee persecutor to devoted follower of Christ, has been one of the church’s most widely cited saints. While his influence on Christianity has been profound, N. T. Wright argues that Bible scholars and pastors have focused so much attention on Paul’s letters and theology that they have too often overlooked the essence of the man’s life and the extreme unlikelihood of what he achieved. To Wright, “The problem is that Paul is central to any understanding of earliest Christianity, yet Paul was a Jew; for many generations Christians of all kinds have struggled to put this together.” Wright contends that our knowledge of Paul and appreciation for his legacy cannot be complete without an understanding of his Jewish heritage. Giving us a thoughtful, in-depth exploration of the human and intellectual drama that shaped Paul, Wright provides greater clarity of the apostle’s writings, thoughts, and ideas and helps us see them in a fresh, innovative way. Paul is a compelling modern biography that reveals the apostle’s greater role in Christian history—as an inventor of new paradigms for how we understand Jesus and what he accomplished—and celebrates his stature as one of the most effective and influential intellectuals in human history” ( Gregory A. Boyd, Cross Vision: How the Crucifixion of Jesus Makes Sense of Old Testament Violence (Fortress Press, 2017): “The Old Testament God of wrath and violence versus the New Testament God of love and peace it’s a difference that has troubled Christians since the first century. Now, with the sensitivity of a pastor and the intellect of a theologian, Gregory A. Boyd proposes the “cruciform hermeneutic,” a way to read the Old Testament portraits of God through the lens of Jesus’ crucifixion. In Cross Vision, Boyd follows up on his epic and groundbreaking study, The Crucifixion of the Warrior God. He shows how the death and resurrection of Jesus reframes the troubling violence of the Old Testament, how all of Scripture reveals God’s self-sacrificial love, and, most importantly, how we can follow Jesus’ example of peace” (

Gregory A. Boyd, Cross Vision: How the Crucifixion of Jesus Makes Sense of Old Testament Violence (Fortress Press, 2017): “The Old Testament God of wrath and violence versus the New Testament God of love and peace it’s a difference that has troubled Christians since the first century. Now, with the sensitivity of a pastor and the intellect of a theologian, Gregory A. Boyd proposes the “cruciform hermeneutic,” a way to read the Old Testament portraits of God through the lens of Jesus’ crucifixion. In Cross Vision, Boyd follows up on his epic and groundbreaking study, The Crucifixion of the Warrior God. He shows how the death and resurrection of Jesus reframes the troubling violence of the Old Testament, how all of Scripture reveals God’s self-sacrificial love, and, most importantly, how we can follow Jesus’ example of peace” (