A few months ago, I posted about a new working paper exploring the origins of WEIRD psychology. A brand new job market paper builds on this research:

Political institutions, ranging from autocratic regimes to inclusive, democratic ones, are widely acknowledged as a critical determinant of economic prosperity (e.g. Acemoglu and Robinson 2012, North, Wallis, and Weingast 2009). They create incentives that foster or inhibit economic growth. Yet, the emergence and global variation of growth-enhancing, inclusive political institutions in which people broadly participate in the governing process and the power of the elite is constrained, are not well understood. Initially, inclusive institutions were largely confined to the West. How and why did those institutions emerge in Europe?

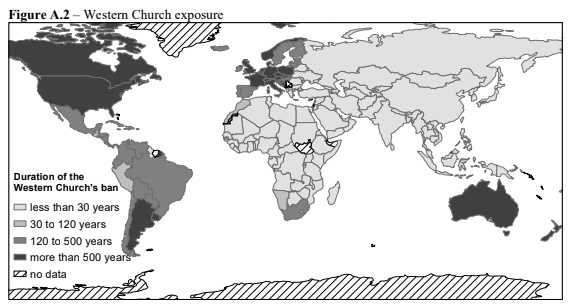

This article contributes to the debate on the formation and global variation of inclusive institutions by combining and empirically testing two long-standing hypotheses. First, anthropologist Jack Goody (1983) hypothesized that, motivated by financial gains, the medieval Catholic Church implemented marriage policies—most prominently, prohibitions on cousin marriage—that destroyed the existing European clan-based kin networks. This created an almost unique European family system where, still today, the nuclear family dominates and marriage among blood relatives is virtually absent. This contrasts with many parts of the world, where first- and second-cousin marriages are common (Bittles and Black 2010). Second, several scholars have hypothesized that strong extended kin networks are detrimental to the formation of social cohesion and affect institutional outcomes (Weber, 1958; Todd, 1987; Augustine, 1998). Theologian Augustine of Hippo (354–430) pointed out that marrying outside the kin group enlarges the range of social relations and “should thereby bind social life more effectively by involving a greater number of people in them” (Augustine of Hippo, 354-430 / 1998, p. 665). More recently, Greif (2005), Greif and Tabellini (2017), Mitterauer (2010), and Henrich (forthcoming) combined these two hypotheses and emphasized the critical role of the Church’s marriage prohibitions for Europe’s institutional development (pg. 2).

His findings?:

The analysis demonstrates that already before the year 1500 AD, Church exposure and its marriage regulations are predictive of the formation of communes—self-governed cities that put constraints on the executive. The difference-in-difference analysis does not reveal pre-trends and results are robust to many specifications. They hold within historic political entities addressing concerns that the relation is driven by other institutional factors and when exploiting quasi-natural experiments where Church exposure was determined by the random outcomes of medieval warfare. Moreover, exploiting regional and temporal variation in marriage regulations suggests that the dissolution of kin networks was decisive for the formation of communes.

The study also empirically establishes a robust link between Church exposure and dissolution of extended kin networks at the country, ethnicity and European regional level. A language-based proxy for cousin marriage—cousin terms—offers a window into the past and rules out that the dissolution was driven by more recent events like the Industrial Revolution or modernization. Moreover, the study reports a robust link between kin networks, civicness and inclusive institutions. The link between kin networks and civicness holds within countries and—getting closer to causality—among children of immigrants, who grew up in the same country but vary in their vertically transmitted preference for cousin marriage. Kin networks predict regional institutional failure within Italy, ethnicities’ local-level democratic traditions and modern-day democratic institutions at the country level. Measures for the strength of pre-industrial kin networks rule out contemporary reverse causality or the possibility that the estimates are driven by contemporary omitted variables. The analysis also demonstrates that the association between kin networks and the formation of inclusive institutions holds universally—both within Europe and when excluding Europe and countries with a large European ancestry. This universal link strengthens the hypothesis that the Church’s marriage regulations, and not some other Church-related factor, were decisive for European development.

Underlying these early institutional developments was most likely a psychology that, as a consequence of dissolved kin networks, reflects greater individualism and a more generalized, impartial morality (Schulz et al. 2018). This is a building block not only for inclusive institutions but also for economic development more generally. For example, transmission of knowledge across kin networks and the shift away from a collectivistic culture toward an individualistic one, a culture of growth, may have further contributed to Europe’s economic development (Mokyr, 2016; de la Croix, 2018).

…To build strong, functional, inclusive institutions and to foster democracy, the potentially deleterious effect of dense kin networks must be considered. Also, simply exporting established formal institutions to other societies without considering existing kin networks will likely fail. Policies that foster cooperation beyond the boundaries of one’s kin group, however, have a strong potential to successfully diminish the fractionalization of societies. These can be policies that encouraging marriages across kin groups. More generally, policies that foster interactions that go beyond the boundaries of in-groups such as family, close friends, social class, political affiliation or ethnicity are likely to increase social cohesion (pg. 41-42).