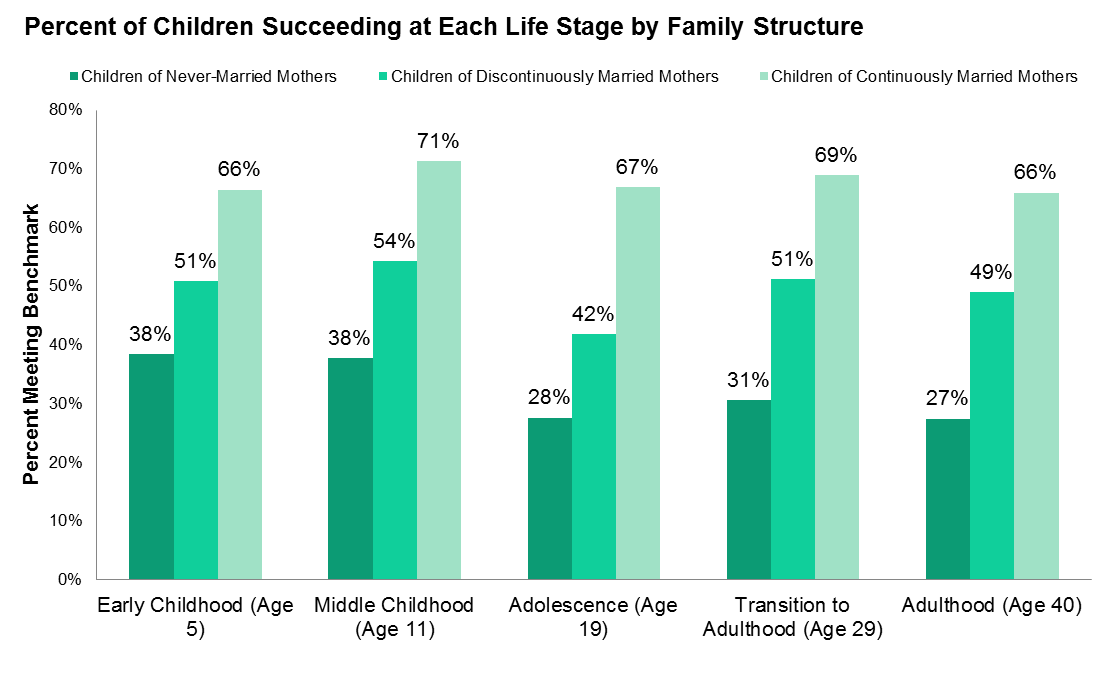

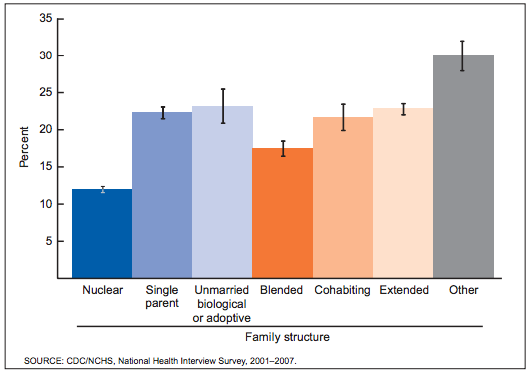

The above graph comes from yet another post at the Brookings Institution, which finds that marriage leads to better outcomes for children. However, this study breaks it down into two main reasons:

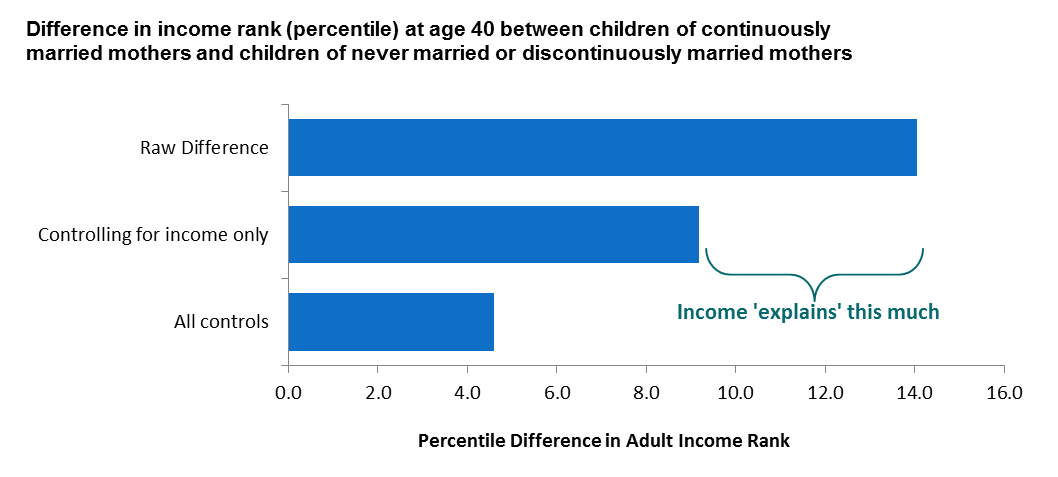

- More money: the income effect

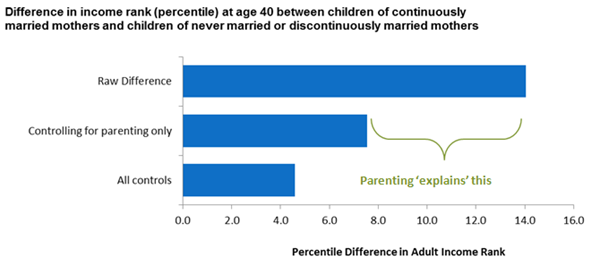

- More engaged parenting: the parenting effect

However, the authors come to an interesting conclusion:

If the benefits of marriage for children can be explained by other observable characteristics of the family, and especially money or parenting behavior, then policy may be more successful if focused on those pathways. It would be convenient to find the magic bullet – the one family input that really matters – but of course the truth is messier. Children’s life chances will be influenced by a complicated, shifting mesh of family characteristics (and many other factors outside the family).

Marriage is a powerful means by which incomes can be raised and parenting can be improved. But marriage itself seems immune to the ministrations of policymakers. In which case, policies to increase the incomes of unmarried parents, especially single parents, and to help parents to improve their parenting skills, should be where policy energy is now expended.

Yet, W. Bradford Wilcox of the University of Virginia and director of the National Marriage Project points out that

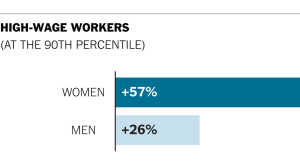

marriage itself fosters higher income and better parenting among today’s parents. For instance, men who get and stay married work longer hours and make more money than their unmarried peers. And fathers and mothers who are in an intact marriage tend to engage in more involved, affectionate, and consistent parenting than their peers in single- or step-families.

The bigger point is this: you cannot easily strip marriage of its constituent parts, such as more money and a supportive parenting environment, give those parts to parents apart from marriage, and expect that children will do as well, apart from marriage.