As I was reading this fairly recent article on Denmark’s labor markets, the following jumped out at me:

The strong correlation between labor freedom and low unemployment rates seems to explain why Denmark has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the EU.

…A well-functioning and efficient labor market is, no doubt, one of the ingredients which account for Denmark’s economic prosperity. It is certainly responsible for the low unemployment rates the country has enjoyed over the last decades. The Danish experience should open the eyes of those European governments that refuse to undertake reforms which liberalize their labor markets. The evidence is clear: labor flexibility results in lower unemployment. Will the Danish example be followed by those countries badly hit by the plague of unemployment?

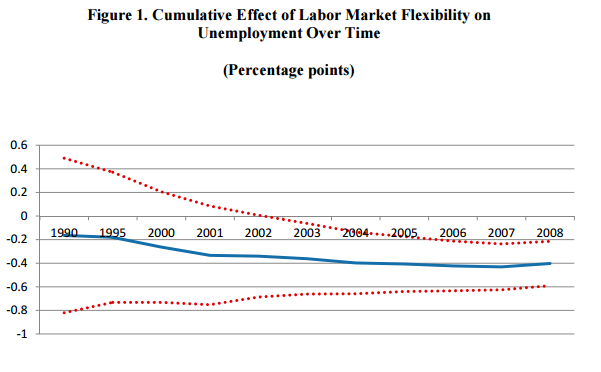

The papers the author cites are worth highlighting. The first is a 2012 IMF paper analyzing 97 countries from 1985 to 2008. The researchers report,

Our findings indicate that, after controlling for other macroeconomic and demographic variables, increases in the flexibility of labor market regulations and institutions have a statistically significant negative impact both on the level and the change of unemployment outcomes (i.e., total, youth, and long-term unemployment). Among the different labor market flexibility indicators analyzed, hiring and firing regulations and hiring costs are found to have the strongest effect.

Overall the results of the paper suggest that policies that enhance labor market flexibility should reduce unemployment. At the same time, this raises the issue of the design and possible sequence of such reforms, and the adoption of policies aimed also to improve the quality of employment and to minimize possible negative short-term effects, not investigated in this paper, on inequality and job destruction. While data available for our large set of countries lack the necessary level of details to answer this question, micro- and macro-studies on OECD countries over the decade showed that it is important to protect workers, rather than jobs, by coupling of unemployment benefits with pressure on unemployed to take jobs and measures to help them (Blanchard, 2006). Moreover, employment protection should be designed in such a way to internalize social costs and not inhibit job creation and labor reallocation. Artificial restrictions on individual employment contracts should also be avoided (pg. 12).

The next piece is a 2016 working paper that explores labor markets in Italy from 2001-2013. It explains,

Why have unemployment dynamics been so different in European countries? One of the most often cited explanation is the difference in labor market institutions that prevents wages from adjusting downward. If wages cannot decline, negative aggregate demand shocks (such as the Great Recession) result in unemployment growth. On the other hand, if wages can fall, labor markets reach a new equilibrium with unemployment rates returning to normal levels. Downward adjustment of wages in response to macroeconomic shocks is especially important in the euro area where labor markets cannot accommodate shocks through exchange rate depreciation or through internal labor mobility (migration among EU countries is much more limited than, for example, labor mobility across US states).

…We find that the wage differential between formal/regulated and informal/unregulated sectors has increased after 2008. Moreover, while wages in the informal sector decreased by about 20 percent in 2008-13, wages in the formal sector virtually did not fall. This is consistent with the view of a substantial downward stickiness of wages in the regulated labor market. Importantly, before the recession, wages in the formal and informal sectors moved in parallel — confirming the validity of the parallel trends assumption required for a difference-in-differences estimation and showing that both regulated and unregulated labor markets have a similar degree of upward flexibility of wages.

We also analyze the impact of the crisis on formal and informal employment. We find that formal employment decreases substantially while informal employment does not change. Since the aggregate demand shock affects both labor markets, this finding implies that upon losing a job in the formal sector at least some workers move to the informal sector. We calibrate a simple model describing such spillovers between formal and informal labor markets. Using the existing estimates for demand and supply elasticities for the Italian labor market, we estimate the degree of integration of formal and informal sector (i.e. the share of workers who move from the formal to the informal labor market after the crisis). Our model also allows to carry out a counterfactual analysis of the formal sector’s response to crisis in a scenario where formal wages were fully flexible. We find that in this case the crisis would have resulted in a much smaller decline in formal employment between 2008 and 2013 (1.5-4.5 percent rather than the actual 16 percent) (pg. 3-4).

Important information for policy makers.

Adam was placed in the Garden of Eden “to dress it and to keep it” (Genesis 2:15). Labor is not only the destiny of man; it is endowed with divine dignity. However, after he ate of the tree of knowledge he was condemned to toil, not only to labor “In toil shall thou eat … all the days of thy life” (Genesis 3:17). Labor is a blessing, toil is the misery of man. The Sabbath as a day of abstaining from work is not a depreciation but an affirmation of labor, a divine exaltation of its dignity. Thou shalt abstain from labor on the seventh day is a sequel to the command: Six days shalt thou labor, and do all thy work [Ex. 20:9]…The duty to work for six days is just as much a part of God’s covenant with man as the duty to abstain from work on the seventh day.[ref]

Adam was placed in the Garden of Eden “to dress it and to keep it” (Genesis 2:15). Labor is not only the destiny of man; it is endowed with divine dignity. However, after he ate of the tree of knowledge he was condemned to toil, not only to labor “In toil shall thou eat … all the days of thy life” (Genesis 3:17). Labor is a blessing, toil is the misery of man. The Sabbath as a day of abstaining from work is not a depreciation but an affirmation of labor, a divine exaltation of its dignity. Thou shalt abstain from labor on the seventh day is a sequel to the command: Six days shalt thou labor, and do all thy work [Ex. 20:9]…The duty to work for six days is just as much a part of God’s covenant with man as the duty to abstain from work on the seventh day.[ref]