Pew Research Center has a new study out on American’s religious beliefs. Their previous research on the rise of the “nones” (i.e., the unchurched or religiously unaffiliated) received a lot of press with many claiming that religious belief was on the decline. Sociologist Rodney Stark has been calling out the misleading nature of these numbers, pointing out that a lack of religious affiliation does not say much about the person’s beliefs. His criticisms are based on his detailed, large-scale survey of Americans’ beliefs and practices as well as his analysis of cross-country data. And now, Pew’s recent research seems to indicate that Stark had a point:

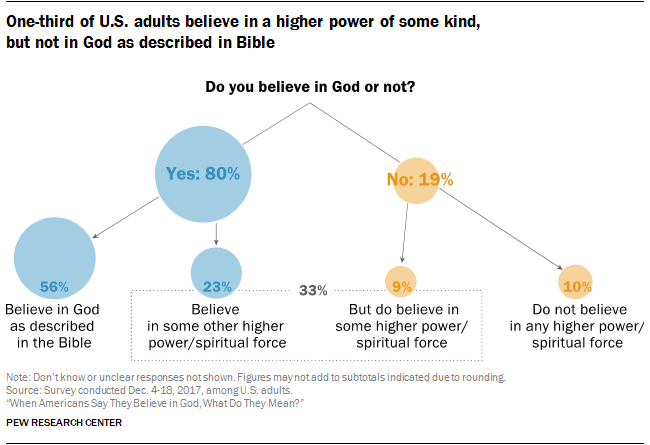

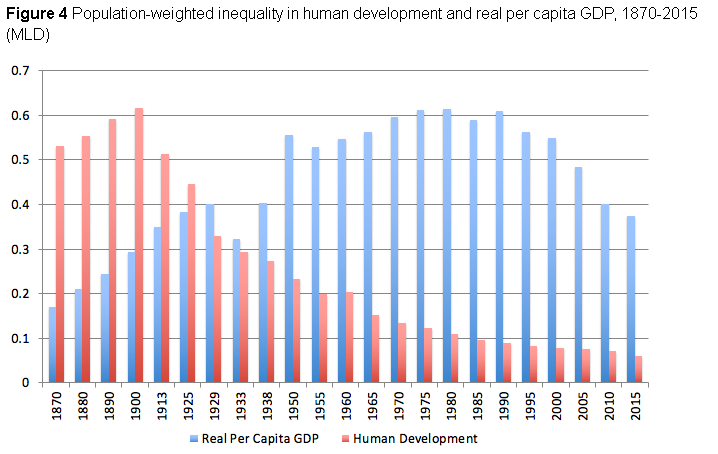

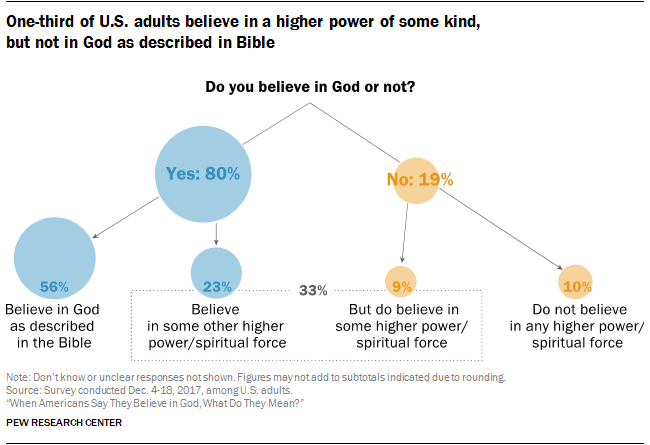

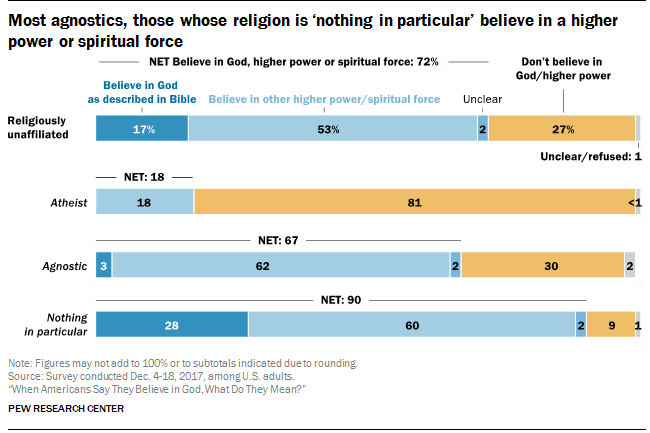

A new Pew Research Center survey of more than 4,700 U.S. adults finds that one-third of Americans say they do not believe in the God of the Bible, but that they do believe there is some other higher power or spiritual force in the universe. A slim majority of Americans (56%) say they believe in God “as described in the Bible.” And one-in-ten do not believe in any higher power or spiritual force.

…The survey questions that mention the Bible do not specify any particular verses or translations, leaving that up to each respondent’s understanding. But it is clear from questions elsewhere in the survey that Americans who say they believe in God “as described in the Bible” generally envision an all-powerful, all-knowing, loving deity who determines most or all of what happens in their lives. By contrast, people who say they believe in a “higher power or spiritual force” – but not in God as described in the Bible – are much less likely to believe in a deity who is omnipotent, omniscient, benevolent and active in human affairs.

And what of the so-called “nones”?:

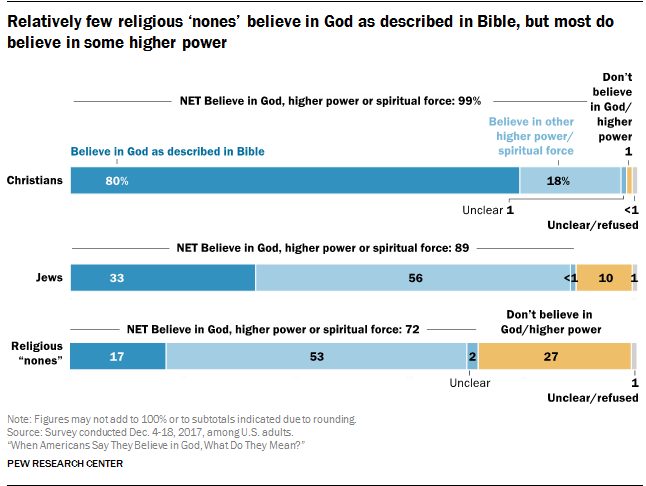

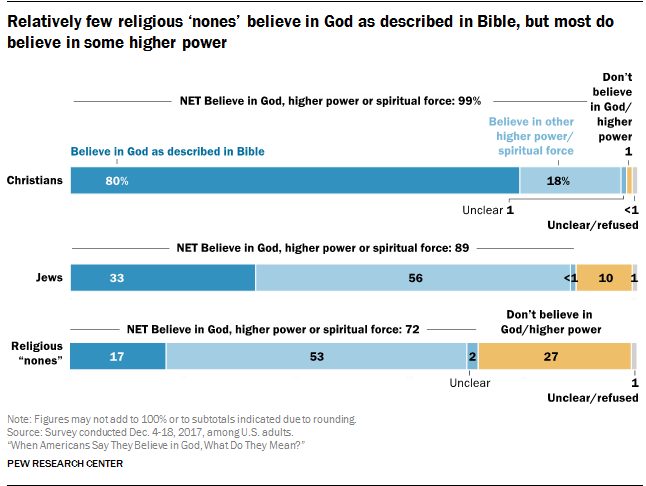

Compared with Christians, Jews and people with no religious affiliation are much more likely to say they do not believe in God or a higher power of any kind. Still, big majorities in both groups do believe in a deity (89% among Jews, 72% among religious “nones”), including 56% of Jews and 53% of the religiously unaffiliated who say they do not believe in the God of the Bible but do believe in some other higher power of spiritual force in the universe. (The survey did not include enough interviews with Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus or respondents from other minority religious groups in the United States to permit separate analysis of their beliefs.)

As Stark writes,

The world is more religious than it has ever been. Around the globe, four out of every five people claim to belong to an organized faith, and many of the rest say they attend worship services. In Latin American, Pentecostal Protestant churches have converted tens of millions, and Catholics are going to Mass in unprecedented numbers. There are more churchgoing Christians in Sub-Saharan African than anywhere else on earth, and China may soon become home of the most Christians. Meanwhile, although not growing as rapidly as Christianity, Islam enjoys far higher levels of member commitment than it has for many centuries, and the same is true for Hinduism. In fact, of all the great world religions, only Buddhism may not be growing…[D]espite [the] confident proclamations about the decline of religion, Pew’s findings were certainly misleading and probably wrong. Consider only one fact: the overwhelming majority of Americans who say they have no religious affiliation pray and believe in angels! How irreligious is that?[ref]The Triumph of Faith, pg. 1-2.[/ref]

Furthermore,

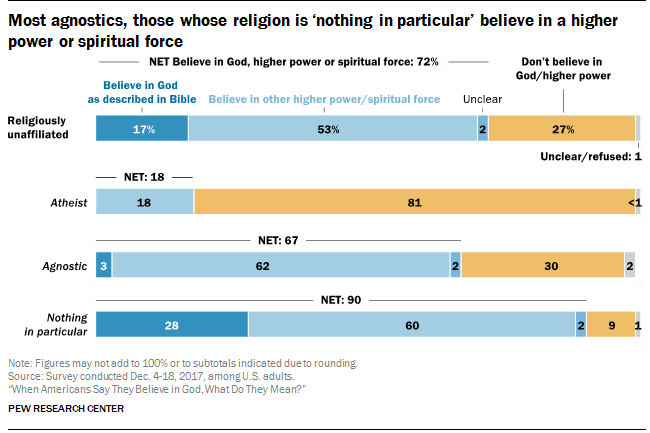

The [Pew] findings would seem to be clear: the number of Americans who say their religious affiliation is “none” has increased from about 8 percent in 1990 to about 22 percent in 2014. But what this means is not so obvious, for, during this same period, church attendance did not decline and the number of atheists did not increase. Indeed, the percentage of atheists in America has stayed stead at about 4 percent since a question about belief in God was first asked in 1944. In addition, except for atheists, most of the other “nones” are religious in the sense that they pray (some pray very often) and believe in angels, in heaven, and even in ghosts. Some are also rather deeply involved in “New Age” mysticisms.

So who are these “nones,” and why is their number increasing–if it is? Back in 1990 most Americans who seldom or never attended church still claimed a religious affiliation when asked to do so. Today, when asked their religious preference, instead of saying Methodist or Catholic, now a larger proportion of nonattenders say “none,” by which most seem to mean “no actual membership.” The entire change has take place within the nonattending group, and the nonattending group has not grown.

In other words, this change marks a decrease only in nominal affiliation, not an increase in irreligion. So whatever else it may reflect, the change does not support claims for increased secularization, let alone a decrease in the number of Christians. It may not even reflect an increase in those who say they are “nones.” The reason has to do with response rates and the accuracy of surveys.[ref]Ibid., 190.[/ref]

Assessing the size and identifying the sources of gains from trade is a long-standing challenge for economists. Theoretical and quantitative studies have mostly focused on static economies where changes in international market integration have only one-off effects on the levels of income and consumption but do not affect the long-run dynamics of these key economic variables (Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare, 2014). Since innovation and technological change are key drivers of income growth in the long-run (Aghion and Howitt, 2009, Akcigit et al. 2017), in a recent paper (Impullitti and Licandro 2018) we explore the sources and assess the size of the gains from trade in an economy where growth spurs from technological progress.

Assessing the size and identifying the sources of gains from trade is a long-standing challenge for economists. Theoretical and quantitative studies have mostly focused on static economies where changes in international market integration have only one-off effects on the levels of income and consumption but do not affect the long-run dynamics of these key economic variables (Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare, 2014). Since innovation and technological change are key drivers of income growth in the long-run (Aghion and Howitt, 2009, Akcigit et al. 2017), in a recent paper (Impullitti and Licandro 2018) we explore the sources and assess the size of the gains from trade in an economy where growth spurs from technological progress.

Total wealth in the new approach is calculated by summing up estimates of each component of wealth: produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and net foreign assets. This represents a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by (1) assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth and then (2) calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption…In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual.

Total wealth in the new approach is calculated by summing up estimates of each component of wealth: produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and net foreign assets. This represents a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by (1) assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth and then (2) calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption…In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual.