I’ve mentioned the World Bank’s measurement of intangible assets before. Its recent report–The Changing Wealth of Nations 2018: Building a Sustainable Future–updates this measurement:

Total wealth in the new approach is calculated by summing up estimates of each component of wealth: produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and net foreign assets. This represents a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by (1) assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth and then (2) calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption…In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual.

Total wealth in the new approach is calculated by summing up estimates of each component of wealth: produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and net foreign assets. This represents a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by (1) assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth and then (2) calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption…In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual.

The unexplained residual, called “intangible capital,” was largely attributed to human capital…as well as to missing or mismeasured assets and possible effects of social capital. But the unexplained residual accounted for 50–85 percent of the total wealth indicator, making it a weak indicator for policy. This approach was taken because of the lack of data for directly measuring human capital. We now have a method and data for estimating human capital directly and will measure total wealth as the sum of each asset category. The advantage of the earlier approach was that the residual included human capital, unmeasured assets, and the influence of institutions and governance on wealth. The disadvantage was that the various components of the residual could not be disentangled and it was calculated assuming the same return on assets in all countries.

Human capital in the past was not measured explicitly but included as part of the “residual,” accounting for 50–85 percent of total wealth in past estimates. We apply the well-known Jorgenson Fraumeni lifetime earnings approach to measuring human capital globally. We use a unique database developed by the World Bank, the International Income Distribution Database, which contains more than

1,500 household surveys (pgs. 38-39).

This report

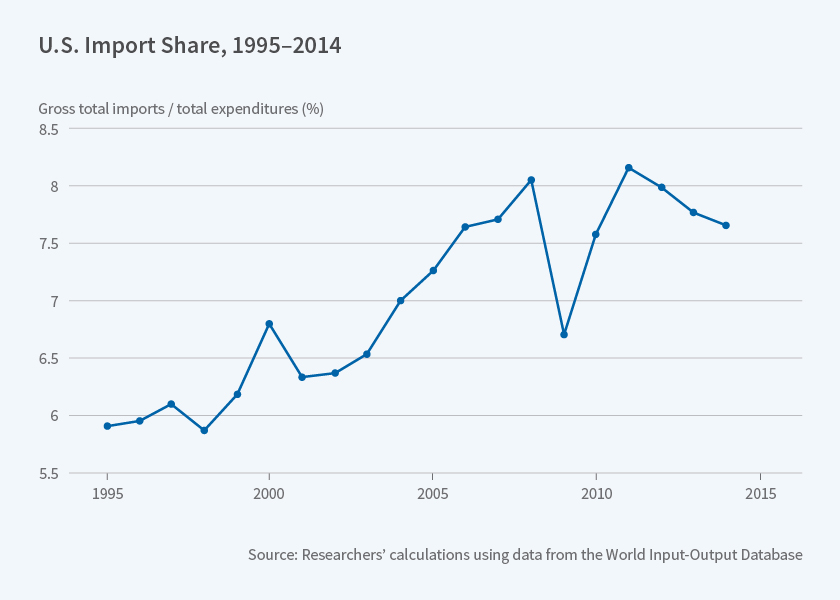

shows for the first time that much of intangible wealth is actually human capital, estimated as the net present value of the population’s future labor earnings. Human capital turns out to be the most important component of wealth, even though its share in total wealth decreased from 69 percent in 1995 to 64 percent in 2014 (table 2.2). After 2000, this decline in the share of human capital wealth was entirely due to upper-middle and high-income OECD countries, which together account for more than 80 percent of global wealth as well as most human capital wealth. The factors that led to this decline include the aging of the labor force (which reduces the remaining years of earnings) in many high-income OECD countries, as well as in China, which dominates the upper-middle-income country group, and declining wage shares in GDP, particularly in many high-income OECD countries (ILO 2015). By contrast, in low- and lower-middle-income countries, which account for the majority of the world’s population, the share of human capital in total wealth is rising (pgs. 46-47).

The new report calculates total wealth as follows:

Total wealth = Natural capital + Produced capital + Human capital + Net foreign assets

“This represents a significant departure from past estimates,” the report explains,

in which total wealth was estimated by assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth, and then calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption (“top-down approach”). In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual. The unexplained residual, called “intangible capital,” was largely attributed to human capital as well as to missing or mismeasured assets. Now with a direct measurement of human capital,[ref]See Ch. 6 for an explanation of the methodology for measuring human capital.[/ref] total wealth can be estimated as the sum of all categories of assets (pg. 212).

In turns out that the U.S. has $983,280 total wealth per capita with human capital making up $766,470 (see pg. 232). Other findings include:

- The report found that global wealth grew 66 percent (from $690 trillion to $1,143 trillion in constant 2014 U.S. dollars at market prices).

- The top 20 countries with the fastest growing wealth per capita were dominated by developing countries—including two of the biggest—China and India, which were both classified by the World Bank as low income countries in 1995 and are now ranked as middle-income.

- Countries with large gains in per capita wealth also included smaller countries like Chile, Peru, Vietnam, as well as countries rapidly recovering from civil disturbances like Bosnia-Herzegovina, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Sri Lanka as well as some of the resource rich countries in the former USSR, like Azerbaijan.

- Per capita wealth declined or was stagnant in more than two dozen countries in various income brackets. These include several large low-income countries, some carbon-rich countries in the Middle East, and high-income OECD countries affected by the 2009 financial crisis. Declining per capita wealth implies that assets critical for generating future income may be depleted, and the rents generated from natural assets depletion are not invested properly, a fact often not reflected in national GDP growth figures.

- Human capital is the largest component of global wealth, accounting for two thirds of total wealth globally. This points to the need to invest in people for wealth creation and future income generation.

- While natural capital accounts for 9 percent of wealth globally, it makes up nearly half (47 percent) of the wealth in low income countries. More efficient, long-term management of natural resources is key to sustainable development while these countries build their infrastructure and human capital.

Immigration policy is controversial topic in 2018. In response to refugee crises and legal situations that can break up families, the LDS Church announced its “I Was a Stranger” relief effort and released a statement encouraging solutions that strengthens families, keeps them together, and extends compassion to those seeking a better life. This article seeks to shed light on a correct understanding of immigration and its effects. Walker Wright gives a brief scriptural overview of migration, explores the public’s attitudes toward immigration, and reviews the empirical economic literature, which shows that (1) fears about immigration are often overblown or fueled by misinformation and (2) liberalizing immigration restrictions would have positive economic effects.

Immigration policy is controversial topic in 2018. In response to refugee crises and legal situations that can break up families, the LDS Church announced its “I Was a Stranger” relief effort and released a statement encouraging solutions that strengthens families, keeps them together, and extends compassion to those seeking a better life. This article seeks to shed light on a correct understanding of immigration and its effects. Walker Wright gives a brief scriptural overview of migration, explores the public’s attitudes toward immigration, and reviews the empirical economic literature, which shows that (1) fears about immigration are often overblown or fueled by misinformation and (2) liberalizing immigration restrictions would have positive economic effects.

Total wealth in the new approach is calculated by summing up estimates of each component of wealth: produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and net foreign assets. This represents a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by (1) assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth and then (2) calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption…In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual.

Total wealth in the new approach is calculated by summing up estimates of each component of wealth: produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and net foreign assets. This represents a significant departure from past estimates, in which total wealth was estimated by (1) assuming that consumption is the return on total wealth and then (2) calculating back to total wealth from current sustainable consumption…In previous estimates, produced capital, natural capital, and net foreign assets were calculated directly, then subtracted from total wealth to obtain a residual.

Because managers and workers apply different skills, the best workers may not be the best candidates for managers. When this is the case, do firms promote someone who excels in her current position, or someone who is likely to excel as a manager? If firms promote based on current performance, then firms may end up with worse managers. Yet if firms promote based on traits that predict managerial potential, then firms may pass over higher performing workers, weakening the power of promotions to encourage workers to perform well in their current roles. Such promotion policies could also lead to perceptions of favoritism, unfairness, or that succeeding in one’s job goes unrewarded.

Because managers and workers apply different skills, the best workers may not be the best candidates for managers. When this is the case, do firms promote someone who excels in her current position, or someone who is likely to excel as a manager? If firms promote based on current performance, then firms may end up with worse managers. Yet if firms promote based on traits that predict managerial potential, then firms may pass over higher performing workers, weakening the power of promotions to encourage workers to perform well in their current roles. Such promotion policies could also lead to perceptions of favoritism, unfairness, or that succeeding in one’s job goes unrewarded. There is surprisingly little direct quantitative evidence on how the U.S. economy would react if the door were shut on trade. To find a precedent, the researchers point out that one could go back to the Embargo Act of 1807, when the United States banned trade with Great Britain and France in retaliation for their repeated violations of U.S. neutrality. GDP declined sharply, but the agrarian world during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson bears little resemblance to today’s high-tech, service-oriented economy.

There is surprisingly little direct quantitative evidence on how the U.S. economy would react if the door were shut on trade. To find a precedent, the researchers point out that one could go back to the Embargo Act of 1807, when the United States banned trade with Great Britain and France in retaliation for their repeated violations of U.S. neutrality. GDP declined sharply, but the agrarian world during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson bears little resemblance to today’s high-tech, service-oriented economy.