The question is cheeky, but appropriate given how “check your privilege” is all the rage. A new working paper suggests that high unemployment rates are actually found in wealthy countries rather than poorer ones. The researchers summarize,

[C]laims about unemployment in poorer countries are all over the map, with some studies finding that the highest unemployment rates in the world are in Sub-Saharan Africa, at around 30% per year (World Bank 2004), while others posit that unemployment is almost non-existent in developing countries, since people there are too poor to have the luxury of not working (Fields 2004, Squire 1981).

In our paper (Feng et al. 2018), we contribute to the study of unemployment by building a data set of average unemployment rates covering 84 countries of all income levels. To address the issue of data comparability, we intentionally bypass existing data banks, such as those of the ILO, and build our own measures of unemployment from the ground up using household survey data. We draw on 199 nationally representative household surveys conducted in various recent years (but mostly between 2000 and 2010). Importantly, our data cover not just the rich countries of the world, but many poor nations, including a dozen from sub-Saharan Africa and many more from the middle of the world income distribution.

…We define work as wage employment, self-employment, and unpaid work in a family farm or business. We exclude those doing home production of services like cooking, cleaning, and childcare. Our search measures cover job search activity in some recent period, like the last week (in our preferred metrics). We compute unemployment rates in each survey as the number of adults not working but searching for work / (number working + those not working and searching). We then average over all surveys for each county in our data.

What we find is that average unemployment rates are in fact substantially lower in poor countries than in rich countries. In the poorest quartile of the world income distribution, unemployment averages around 2.5%, while in the richest quartile, around 8% of the labour force is unemployed on average. Interestingly, we find that the higher unemployment rates of richer economies hold for workers of all ages, for men and women separately, and within both urban and rural areas. Thus, our data suggest that unemployment is largely a rich-country phenomenon, rather than a feature of underdevelopment.

Why is this the case?

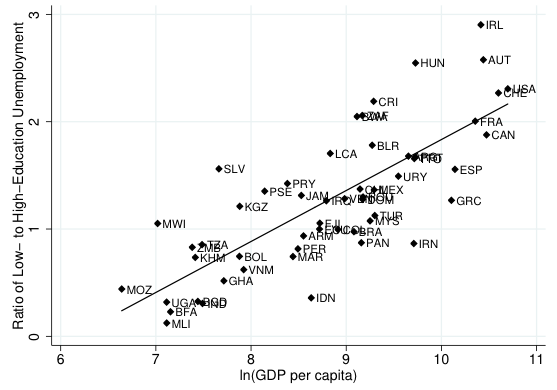

The figure below plots the ratio of unemployment for the low educated to that of the high educated against the log of GDP per capita. In the poorest countries, this ratio is below one, meaning that the low educated are less likely to be unemployed than the high educated. The exact opposite is true of the richest countries, all of whom have ratios above one. For instance, in the US, the ratio is 2.3, meaning that those without high school education are more than twice as likely to unemployed as those that finished high school (or went on to college or beyond). Whereas one might have thought this pattern is a universal feature of labour market outcomes, our data show that unemployment concentrated among the less educated is actually confined to richer economies.

The authors explain,

Countries differ only by their productivity in the modern sector, with the traditional sector offering the same (low) level of output per worker in all countries. This assumption is central to our analysis and based on the emerging consensus that cross-country productivity differences are skill-biased, rather than affecting unskilled and skilled tasks and workers equally (Caselli and Coleman 2006, Malmberg 2016).

The model predicts that in countries with low modern-sector productivity levels, the bulk of the workforce sorts into the traditional sector. Only workers with the highest skill levels choose the modern sector. Then, as modern-sector productivity rises – our proxy for ‘development’ – more and more lower skilled workers are drawn into the modern sector. This raises overall unemployment, as more workers now search for jobs, with some of them being unemployed each period in equilibrium. As in the data, our model predicts that development also brings a rise in the ratio of unemployment for the less- to more-skilled. The reason is most of the higher skilled workers are already in the modern sector and searching for wage jobs in poor economies. As modern-sector productivity grows, it is the less skilled workers that switch sectors, and their unemployment rate rises faster as a result.

They conclude,

Our research suggests that unemployment is largely a feature of advanced economies. In poor countries, only the most skilled workers search for wage jobs, while most of the less skilled workers select into traditional self-employment activities. Thus, few workers in poor economies are actually unemployed in practice. In advanced economies, the modern wage-paying sectors have relatively high productivity levels and employ the bulk of the labour force. As a consequence, as modern firms and positions come and go, workers are occasionally cast into unemployment. While unemployment per se is undesirable, the high underlying productivity level of the modern sector is not.

Paul Krugman once famously said, “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”[ref]The Age of Diminished Expectations: U.S. Economic Policy in the 1990s, 3rd ed., pg. 11.[/ref] Harvard’s Greg Mankiw writes, “Almost all variation in living standards is attributable to differences in countries’ productivity[.]”[ref]Principles of Economics, 7th ed., pg. 13.[/ref] This study demonstrates at least two important points:

- Employed =/= Productive

- Jobs =/= Wealth

America should abolish prisons. Perhaps not all of them, but very close to it.

America should abolish prisons. Perhaps not all of them, but very close to it.

Lawrence M. Krauss, A Universe From Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing (Free Press, 2012): “Bestselling author and acclaimed physicist Lawrence Krauss offers a paradigm-shifting view of how everything that exists came to be in the first place. “Where did the universe come from? What was there before it? What will the future bring? And finally, why is there something rather than nothing?” One of the few prominent scientists today to have crossed the chasm between science and popular culture, Krauss describes the staggeringly beautiful experimental observations and mind-bending new theories that demonstrate not only can something arise from nothing, something will always arise from nothing. With a new preface about the significance of the discovery of the Higgs particle, A Universe from Nothing uses Krauss’s characteristic wry humor and wonderfully clear explanations to take us back to the beginning of the beginning, presenting the most recent evidence for how our universe evolved—and the implications for how it’s going to end. Provocative, challenging, and delightfully readable, this is a game-changing look at the most basic underpinning of existence and a powerful antidote to outmoded philosophical, religious, and scientific thinking” (

Lawrence M. Krauss, A Universe From Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing (Free Press, 2012): “Bestselling author and acclaimed physicist Lawrence Krauss offers a paradigm-shifting view of how everything that exists came to be in the first place. “Where did the universe come from? What was there before it? What will the future bring? And finally, why is there something rather than nothing?” One of the few prominent scientists today to have crossed the chasm between science and popular culture, Krauss describes the staggeringly beautiful experimental observations and mind-bending new theories that demonstrate not only can something arise from nothing, something will always arise from nothing. With a new preface about the significance of the discovery of the Higgs particle, A Universe from Nothing uses Krauss’s characteristic wry humor and wonderfully clear explanations to take us back to the beginning of the beginning, presenting the most recent evidence for how our universe evolved—and the implications for how it’s going to end. Provocative, challenging, and delightfully readable, this is a game-changing look at the most basic underpinning of existence and a powerful antidote to outmoded philosophical, religious, and scientific thinking” ( Daniel M. Cable, Alive at Work: The Neuroscience of Helping Your People Love What They Do (Harvard Business Review Press, 2018): “In this bold, enlightening book, social psychologist and professor Daniel M. Cable takes leaders into the minds of workers and reveals the surprising secret to restoring their zest for work. Disengagement isn’t a motivational problem, it’s a biological one. Humans aren’t built for routine and repetition. We’re designed to crave exploration, experimentation, and learning–in fact, there’s a part of our brains, which scientists have coined “the seeking system,” that rewards us for taking part in these activities. But the way organizations are run prevents many of us from following our innate impulses. As a result, we shut down. Things need to change. More than ever before, employee creativity and engagement are needed to win. Fortunately, it won’t take an extensive overhaul of your organizational culture to get started. With small nudges, you can personally help people reach their fullest potential. Alive at Work reveals:

Daniel M. Cable, Alive at Work: The Neuroscience of Helping Your People Love What They Do (Harvard Business Review Press, 2018): “In this bold, enlightening book, social psychologist and professor Daniel M. Cable takes leaders into the minds of workers and reveals the surprising secret to restoring their zest for work. Disengagement isn’t a motivational problem, it’s a biological one. Humans aren’t built for routine and repetition. We’re designed to crave exploration, experimentation, and learning–in fact, there’s a part of our brains, which scientists have coined “the seeking system,” that rewards us for taking part in these activities. But the way organizations are run prevents many of us from following our innate impulses. As a result, we shut down. Things need to change. More than ever before, employee creativity and engagement are needed to win. Fortunately, it won’t take an extensive overhaul of your organizational culture to get started. With small nudges, you can personally help people reach their fullest potential. Alive at Work reveals: Newell G. Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, & Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism, 2nd ed. (Greg Kofford Books, 2018): “Originally published shortly after the LDS Church lifted its priesthood and temple restriction on black Latter-day Saints, Newell G. Bringhurst’s landmark work remains ever-relevant as both the first comprehensive study on race within the Mormon religion and the basis by which contemporary discussions on race and Mormonism have since been framed. Approaching the topic from a social history perspective, with a keen understanding of antebellum and post-bellum religious shifts, Saints, Slaves, and Blacks examines both early Mormonism in the context of early American attitudes towards slavery and race, and the inherited racial traditions it maintained for over a century. While Mormons may have drawn from a distinct theology to support and defend racial views, their attitudes towards blacks were deeply-embedded in the national contestation over slavery and anticipation of the last days. This second edition of Saints, Slaves, and Blacks offers an updated edit, as well as an additional foreword and postscripts by Edward J. Blum, W. Paul Reeve, and Darron T. Smith. Bringhurst further adds a new preface and appendix detailing his experience publishing Saints, Slaves, and Blacks at a time when many Mormons felt the rescinded ban was best left ignored, and reflecting on the wealth of research done on this topic since its publication” (

Newell G. Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, & Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism, 2nd ed. (Greg Kofford Books, 2018): “Originally published shortly after the LDS Church lifted its priesthood and temple restriction on black Latter-day Saints, Newell G. Bringhurst’s landmark work remains ever-relevant as both the first comprehensive study on race within the Mormon religion and the basis by which contemporary discussions on race and Mormonism have since been framed. Approaching the topic from a social history perspective, with a keen understanding of antebellum and post-bellum religious shifts, Saints, Slaves, and Blacks examines both early Mormonism in the context of early American attitudes towards slavery and race, and the inherited racial traditions it maintained for over a century. While Mormons may have drawn from a distinct theology to support and defend racial views, their attitudes towards blacks were deeply-embedded in the national contestation over slavery and anticipation of the last days. This second edition of Saints, Slaves, and Blacks offers an updated edit, as well as an additional foreword and postscripts by Edward J. Blum, W. Paul Reeve, and Darron T. Smith. Bringhurst further adds a new preface and appendix detailing his experience publishing Saints, Slaves, and Blacks at a time when many Mormons felt the rescinded ban was best left ignored, and reflecting on the wealth of research done on this topic since its publication” ( Benjamin Powell, Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy (Cambridge University Press, 2014): “This book provides a comprehensive defense of third-world sweatshops. It explains how these sweatshops provide the best available opportunity to workers and how they play an important role in the process of development that eventually leads to better wages and working conditions. Using economic theory, the author argues that much of what the anti-sweatshop movement has agitated for would actually harm the very workers they intend to help by creating less desirable alternatives and undermining the process of development. Nowhere does this book put ‘profits’ or ‘economic efficiency’ above people. Improving the welfare of poorer citizens of third world countries is the goal, and the book explores which methods best achieve that goal. Out of Poverty will help readers understand how activists and policy makers can help third world workers” (

Benjamin Powell, Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy (Cambridge University Press, 2014): “This book provides a comprehensive defense of third-world sweatshops. It explains how these sweatshops provide the best available opportunity to workers and how they play an important role in the process of development that eventually leads to better wages and working conditions. Using economic theory, the author argues that much of what the anti-sweatshop movement has agitated for would actually harm the very workers they intend to help by creating less desirable alternatives and undermining the process of development. Nowhere does this book put ‘profits’ or ‘economic efficiency’ above people. Improving the welfare of poorer citizens of third world countries is the goal, and the book explores which methods best achieve that goal. Out of Poverty will help readers understand how activists and policy makers can help third world workers” (