Now that Donald Trump has wrapped up the GOP nomination, there are two kinds of articles flooding the national conversation:

- Surely this is a sign of the End Times.

- Pundits are dumb!

I can’t really contest #1 because, in a nutshell, I agree.[ref]And yes, I realize my second Tweet is the Platonic ideal of grasping at straws.[/ref]

But let me talk about #2 for a second. First: yes, articles like this one and this one and this one that are full of screenshots of pontifications about how Trump has no chance are funny now that he is the winner of the primary after all. But hold on a second. Does the fact that somebody was wrong about a prediction actually mean that they were dumb? That their prediction was a stupid one? Not necessarily.

If you bet your life savings on being able to flip a coin 5 times in a row and get heads every time, I am going to say you have made a dumb decision. You’ve got about a 97% chance of losing everything and only a 3% chance of winning. But lets say you ignore me, place your bet, and you manage to get lucky and win. This doesn’t make you a genius. It makes you an idiot who got lucky.

People are terrible at statistical reasoning. We like reality simple and we like it deterministic. That means we like to believe that if Y happened, then it’s because of X and obviously X had to cause Y and couldn’t have caused W or Z or coconut soup.

But reality is messy. Sometimes good predictions fail because there was systematic information that nobody had access to. Sometimes good predictions fail because of just plain old dumb luck (like in my example with coin flips). The point is just that even someone who is right 95% of the time is going to get it wrong 5% of the time, and that doesn’t mean that in those 5% of cases where they get it wrong there was actually anything they could or should have predicted differently.

Take a guy like Nate Silver. Unlike your average pundit, he’s got a track record of getting things right by using objective, transparent, quantitative methods. He was largely right in 2008, 2010, and 2012. And this year, he was one of the leading voices telling people to calm down and not worry too much about Trump.[ref]I know, because I was one of the folks who cited him.[/ref] As a result, he is now being singled out by name by, for example, Business Insider: NATE SILVER: ‘We basically got the Republican race wrong’ as one of those silly propeller heads we never should have listened to in the first place.

Not so fast.

First, this is actually a meaningful question. Journalistic credibility is already at historical lows, and that has dire consequences for society. A strong, free press is a bedrock institution of democracy, and if the press is perceived to be hopelessly biased or suborned or just plain old incompetent, that’s bad for our nation. And it matters whether the perception is real or false. In reality, it’s probably a little of both. My read on Nate Silver (who fulfills the role of a journalist even if he doesn’t fit the old, pre-21st century conception) is that he’s an honest guy doing good work. On the other hand, there is a legitimate argument that journalism is fracturing into a thousand click-bait seeking echo chambers. If we, the reading public, don’t discern between episodic mistakes and systematic corruption, then we can’t provide the necessary incentives for the good ship Free Press to right herself.

It’s also meaningful because we need to know what happened with Trump. Yes, obviously Silver (and most everyone else) predicted the wrong outcome. But the question is why were they wrong? Was it incompetence? Was it information nobody had access to? Or did Trump keep getting heads every time he flipped the coin? Almost none of the articles I’ve read address this question. They just assume that if your prediction fails it was a bad prediction. In other words, they are assuming incompetence. And this means we’re likely to draw all the wrong conclusions about what Trump’s victory means.

So–even though he got it wrong–I strongly recommend reading Silver’s take. In it, he raises this important question explicitly:

What’s much harder to say is whether Trump is a one-off — someone who defied the odds because a lot of things broke in his favor and whose success will be hard to repeat — or if he signifies a fundamental change in American politics.

In answer, he notes the three ways his prediction was systematically off:

- Voters are more tribal than I thought.

- GOP is weaker than I thought.

- Media is worse than I thought.

It’s not clear if these are things Silver should have known or if these are new facts that we only know now because of Trump’s victory, but the point is that–because they are systematica rather than merely random–these are new facts that can help us understand and predict the world going forward.[ref]Until they change again, of course.[/ref]

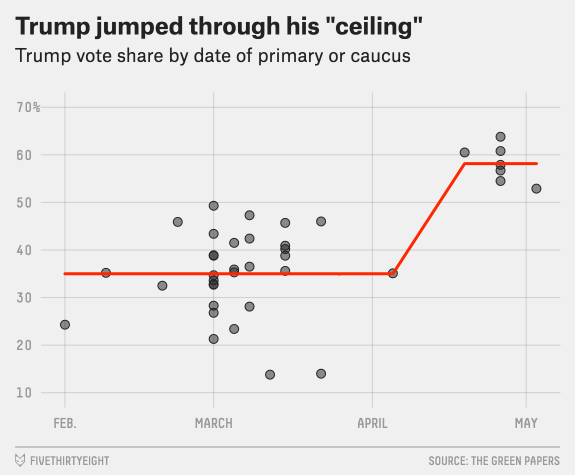

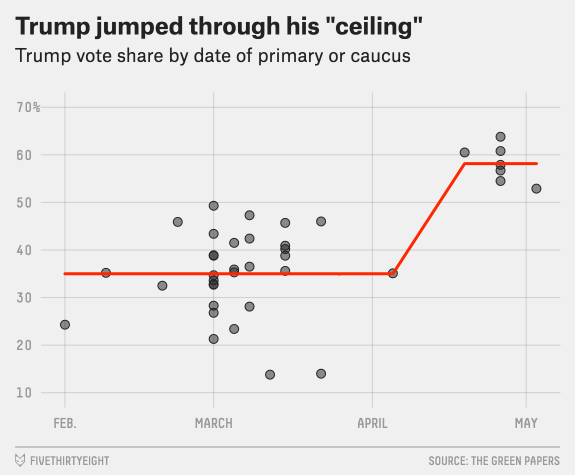

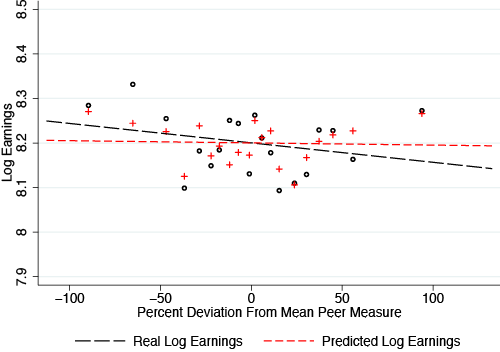

But there is also room for randomness. Take a look at this chart:

Prior to the New York state primary, Trump had never taken a majority in a GOP primary. Since then, he’s never not taken the majority. What happened? Silver’s guess is that voter rationally and deliberately evaluated Trump’s argument that whoever gets the most votes should get the nomination (even if they fall short of a majority) and so decided to make sure Trump got the majority to avoid a contested election. To me, this makes very little sense, because “rationally and deliberately” are not adverbs I usually apply to voter action. And I’m not making a dig at Trump’s voters, I just mean that group action seldom has that kind of rational, deliberate nature without some kind of elaborate infrastructure to support it.[ref]This is where I could make a long tangent on complex systems, spontaneous order, emergence, and the price system, but I won’t. This time.[/ref]

My guess? Well, two of the big stories leading up to New York were Ted Cruz’s statements about “New York values” and his machinations to win delegates without winning elections in Colorado and Maine. So, what do you think happens when a populist demagogue leading a movement of voters who feel bitter, dispossessed, and disenfranchised by a corrupt, elitist system gets to tar his top challenger as a conniving insider using questionable technicalities to steal votes? Oh, and he insulted you, too. Cruz walked face-first into Trump’s zeitgeist, and that–I am guessing–fueled Trump’s unprecedented win in New York state which, in turn, snowballed into his further victories after that.

Who knows if I’m right or not, though, and that’s my point. This is basically the blind luck category. If I’m right, then it took the coincidence of Cruz and Trump being pretty much right where they were leading up to New York in the polls, plus the rules being what they were in Maine and Colorado, etc. You can find explanations for all of that, but at a certain point we’re just making stories up after the fact to explain what is, in reality, an essentially chaotic reality. Or hey, maybe I’m wrong, in which case nobody knows.

Either way, this matters a lot for the big question: is Trump a one-off? Or a sign of the new reality? I don’t know the answer definitively, but I do know the shallow and vapid articles where some pundits make fun of other pundits for not punditting well enough are just a distracting waste of time.

A

A