In today’s political climate, I often hear some pretty ridiculous things about religion. From liberal atheists to Republican Presidential candidates (here’s looking at you Trump and Cruz), the ignorance abounds. The video below is an excellent reminder as to why religious literacy is important. Check it out.

Month: April 2016

Guaranteed Basic Income: A 10+ Year Experiment

The organization GiveDirectly is about to embark on a potentially paradigm-shifting social experiment:

to try to permanently end extreme poverty across dozens of villages and thousands of people in Kenya by guaranteeing them an ongoing income high enough to meet their basic needs—a universal basic income, or basic income guarantee. We’ve spent much of the past decade delivering cash transfers to the extremely poor through GiveDirectly, but have never structured the transfers exactly this way: universal, long-term, and sufficient to meetbasic needs. And that’s the point—nobody has and we think now is the time to try.

The reasons for this are evidence-based:

Across many contexts and continents, experimental tests show that the poor don’t stop trying when they are given money,[ref]There is evidence that government programs and benefits can discourage work (at least in an already rich country like the U.S.), including unemployment benefits, Social Security Disability Insurance and VA’s Disability Compensation, Obamacare, Medicaid, the Negative Income Tax, and other forms of welfare. Charles Murray argued decades ago that the welfare state creates perverse incentives. However, not all forms of welfare are created equal, which is the point of the debate.[/ref] and they don’t get drunk. Instead, they make productive use of the funds, feeding their families, sending their children to school, and investing in businesses and their own futures. Even a short-term infusion of capital has been shown to significantly improve long-term living standards, improve psychological well-being, and even add one year of life.

On the other hand, well-intentioned social programs have often fallen short. A recent World Bank study concludes that “skills training and microfinance have shown little impact on poverty or stability, especially relative to program cost.” Moreover, this paternalistic approach is often for naught: Jesse Cunha, for example, finds no differences in health and nutritional outcomes between providing basic foods and providing an equally sized cash program. Most importantly, though, the poor prefer the freedom, dignity, and flexibility of cash transfers—more than 80 percent of the poor in a study in Bihar, India, were willing to sell their food vouchers for cash, many at a 25 to 75 percent discount.

As the authors note, the “idea of a basic income guarantee is being debated around the globe, with pilots being considered by Finland’s center-right government and Canada’s liberal party, and support from across the political landscape, including libertarians from the Cato Institute[ref]Slight quibble: the essay is for Cato Unbound, but Matt Zwolinski isn’t with the Cato Institute. Nonetheless, Zwolinski has praised GiveDirectly.[/ref] and liberals from the Brookings Institution.”

“But fundamentally,” the authors point out,

the question should be an empirical one: What are the impacts of a universal basic income? And how do they compare with other forms of assistance?

We’re planning to find out. To do so, we’re planning to provide at least 6,000 Kenyans with a basic income for 10 to 15 years. These recipients are some of the most vulnerable people in the world, living on the U.S. equivalent of less than a dollar. And we’re going to work with leading academic researchers, including Abhijit Banerjee of MIT, to rigorously test the impacts.

…To get started, we’re putting in $10 million of our own funds to match the first $10 million donated by others. At worst that money will shift the life trajectories of thousands of low-income households. At best, it will change how the world thinks about ending poverty.

This is really exciting stuff. See more on it here.

Brigham Young: A Lecture by John G. Turner

This is part of the DR Book Collection.

In her review of Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet by GMU historian John G. Turner, Julie Smith writes,

In her review of Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet by GMU historian John G. Turner, Julie Smith writes,

I suspect that John G. Turner’s Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet will be the definitive biography of Brigham Young for the next few decades. Overall, this is a good thing.

But it may also be a troubling thing, at least for some people. I wholeheartedly recommended the recent Joseph Smith, David O. McKay, and Spencer W. Kimball biographies to all members of the Church. Sure, they are a little less sanitized than we are used to, but the picture in each one of those works is of a prophet of God who had some flaws, with far more emphasis on the “prophet” part than on the “flawed” part.

This book? Not so much. I have serious reservations about recommending it to the average church member; if you need your prophet to be larger than life, or even just better than the average bear, this book is not for you. I think there is a substantial risk that people raised on hagiographic, presentist images of prophets would have their testimonies rocked, if not shattered, by this book.

…So, here’s the Readers’ Digest version of my review: this book is a real treat, but it might completely destroy your testimony if you can’t handle a fallible, bawdy, often mistaken, sometimes mean, and generally weird prophet.

The book truly is incredible, doing for Brigham Young what Richard Bushman did for Joseph Smith. However, I agree with Julie that “the main weakness of this book” is the fact that “you are not left with any reason as to why people would have made the enormous sacrifices that were part of believing that Brigham Young was a prophet.” To fill in these gaps, here are the reported words of Turner from my friend Carl Cranney on Young’s appeal:

Why did people follow Brigham? He admitted to me and the others in the study group a few weeks ago that he felt he could have handled this question better. He pointed out three things, specifically, that Brigham had done before he became the de facto church president, and later actual church president, that garnered him a lot of good will from the members. First, many of the church members were from the British Isles, and Brigham had led the British mission. So many members of the church had fond memories of him as the leader of the missionaries that brought them into the church. Second, he finished the Nauvoo temple and endowed thousands of Mormons before they abandoned the city. The sheer amount of man-hours this took would have staggered anybody but the firmest believer. Brigham Young was a believer, and it showed to the people that he worked tirelessly for in the temple. Third, he was the “American Moses” who dragged a despondent group of church members from their Nauvoo the Beautiful to the middle of nowheresville, Mexico, to create a civilization literally out nothing in a sparsely-populated desert wilderness. He worked hard to preserve the church and to get its members to safety. So, after doing these three things he had garnered a lot of support and a lot of good will from the members.

Despite this oversight, the book is fantastic and the go-to biography of Brigham Young.

Check out John Turner’s lecture on the bio at Benchmark Books below:

The Plight of the Poor in the U.S.

In the comments on my last post, Robert C made an important point based on his own experience that “the poor in the U.S. experience a high degree of social, emotional, and psychological stress in comparison to the lack of such stress among the relatively rich in other countries.” My interest in economics and data is largely about providing proper context and analysis, but sometimes it can make me look like a cold-blooded bastard.

Robert is right though. The working class in America does face major problems. The experiences of those growing up in working-class neighborhoods are often traumatic and these experiences have negative effects on economic outcomes (let alone well-being). David Lapp, a research fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, had a powerful reply to a couple recent articles blasting the American white working class. As Lapp tells it,

No true calamity or awful disaster has befallen the white working class?

Try telling that to [the boy] whose own mother abused him and whose parents left him. Try telling that to the girl molested by her mother’s boyfriend, or the little girl whose mom and boyfriend passed out in the McDonald’s parking lot because of a heroin overdose, or the 10-year-old boy who walked into his parents’ bedroom to find his dad having sex with a stranger. (Those are just some of the typical stories we heard in our interviews with members of the working class in Ohio.) As one young man told me, “Besides killing a small child I would say that divorce is the second-worst thing that can ever happen. Because divorce is the symbol of violently breaking apart. Like in my case, my dad and my mom separating, it tore the family apart, literally. It was the symbol of breaking apart and shards went everywhere.”

I understand the point that Williamson and French are trying to make: when we speak of divorce and abuse and heroin and father absence, we are not talking about the factory that left, but acts perpetrated by adults with moral responsibilities. But that is no solace to the young victims—yes, we must speak of victims—of those traumatic events.

Because the divorce culture is a true calamity for generations of young people growing up in the aftermath. Nor should we imagine that just because a cause is cultural or familial, and not economic, that it involves no victims. As Rod Dreher writes in a response to Williamson’s post, “Children are not empty receptacles into which we can insert knowledge. If they live in homes filled with noise, chaos, violence, and contempt, it doesn’t matter what race they are, they are going to be very lucky to make it.”

Families are in trouble, but people aren’t making bad decisions in isolation. The family is in trouble because marriage is a social institution, and many young people have seen their own parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents divorce (sometimes two, three, and four times). Whatever the reasons for divorce that the pioneers of the divorce revolution had, the young people walking into marriage today—or looking bewilderingly at it from the outside—are left feeling broken. That raises serious questions.

…We can always point to some people who grew up in troubled families and nevertheless succeed. We admire their courage and perseverance. Still, isn’t it self-evident that a child who suffers his parents’ divorce, or the absence of his father, or parental abuse, is much less likely to form good and lasting relationships as an adult? More likely to despair and resort to Oxycontin and heroin? And shouldn’t that fact matter for how we think and talk about the problems that confront the poor and working class, many of whom suffer these traumas?

Lapp recognizes that narratives about the poor often fall into two extreme categories and that he could easily adopt one of these extremes in telling of the story of those he’s interviewed. One extreme highlights external factors and lack of resources (typically the political left), but this largely ignores the poor’s “own words about how things could have been different if they had made different choices.” The other extreme focuses “almost exclusively on these young adults’ own moral responsibilities, and downplay the cultural and economic forces and trauma clearly impinging on their lives” (typically the political right). “The true story,” Lapp says, “…is one that shows how cultural and economic forces and trauma intersect with people’s own free decisions.” To “scold the “downscale” people about their sins and “entitlement” and their communities “that deserve to die”” is to assume that “a person suffering from years of trauma and deprived of good models of family life could just snap out of it with a few good rebukes.” When we do this, we fail “to look squarely at not just “the problem,” but the person in front of us.”

Lapp recognizes that narratives about the poor often fall into two extreme categories and that he could easily adopt one of these extremes in telling of the story of those he’s interviewed. One extreme highlights external factors and lack of resources (typically the political left), but this largely ignores the poor’s “own words about how things could have been different if they had made different choices.” The other extreme focuses “almost exclusively on these young adults’ own moral responsibilities, and downplay the cultural and economic forces and trauma clearly impinging on their lives” (typically the political right). “The true story,” Lapp says, “…is one that shows how cultural and economic forces and trauma intersect with people’s own free decisions.” To “scold the “downscale” people about their sins and “entitlement” and their communities “that deserve to die”” is to assume that “a person suffering from years of trauma and deprived of good models of family life could just snap out of it with a few good rebukes.” When we do this, we fail “to look squarely at not just “the problem,” but the person in front of us.”

The complexities of poverty demonstrate the need for strong communities, families, churches, charities, and yes, even government programs. I still think economic growth does far more to lift the poor out of poverty than anything else. But when traumatic home life retards your emotional, psychological, educational, and economic development, this is not something that should be shamed. It’s something that should be dealt with through integration into a supportive social network.

And this–to borrow language from one of the recent critiques of the working class–requires us to “get off our asses” and help them out.

Remembering the Stranger

This is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

Perhaps the best irony about the GOP candidates’ rhetoric against the refugees is that it technically, according to the Bible, makes them Sodomites.

This was my friend Stephen Smoot‘s Facebook status a while back, referring to Ezekiel 16:49-50: “Behold this was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had pride, excess of food, and prosperous ease, but did not aid the poor and needy. They were haughty and did an abomination before me. So I removed them, when I saw it” (ESV). I was reminded of this with the launch of the Church’s new relief effort “I Was a Stranger.”

This is in the wake of the Church’s statement following Trump’s anti-Muslim remarks and the Utah governor’s acceptance of Syrian refugees. I’ve posted before about increasing immigration, seeing that it is one of the greatest anti-poverty tools available. The gospel of Jesus Christ should challenge our nationalistic and often racist attitudes. The 1972 address by (ironically)[ref]I say “ironically” because it was Lee who blocked the lifting of the priesthood ban back in 1969.[/ref] Harold B. Lee touches on this very theme:

One thing more I should like to state. We are having come into the Church now many people of various nationalities. We in the Church must remember that we have a history of persecution, discrimination against our civil rights, and our constitutional privileges being withheld from us. These who are members of the Church, regardless of their color, their national origin, are members of the church and kingdom of God. Some of them have told us that they are being shunned. There are snide remarks. We are withdrawing ourselves from them in some cases.

Now we must extend the hand of fellowship to men everywhere, and to all who are truly converted and who wish to join the Church and partake of the many rewarding opportunities to be found therein. To those who may not now have the priesthood, we pray that the blessings of Jesus Christ may be given to them to the full extent that it is possible for us to give them. Meanwhile, we ask the Church members to strive to emulate the example of our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, who gave us the new commandment that we should love one another. I wish we could remember that.

As do I.

The Position of the Church

This post is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

These days, there are many people who believe that the Church’s emphasis on family is something new and misguided, but I have long thought that—at a level even deeper than teaching or doctrine—the Church has long expressed a reality that family is primary and Church is secondary. What is this deeper level? Well, one way of looking that the Church is as modern day Sadducees: keepers of the temple. And what is the point of the temple? To seal families together.

In many ways that’s the most fundamental mission of the Church: to knit the entire human family together in one extended act of reconciliation. The Atonement is the center of the Church—both in practice and in belief—and the emphasis on family is like the ripples emanating out from that central act, echoes of reconciliation expanding and flowing throughout humanity, restoring what is broken and making us whole again not just as individuals, but as a collective.

Among the talks I read for this week, there was a line in Elder Victor L. Brown’s talk (The Aaronic Priesthood – A Sure Foundation) that made me think I could be on to something. He wrote:

The position of the Church is to aid the parents and the family.

It’s not definitive enough to hang your hat on all by itself, but it’s certainly something to think about. The Church exists to serve the family, not the other way around. And by “family” I mean both senses of the word. I mean my family and your family, our individual little clans here on Earth. And by “family” I also mean: all of us.

We teach our children to sing “I Am a Child of God.” And we take it seriously. In our words, in our songs, but most importantly in our actions.

—

Check out the other posts from the General Conference Odyssey this week and join our Facebook group to follow along!

- The Position of the Church by Nathaniel Givens

- Vaunting by G

- The Power of God Resting upon the Leaders of this Church by Daniel Ortner

- Remembering the Stranger by Walker Wright

- The Priesthood: Three Reasons to Honor It by Jan Tolman

Good Bosses and Workplace Happiness

Over at the Harvard Business Review, there’s a great post on the importance of human connection at work. It starts off by explaining that some research finds that employees prefer happiness at work to larger pay:

So what leads to employee happiness? A workplace characterized by humanity. An organizational culture characterized by forgiveness, kindness, trust, respect, and inspiration. Hundreds of studies conducted by pioneers of positive organizational psychology, including Jane Dutton and Kim Cameron at the University of Pennsylvania and Adam Grant at Wharton, demonstrate that a culture characterized by a positive work culture leads to improved employee loyalty, engagement, performance, creativity, and productivity. Given that about three-quarters of the U.S. workforce is disengaged at work — and the high cost of employee turnover — it’s about time organizations start paying attention to the data.

Research suggests that the most powerful way leaders can improve employee well-being is not through programs and initiatives but through day-to-day actions. For example, data from a large study run by Anna Nyberg at the Karolinska Institute shows that having a harsh boss is linked to heart problems in employees. On the other side of the coin, research demonstrates that leaders who are inspiring, empathic, and supportive have more loyal and engaged employees. So checking in with employees about their families once in a while may help more than offering a mindfulness class at lunchtime.

This is a powerful reminder that “organizations are first and foremost places of human interaction, not just transaction. Research shows that our greatest need after food and shelter is social connection — positive social relationships with others. If we create work environments characterized by these kinds of positive and supportive interactions, we create organizations that thrive.”

In other words, stop being a horrible boss.

Who Are “The Rich”?

In honor of former World Bank economist Branko Milanovic’s[ref]Nathaniel and I used some of Milanovic’s work in our SquareTwo article.[/ref] new book Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (out this month),[ref]You can find The Economist‘s review of the book here.[/ref] here is a NYT piece on his previous book The Haves and Have-Nots:

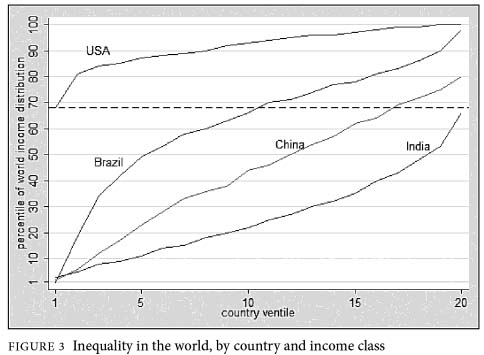

The graph shows inequality within a country, in the context of inequality around the world. It can take a few minutes to get your bearings with this chart, but trust me, it’s worth it.

Here the population of each country is divided into 20 equally-sized income groups, ranked by their household per-capita income. These are called “ventiles,” as you can see on the horizontal axis, and each “ventile” translates to a cluster of five percentiles.

The household income numbers are all converted into international dollars adjusted for equal purchasing power, since the cost of goods varies from country to country. In other words, the chart adjusts for the cost of living in different countries, so we are looking at consistent living standards worldwide.

Now on the vertical axis, you can see where any given ventile from any country falls when compared to the entire population of the world.

Now the clincher:

Now take a look at America.

Notice how the entire line for the United States resides in the top portion of the graph? That’s because the entire country is relatively rich. In fact, America’s bottom ventile is still richer than most of the world: That is, the typical person in the bottom 5 percent of the American income distribution is still richer than 68 percent of the world’s inhabitants.

Now check out the line for India. India’s poorest ventile corresponds with the 4th poorest percentile worldwide. And its richest? The 68th percentile. Yes, that’s right: America’s poorest are, as a group, about as rich as India’s richest.

This goes hand-in-hand with yesterday’s post about GDP per capita (PPP). Should provide some much-needed context when we talk about inequality and “the rich.”

GDP Per Capita: United States vs. Everyone Else

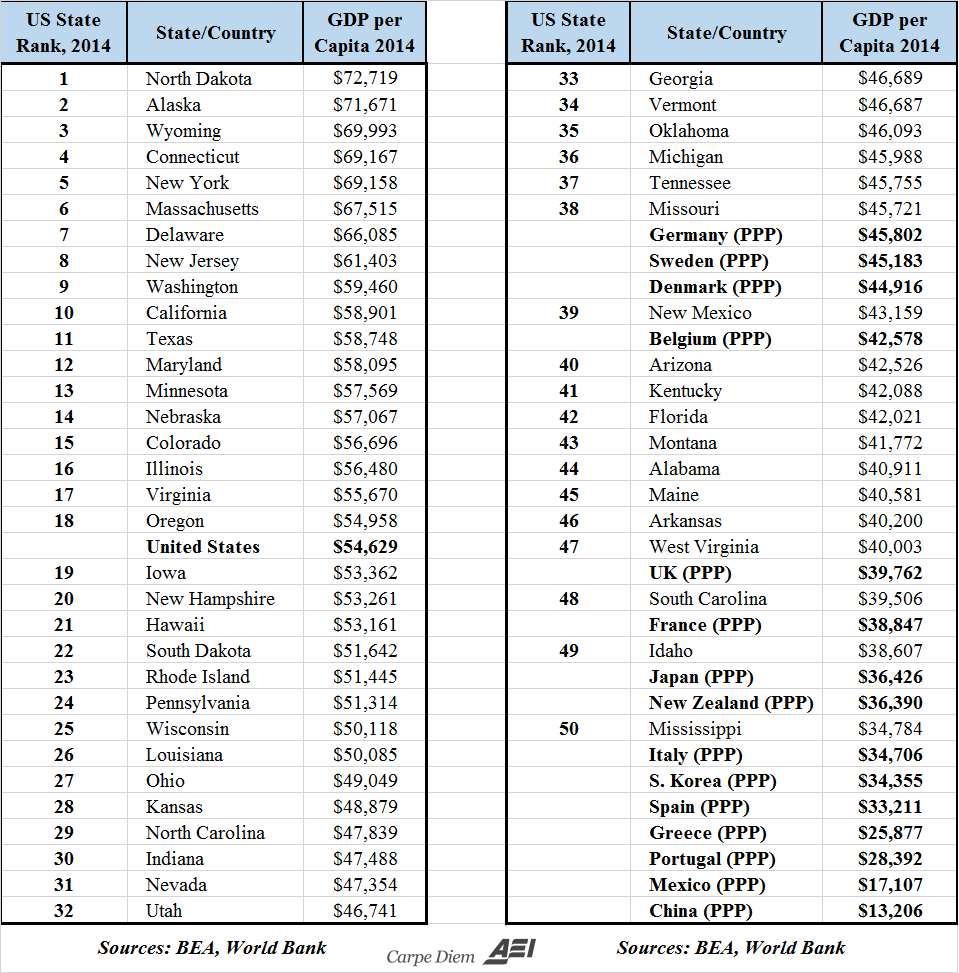

Economist Mark Perry has put together an eye-opening chart based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the World Bank that compares GDP per capita (PPP) in the United States (state-by-state) and other countries, including those of Europe. As Perry explains,

Adjusting for PPP allows us to make a more accurate “apples to apples” comparison of GDP per capita among countries around the world by adjusting for the differences in prices in each country. For example, the UK’s unadjusted GDP per capita was $45,729 in 2014, but because prices there are higher on average than in the US (for food, clothing, energy, transportation, etc.), the PPP adjustment lowers per capita GDP in the UK to below $40,000. On the hand, consumer prices in South Korea are generally lower than in the US, so that increases its GDP per capita from below $28,000 on an unadjusted basis to above $34,000 on a PPP basis.

And what does he find?

“As the chart demonstrates,” Perry writes,

most European countries (including Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Belgium) if they joined the US, would rank among the poorest one-third of US states on a per-capita GDP basis, and the UK, France, Japan and New Zealand would all rank among America’s very poorest states, below No. 47 West Virginia, and not too far above No. 50 Mississippi. Countries like Italy, S. Korea, Spain, Portugal and Greece would each rank below Mississippi as the poorest states in the country.

The Cato Institute’s Daniel Mitchell adds a few more points, including the OECD’s Individual Consumption Index:

He concludes,

None of this suggests that policy in America is ideal (it isn’t) or that European nations are failures (they still rank among the wealthiest places on the planet).

I’m simply making the modest — yet important — argument that Europeans would be more prosperous if the fiscal burden of government wasn’t so onerous. And I’m debunking the argument that we should copy nations such as Denmark by allowing a larger government in the United States (though I do want to copy Danish policies in other areas, which generally are more pro-economic liberty than what we have in America).

Good stuff.

College Is Not the Great Equalizer

That’s one takeaway from a recent post by Brookings fellow Beth Akers:

Essentially, does higher education succeed in lowering intergenerational “stickiness” of socioeconomic status?

Unfortunately, the evidence doesn’t paint as rosy of a picture as we’d like to see. New evidence shows that a college degree might be worth less if you’re raised poor. We can’t say for sure why this is the case, but it’s easy to imagine a number of reasonable explanations. For instance, it’s likely that students who grown up in poorer families attend lower quality institutions. The disparity in returns is so large that individuals who are born into poor families (the lowest quintile of the income distribution) and manage to graduate from college have the same chance of staying in the bottom income quintile as people who are born into rich families (higher income quintile) and don’t complete high school.

Another one is to ignore (or at least temper) the increasingly popular notion that a college education is about knowledge, not a path to higher income:

For a long time we’ve hesitated to talk about education as a financial investment, but that has a done a disservice to the students who can’t really afford the luxury of turning a blind eye to the economic consequences of their decisions. We need to empower students to make good decisions by publishing data on the labor market returns of each program of study covered by the federal student aid program. A large step on this front was taken last year when earnings data for each college was published on a government website. But program level information is also necessary so that students can choose courses of study that are likely to lead them to jobs that will make their college costs worth it.

She adds that we should seek ways to “reduce the risk of investing in higher education including a more robust income driven repayment system in the federal loan program, private market financial products that offer insurance to student borrowers and new business models that offer guarantees to students.”

Check it out.